You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce

Doubts about the labor-market returns of bachelor’s degrees, while never serious, can be put to rest.

Last month’s federal jobs report showed a rock-bottom unemployment rate of 2.8 percent for workers who hold at least a four-year degree. The overall unemployment rate is 5.7 percent.

But even that welcome economic news comes with wrinkles. A prominent financial analyst last week signaled an alarm that employers soon may face a shortage of job-seeking college graduates. And the employment report was a reminder of continuing worries about “upcredentialing” by employers, who are imposing new degree requirements on jobs.

“Presumably, these educated workers are the most productive in our information economy,” wrote Guy LeBas, a financial analyst with Janney Montgomery Scott, in a report Bloomberg Business and other media outlets cited. “At some point in the coming year, we’re going to risk running out of new, productive people to employ.”

Anthony P. Carnevale concurred with LeBas. As director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce and a top expert on the labor-market returns of degrees, Carnevale has long railed against dubious arguments about the payoff from college being overrated.

“We’re headed for full employment” of bachelor’s-degree-holding workers, he said.

It’s a challenge decades in the making. Carnevale cites research that has found colleges lagging badly in producing talent. Since 1983, the job market has outpaced higher education with a cumulative total of 11 million positions for workers with “usable knowledge,” which he defines as “degrees with labor-market value.”

These days, demand for positions in the knowledge economy grows by 3 percent each year, Carnevale said, while higher education meets only 1 percent of that growth.

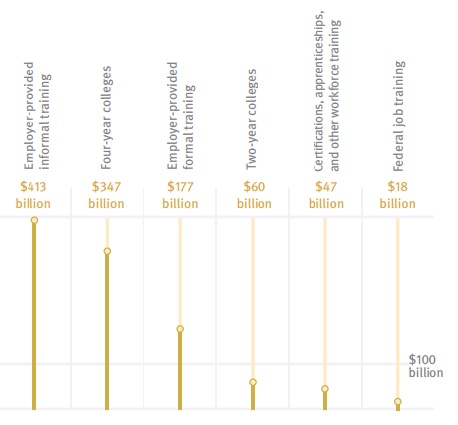

That’s where employers step in. Carnevale’s center last week released a report that broke down the $1.1 trillion colleges, government agencies and employers spend each year on higher education and job training in the United States. Employers chip in the most, the report found, spending $590 billion annually to train workers.

Of that amount, $413 billion paid for informal, on-the-job training. Colleges spent $407 billion on formal training, while employers spent $177 billion. However, the academy’s rate of spending has outpaced that of employers, increasing by 82 percent since 1994 compared to 26 percent.

The report, dubbed “College Is Just the Beginning,” also found that four-year-college graduates receive the most of the formal, employer-sponsored job training. Bachelor’s degree holders account for 58 percent of employers’ annual spending on formal training.

That fact, while somewhat counterintuitive, is because four-year-college graduates tend to get jobs that are specialized, complex and change over time, Carnevale said, particularly in STEM fields.

“Wherever the earnings are the strongest, that’s where the training occurs,” he said. “The more educated the workforce, the more training in the job.”

Workers with an associate degree or some college credit but no degree received 25 percent of formal employer training. Those with a high school credential or less received 17 percent.

'Credential Creep'

The report’s findings strongly suggest that a bachelor’s degree often is required as a starting point for a job that requires more training -- and one that pays well. So dropping out to go work for a tech company isn’t a safe bet for most students.

“Formal employer-provided training typically complements, rather than substitutes for, a traditional college education,” the report said.

The new federal jobs report in some ways bolsters the findings from a study released last fall by Burning Glass Technologies, a Boston-based employment firm that analyzes job advertisements. That research found that employers are more likely to replace workers who do not have bachelor’s degrees with those who do.

One reason for this, according to Burning Glass, is that many “middle skills” jobs are becoming more technological and complex. Architectural drafters, for example, these days are expected to be “junior engineers,” the report found.

But employers also appear to be screening applicants by requiring bachelor’s degrees for positions that do not require nor are likely to require the kind of training one would get from a B.A. or B.S., according to the report, citing certain human resources and clerical jobs as examples.

This sort of credential creep is alarming to some economists, such as Richard Vedder, who directs the Center for College Affordability and Productivity and teaches economics at Ohio University. Vedder has written that an oversupply of bachelor’s degrees creates its own demand.

Wage Gains

The virtually nonexistent unemployment rate for bachelor’s holders poses a test to higher education, Carnevale said, beyond just trying to keep up with employer demand.

That’s because the “wage premium” for workers with a four-year degree relative to those who hold only a high-school credential, while large, has stagnated in recent years. As employers run out of graduates to hire, however, the wage premium should climb again. That outcome would be further proof of the value of a four-year degree.

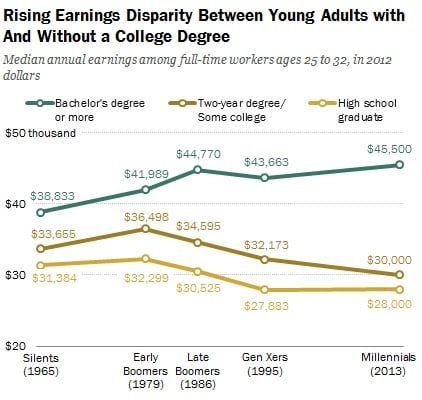

Full-time workers with a bachelor’s degree or more who are between the ages of 25 and 32 have median annual earnings of $45,500, according to a report the Pew Research Center released last year. Two-year-degree holders or those with some college credits and no degree earn $30,000 while high school graduates earn $28,000.

Another study, which the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco released last year, tracked the fluctuating earnings premium for a four-year degree.

The premium was at its lowest in 1980, when bachelor’s degree holders earned 43 percent more, on average, than workers with just a high school credential. In 2011, however, it was 61 percent, or $20,050 per year.

.jpg)

Carnevale predicted that gap would widen because of the high demand for bachelor’s degree holders. But it will take about two years for those effects to show, he said.

LeBas agreed that earnings gains of highly educated employees will outpace others. “Wage pressures among skilled workers will almost certainly rise further in the coming year,” he wrote.