You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Like their peers across the country, Virginia public institutions have responded to state funding reductions in recent years by raising tuition.

A new analysis released Wednesday shows, in stark detail, how those increased costs to students are impairing the success of students in the state, particularly low-income students.

“Rising costs have deterred students from remaining in college and completing their degrees, and the lowest-income students have been hit the hardest,” write the authors of the study, which was prepared by the research firm Ithaka S+R in collaboration with the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia. It was funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

The study is unusual in that it tracked enrollment patterns and degree completion of students at the individual level. Researchers studied the data of more than 1.4 million students who enrolled in public colleges in Virginia between 1997 and 2013.

Over that time period, particularly during the Great Recession, Virginia's public universities were forced to rely more heavily on tuition and student charges as state lawmakers slashed money for higher education.

Students, of course, ended up paying more for higher education in the state. But the net cost of attending college for low-income students grew the fastest, the new study shows.

Not only that, but those rising costs harmed the disadvantaged students’ success rates the most.

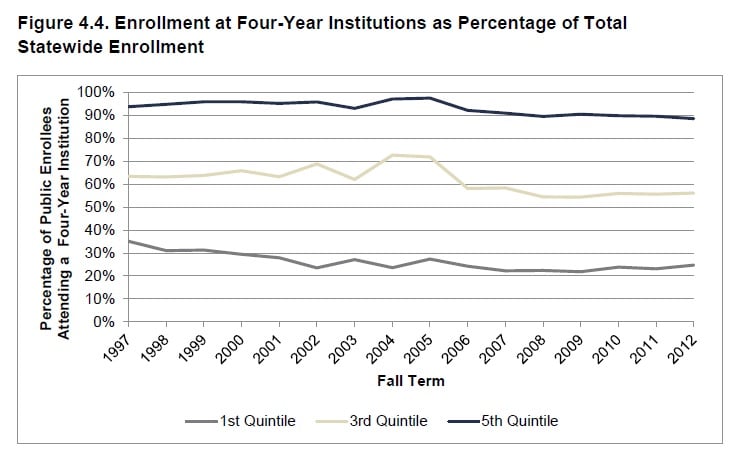

The analysis shows large disparities between low-income students and their wealthier peers in where they enrolled in public college in Virginia. Less than a quarter of the lowest-income students in the state who went to a public college or university went to a four-year institution. Meanwhile, 90 percent of their wealthier peers enrolled at a four-year university.

Further, the study found, since 2007 the state had made no progress in improving the socioeconomic diversity of its four-year institutions; the large gap in enrollment between poor and wealthy students has remained virtually unchanged.

Students from low-income families who attend four-year universities were less likely “to remain enrolled, persist through and graduate from those institutions,” compared to students from more affluent families.

The study outlines a number of policy recommendations. Aside from increasing state funding of higher education and more efficiently running those institutions, the report calls for a performance-based funding approach to allocating state dollars to universities.

It recommends greater investment in community colleges with “an important caveat” that completion rates for most such institutions “are so low that investing more funds without significantly improving performance at those institutions would have a limited impact on educational levels over all.”

The state and institutions should also, the report suggests, allocate more money to need-based financial aid, to protect low- and middle-income families from bearing the brunt of increasing tuition costs.