You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Demos

Public university students today pay $3,000 more in annual tuition than their counterparts a decade ago.

Why that is depends on whom you ask. Some pundits like to blame administrative bloat or the construction boom. Within higher education, many cite the decline in state support.

“Although academics and media alike have tried to put the question to rest, public confusion on this issue is one reason why effective solutions remain illusory in almost every state,” asserts a report released today by Demos, a left-leaning New York public policy think tank.

The report attempts to pinpoint the factors driving up the price for students seeking a four-year degree at a public college. It asserts that while rising administrative and construction costs are a factor, they’re not as gargantuan as widely believed. A decline in state funding is the real culprit, says author Robbie Hiltonsmith, a senior policy analyst with Demos.

“That is really the real story here. The magnitude of [state funding declines] is so much larger than the magnitude of all these other things,” Hiltonsmith said.

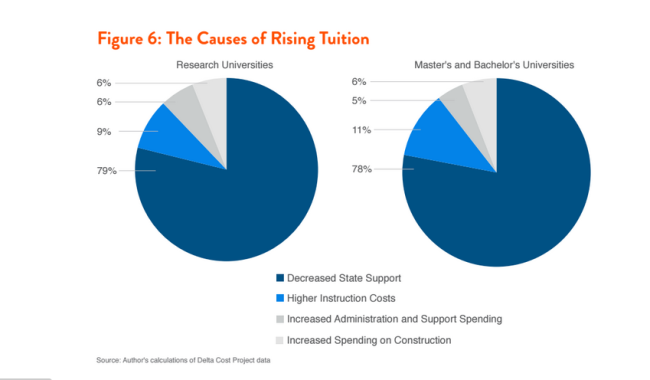

Demos derived much of its data for the report from the Delta Cost Project, which studies how colleges spend their money. The report analyzed research institutions -- universities that conduct high-level research, award a large number of doctorates and confer about 60 percent of public undergraduate degrees -- separately from institutions that primarily award bachelor’s and master's degrees.

Per-student spending at research institutions, according to the report, rose 8 percent from 2001 to 2011 (the uptick was 1 percent at nonresearch colleges).

Demos estimated that during this period, between 78 and 79 percent of the tuition hikes at public universities -- which averaged $3,628 per student at research universities and $2,463 per student at nonresearch colleges -- was due to declining state appropriations, between 5 and 6 percent was due to increased administrative spending, and another 6 percent was due to construction costs.

“Spending increases pale in comparison to tuition increases,” the report says, but it cautions against looking at administrators and new facility construction as the reason.

Administrative Bloat?

“The relative number of full-time faculty has remained approximately constant and the number of executives and administrators has actually slightly decreased relative to the size of the student body,” the report said. The number of clerical, maintenance and skilled-trade workers has also decreased.

Instead, public colleges are employing “substantially more” part-time faculty and professional staff, such as employees who work in admissions, human resources, information technology and athletic departments.

“A lot of these people are necessary. For every second assistant dean that people complain about, there's also an additional counselor or an additional financial aid person or an additional IT person. And all of these things are necessary to support the growing university,” Hiltonsmith said. “There aren't a lot of efficiencies to be made -- this does need to increase proportionally.”

The Demos findings come at a time, however, when many people continue to focus on administrate bloat as a key issue behind rising tuition.

“A major factor driving increasing costs is the constant expansion of university administration,” University of Colorado law professor Paul Campos wrote in a New York Times essay last month. Campos cited Department of Education data that show the number of administrative positions at colleges grew 60 percent from 1993 to 2009. “The explosion in administrative personnel is, at least in theory, defensible. On the other hand, there are no valid arguments to support the recent trend toward seven-figure salaries for high-ranking university administrators.” (Many, including an Inside Higher Ed blogger, have published rebuttals of Campos's essay.)

Part of the reason for an uptick in personnel spending, the Demos report states, is because colleges are spending more on benefits per employee. Health care costs rose about 40 percent from 2001 to 2011.

Spending on auxiliary developments, such as dormitories, rose $1,789 per student at research institutions and $524 per student at nonresearch colleges. Yet while spending is up, revenue from auxiliary developments -- such a room and board charges or donations -- is rising at an even faster rate, the report found. In 2011, revenue from auxiliary enterprises exceeded spending.

Grant and loan aid -- which some have credited with pushing tuition up -- have had a “negligible effect” at both types of institutions, the report states.

“Dramatic” Funding Shift

During the 2001 to 2011 time period, state funding per student fell $3,081 at research universities and $2,067 at nonresearch universities, a decline that was “in near lockstep with tuition increases,” according to the report. The result is a “dramatic shift” in who is paying for the cost of a public education.

As states divest in public higher ed, Hiltonsmith says colleges can either cut expenses or raise tuition to make up for the lost revenue.

“If there isn't a lot of fat to cut, then their only option is to raise tuition or lose quality of education,” he said.

More than half of core educational expenses at public four-year universities are now funded through tuition. In 2011, 57 percent of tuition at research universities -- and 52 percent at nonresearch colleges -- was derived from tuition, according to the report. A decade earlier, those figures were at 34 percent and 36 percent respectively.

Figures from the Demos report are higher than comparable figures from a recent report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers, which found that tuition dollars made up roughly 47 percent of revenues for public higher education from 2012 to 2014.