You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Competing for European Research Council grants is often likened to entering European football’s Champions League, with success seen as the ultimate affirmation of excellence. But while the likes of Chelsea and Manchester United have underachieved in recent years in the Champions League, British researchers have been running away with trophy after trophy since the ERC was established in 2007.

The success rate in the latest round of the ERC’s advanced grants, aimed at senior research leaders, was just 8.3 percent, compared with 23 percent for Britain's most competitive research council, the Medical Research Council, in 2013-14. This reflects the fact that the program -- which received 2,287 applications -- was open to researchers from all 28 European Union members, plus another four “associated countries.”

The success rate in the latest round of the ERC’s advanced grants, aimed at senior research leaders, was just 8.3 percent, compared with 23 percent for Britain's most competitive research council, the Medical Research Council, in 2013-14. This reflects the fact that the program -- which received 2,287 applications -- was open to researchers from all 28 European Union members, plus another four “associated countries.”

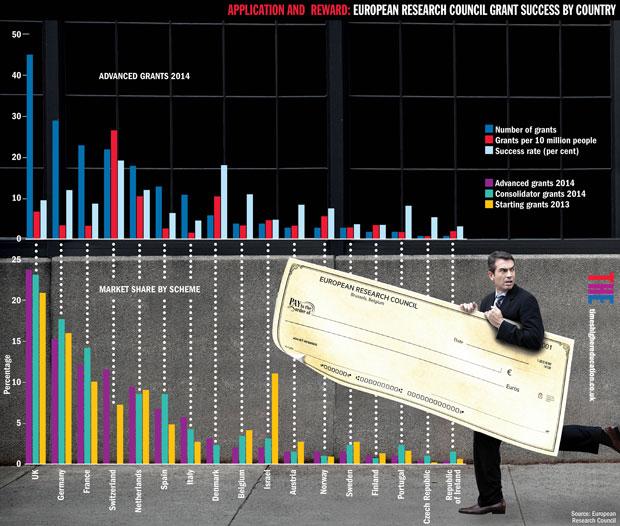

Despite the crowded field, U.K.-based researchers secured 45 of the 190 grants awarded, for a market share of 23.7 percent (see graph, below). This is an improvement on the U.K.’s tally of 22.9 percent of the 284 grants given out in the last round of advanced grants in 2013 (when the overall success rate was 11.8 percent) and is 8.4 percentage points higher than the next most successful nation, Germany.

However, the U.K. arguably should be doing even better, given that it made nearly twice as many applications as its closest rival, submitting 466 against Germany’s 239. It also submitted more than 200 applications more than the second most prolific applicant, France -- possibly reflecting the enormous pressure British researchers are under to bring in grant income. The U.K.’s success rate, 9.7 percent, was less than that of Belgium (11.1 percent), Germany (12.1), the Netherlands (12.2), Denmark (18.2) and Switzerland (19.3).

Switzerland was also by far the most successful country in terms of grants won per head of population. Its 26.6 grants per 10 million people compares with 10.6 for Denmark and the Netherlands and 6.9 for the U.K. (Germany was eighth, with 3.6, and France 11th with 3.5).

Switzerland’s success is particularly noteworthy given that it nearly did not make it into the program at all. Negotiations for associated membership of the E.U.’s overarching Horizon 2020 research program were suspended early last year after the Swiss voted in a referendum to impose quotas on immigration. The impasse was finally resolved, as regards participation in ERC programs, last September.

The Swiss share of the total number of grants awarded has risen from 9.2 percent in 2013 to 11.6 percent in 2014. Other countries that have improved their market share include Germany (up from 14.4 to 15.3 percent), Spain (4.6 to 6.8 percent) and Denmark (1.8 to 3.2 percent). By contrast, Israel’s market share has slipped from 6 to 2.1 percent, with a success rate of just 4.9 percent. However, measured by head of population, Israel -- another associated member -- remains the sixth most successful country, with 4.8 grants per 10 million people.

Israel has been even more successful in other recent ERC funding rounds. It won 3.2 percent of the 372 consolidator grants awarded earlier this year, aimed at midcareer researchers, putting it third by head of population -- topped only by the Netherlands and Denmark. The U.K. was fourth, and again secured the largest market share: 23.1 percent of the total. But its lead over Germany and France, which had shares of 17.7 percent and 14.2 percent respectively, was smaller than for advanced grants.

Israel did even better in last year’s most recent round of starting grants, aimed at researchers within seven years of their Ph.D. The 32 grants it won amounted to 11.1 percent of the total, and 38.6 per 10 million people. Switzerland was the next most successful country on the latter measure, with 25.4 grants per 10 million people, followed by the Netherlands (15.4), Belgium (10.7), Austria (9.3) and the U.K. (9.2).

The U.K. again took the lion’s share of these grants, but its market share of 20.9 percent was the lowest of the three programs, and its lead over Germany, which took 16 percent, was the narrowest. Switzerland’s 7.3 percent market share was also markedly lower than for advanced grants (last year’s impasse meant that it could not apply for the most recent round of consolidator grants). However, this does not necessarily presage any future decline in the two countries’ success in the advanced grant competition -- provided they keep their borders open. The latest advanced grant figures reveal that more than half of Switzerland’s grant winners and about a third of the U.K.’s have come to the countries from elsewhere; only nine of Switzerland’s 22 grant winners and 31 of the U.K.’s 47 were nationals of the respective countries.

Some E.U. members from the east of the continent, such as Bulgaria, Lithuania and Latvia, won no grants in any of the three schemes’ most recent rounds. Turkey, the second largest of the competing countries by population, won just one, as did Poland and Romania, the seventh and eighth most populous respectively.

However, Latvia did not submit a single application to the latest advanced grant round, and only Poland, with 33, submitted more than 20 applications. The country that submitted the most applications without any success was Greece, with 41. But that, presumably, is the least of its worries at the moment.