You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

New York-Presbyterian Hospital

NASHVILLE, Tenn. -- In an era of increasing scrutiny and growing financial difficulty, health care and higher education face many of the same challenges: disruption, rising prices, consumer criticism, decreasing public funds and an increasing need for collaborations and mergers.

“There’s a huge amount of discussion in health care around quality,” said Emme Deland, senior vice president for strategy at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, during the National Association of College and University Business Officers' annual meeting here.

“So I was thrilled to find that you're being asked the … question ‘Is college worth it?’ It’s the same question that’s being asked of health care: What’s the value that we’re actually delivering?”

That’s a cogent question, Deland says, highlighting how when she received her M.B.A. from Columbia University in the late 1970s, the cost was about $4,000 a year. Her daughter recently entered the business school and the cost is exponentially more, at $60,000 a year.

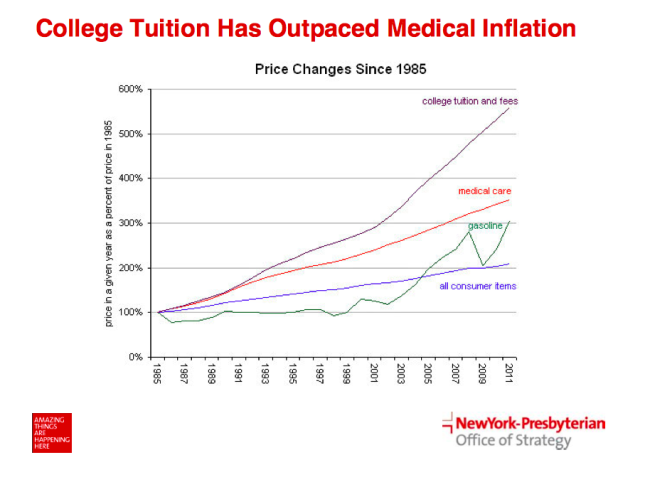

She cited statistics from her strategy office that show the price of tuition and fees, on average, grew over 550 percent from 1985 to 2011 -- easily outpacing the roughly 350 percent rise in the price of health care during that time.

“We’re doing a really good job of increasing our charges faster than any other industry,” Deland said of higher education and health care.

Meanwhile, she acknowledged the massive enterprise of health care spending, including criticisms of wasteful spending. Health care is a roughly $2.9 trillion annual industry in the U.S., and some estimate that as much as $750 billion is being spent wastefully each year.

The rising price of health care and higher education, and cost of delivery, are far from the only things the two sectors have in common.

Both are learning how to live with less public money.

Just as state appropriations in public higher education have declined in recent decades, the Affordable Care Act is translating into less federal money for hospitals and health care systems. Deland estimates that New York-Presbyterian is poised to lose at least $1.5 billion in federal dollars over the next five years because of changes resulting from the ACA.

Meanwhile, both industries are being disrupted by new technologies -- especially online delivery systems. In higher education, that in part means MOOCs and online and interactive components to traditional courses (Deland said three of her friends have forgone graduate courses for MOOCs instead).

In health care, hospitals and systems are exploring teleheath delivery systems in which patients receive maintenance care, follow-up appointments and medical information through telecommunication devices like computers and smartphones. The practice has the power, according to Deland, to “truly revolutionize the delivery system of health care” and create much more consumer-friendly care.

Hospitals and health systems have also been merging and acquiring one another with increasing frequency. Deland said that in recent decades New York City went from having about 75 independent hospitals to six hospital systems.

And while the scale and scope of mergers in higher education is much smaller, universities and colleges are having to find more ways to work together and create efficiencies as they try to trim costs.

For both industries, adjusting to new challenges has been an uphill climb.

The NACUBO conference is titled “The Tempo of Change,” in part because colleges and universities are grappling with how to adapt to an era of financial difficulty and increased scrutiny and in part as a play on Nashville's nickname, Music City.

Health care is learning to adapt to a similar reality, Deland said.

“In health care, that tempo has accelerated to almost epic proportions,” she offered, adding later: “Academic medical centers are profoundly good at sticking our heads in the sand because ‘we’re different, we’re special.’”

But in order to thrive in ever-changing environments, hospitals and universities have to tackle challenges with their eyes wide open.

“This is not a short road,” Deland readily admits.