You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A succession of bibliometric studies carried out in recent years suggest that international collaboration has a significant positive effect on the quality of research.

For instance, Elsevier’s report “International Comparative Performance of the UK Research Base -- 2011,” carried out for the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, reveals that the 46 percent of British academics who published with overseas collaborators in 2010 garnered twice as many citations for their papers as those who collaborated only within their institution. They also had 40 percent more citations than those who collaborated with academics at other institutions in the U.K.

But why is the U.K. so internationally collaborative? According to the 2013 edition of Elsevier’s annual report, the key reason is that researchers in the U.K. are highly internationally mobile.

But why is the U.K. so internationally collaborative? According to the 2013 edition of Elsevier’s annual report, the key reason is that researchers in the U.K. are highly internationally mobile.

“International research collaboration and international researcher mobility can be considered as two sides of the same coin, representing collaborative interactions with or without physical co-location,” it says.

Times Higher Education asked Elsevier, the citation data provider for Times Higher Education's World University Rankings, to look at researcher mobility levels globally, to find out which other countries benefit from the mobility premium -- or suffer from its absence.

Elsevier examined the institutional addresses listed on papers in the Scopus database. Where researchers have had addresses in different countries, they are counted as being mobile -- although analysis is confined to authors who have published at least one article in the past five years and at least 10 articles since 1996, or those with at least five papers in the past five years.

Swiss Top the Travel Table

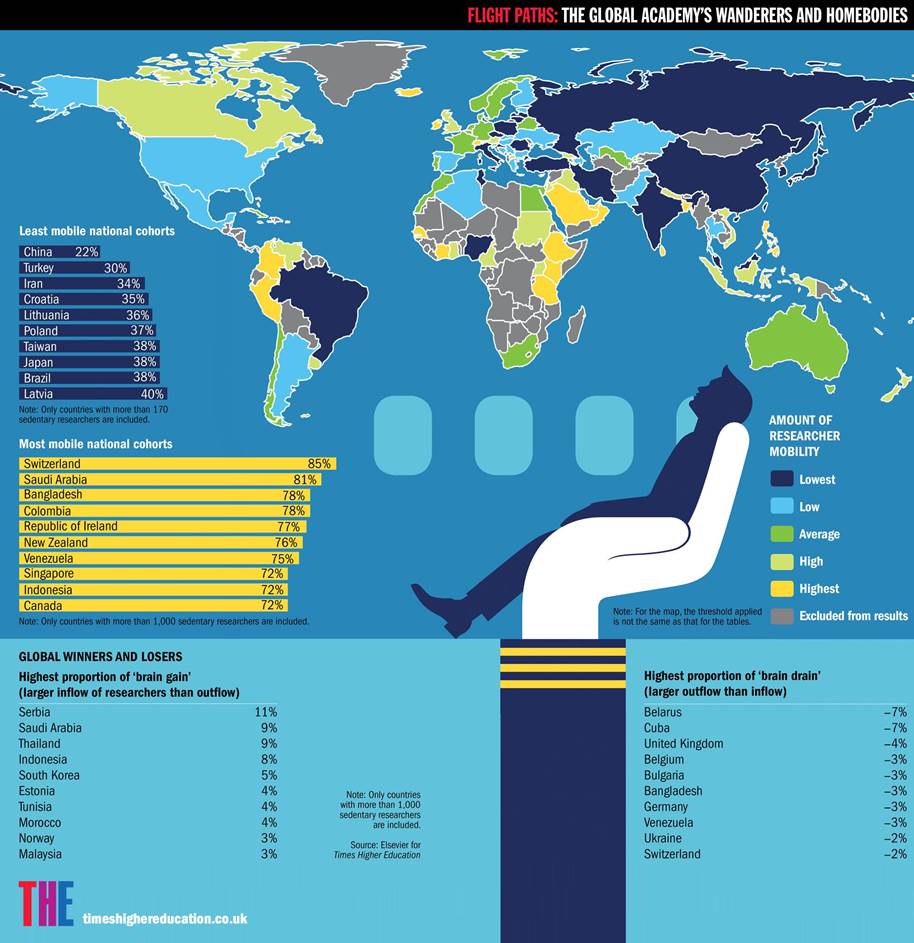

The analysis reveals that 71 percent of U.K. researchers are internationally mobile. But this places the country only 11th in the ranking. The nation with the greatest proportion of internationally mobile researchers (see chart, below) is Switzerland, with 85 percent. Second is Saudi Arabia (81 percent), and Bangladesh is third (78 percent). The top 10 also includes other developing countries (Colombia, Venezuela and Indonesia) interspersed with the likes of the Republic of Ireland, New Zealand and Canada.

The reason for this strange mixed bag is that the analysis does not distinguish between inward and outward movement, and is unable to identify the nationality of movers.

Judith Kamalski, head of analytical services in research management at Elsevier, surmised that the high level of mobility in many developing countries reflected high outflow levels due to “inadequate research infrastructure, low [native] production of Ph.D.s, and shortages in funding.” Additionally, these countries “play a very small role in [world] science, and within the small research community in these countries there is little interest in staying.”

The Global Academy’s Wanderers and Homebodies

The ranking excludes countries with very small numbers of researchers, but Kamalski added that many countries with small researcher populations show high levels of mobility. “For instance, of the 142 active researchers in Afghanistan, only five have never published with an affiliation outside of Afghanistan,” she said.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the country with the least internationally mobile researchers is China. The other BRIC nations, Brazil, Russia and India, are also present in the top 14 most “sedentary” nations. Kamalski noted that in China, sedentary researchers have on average a “field-weighted citation impact” of 25 percent below the world average. By contrast, researchers moving into China have a citation impact 24 percent above world average, and the ones who leave China score 46 percent above the world average.

“Either mobility increases citation impact, or researchers with a higher citation impact are more likely to move internationally. The two factors are clearly linked. Therefore, high percentages of sedentary researchers are in general not beneficial to a country’s citation impact,” Kamalski said.

Another aspect of her analysis looks at the differences between the numbers of researchers entering and leaving different countries. The nation with the highest “brain gain” is Serbia, followed by Saudi Arabia and Thailand. The largest brain drains are suffered by Belarus, Cuba and, surprisingly, the U.K. -- which loses 4 percent more researchers than it gains. Germany and Switzerland are also in the top 10 for brain drain.

But Kamalski said that this was not because Britain's inflow of researchers is low but because its outflow is topped only by that of Switzerland, New Zealand and Singapore. And such high outflows are “not necessarily” a bad thing. “Researchers spend time in the U.K. to gain knowledge and experience, and leave to take this knowledge with them to other countries,” Kamalski said. “This could very well be beneficial for U.K. researchers’ networks and subsequent research, done in collaboration [with those who have left].”

Click graphic to expand.