You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

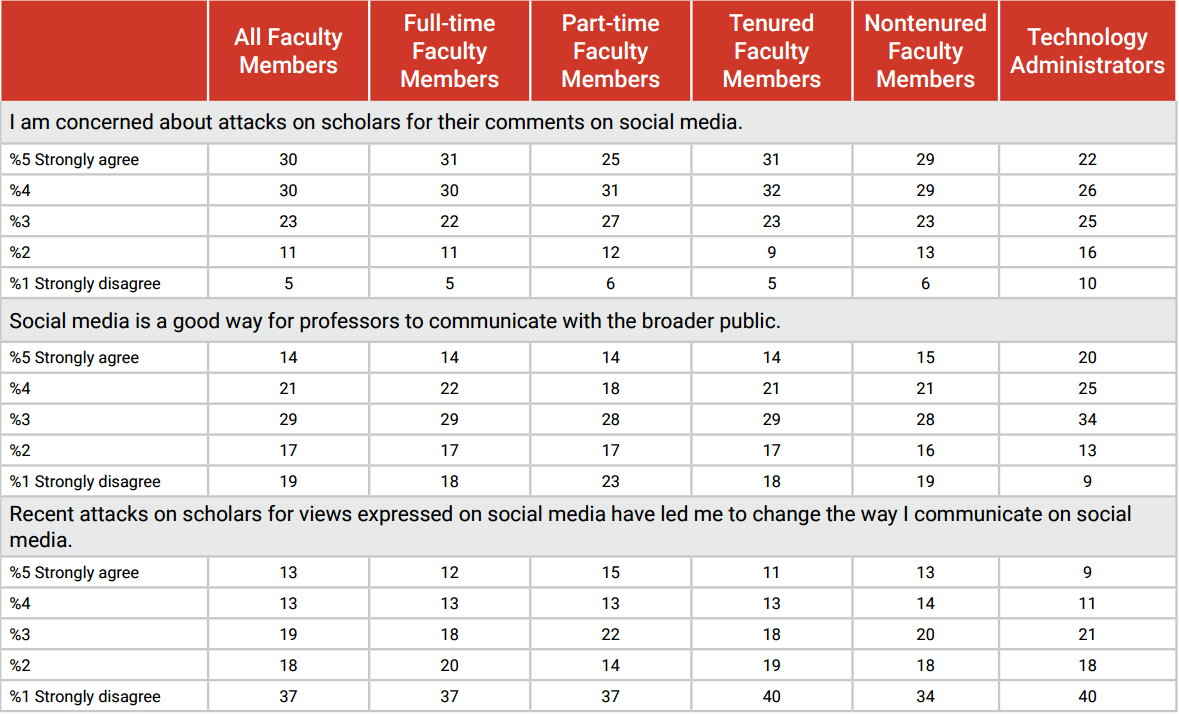

A majority of faculty members say they are concerned about attacks on scholars for their comments on social media, even though only a small percentage of faculty members use social media to discuss politics and scholarship. At the same time, faculty members say colleges need to do more to encourage civil discourse online.

The 2015 Inside Higher Ed Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology, available today, provides a snapshot of how faculty members feel about social media and how it relates to their professional and personal lives. In addition to those topics, researchers from Gallup also surveyed 2,175 faculty members and 105 technology administrators on their views on online education, textbook costs and more.

During the past year in social media controversies, some scholars have found themselves under attack by far-right bloggers. Others have been criticized by university leaders for their behavior. All the while, the twists and turns of the Steven Salaita case have kept the issue front and center.

With these and other cases in mind, 60 percent of surveyed faculty members say they are worried about how scholars have come under attack on social media. Administrators share some of their concern: 48 percent, a plurality, say the same.

Hank Reichman, chair of the American Association of University Professors Committee A on Academic Freedom, Tenure and Governance, said the findings suggest the attacks “represent a serious threat to academic freedom” and that academe needs to fight back.

“Taken as a whole, the survey re-emphasizes the AAUP's call … for institutions to work with their faculty to develop policies governing use of social media that protect the rights of faculty members to address the larger community with regard to any matter of social, political, economic or other interest, without institutional discipline or restraint,” Reichman said in an email.

Faculty members and administrators are split on whether institutions are doing enough to promote civil discourse online. Among faculty members, 55 percent say yes, though only 47 percent of administrators do. About three-quarters of both groups (75 percent of faculty members, 73 percent of administrators) say colleges can do more.

The report also presents a reminder that for all the hundreds of millions of people and organizations active on social media and the perceived importance of news going viral or “blowing up” on Twitter, billions of voices are not present on the platforms. The same phenomenon can be seen on a smaller scale in academe: 75 percent of faculty respondents say they don’t use social media to express their views on scholarship or politics. Only 14 percent of respondents use social media for both, the remainder split between one or the other.

Faculty members are still undecided about whether social media is worth their time. About one-third of respondents (35 percent) say Facebook, Twitter and other platforms are useful for communicating with the broader public, but another third (36 percent) disagrees.

In any case, many faculty members are now second-guessing what they post online. One-quarter of faculty members (26 percent) say the recent attacks have led them to change how they communicate on social media.

“That more than a quarter of the faculty responding say that such attacks have led them to change how they communicate on social media … suggests not only that such attacks have been effective but that they may well discourage some to speak out in any media,” Reichman, also professor emeritus of history at California State University at East Bay, wrote.

But faculty members and administrators need not look farther than their own campuses for social media controversies. Yik Yak, the popular smartphone app that bills itself as a digital “local bulletin board,” has been at the center of several such incidents, including anonymous racist posts and death threats.

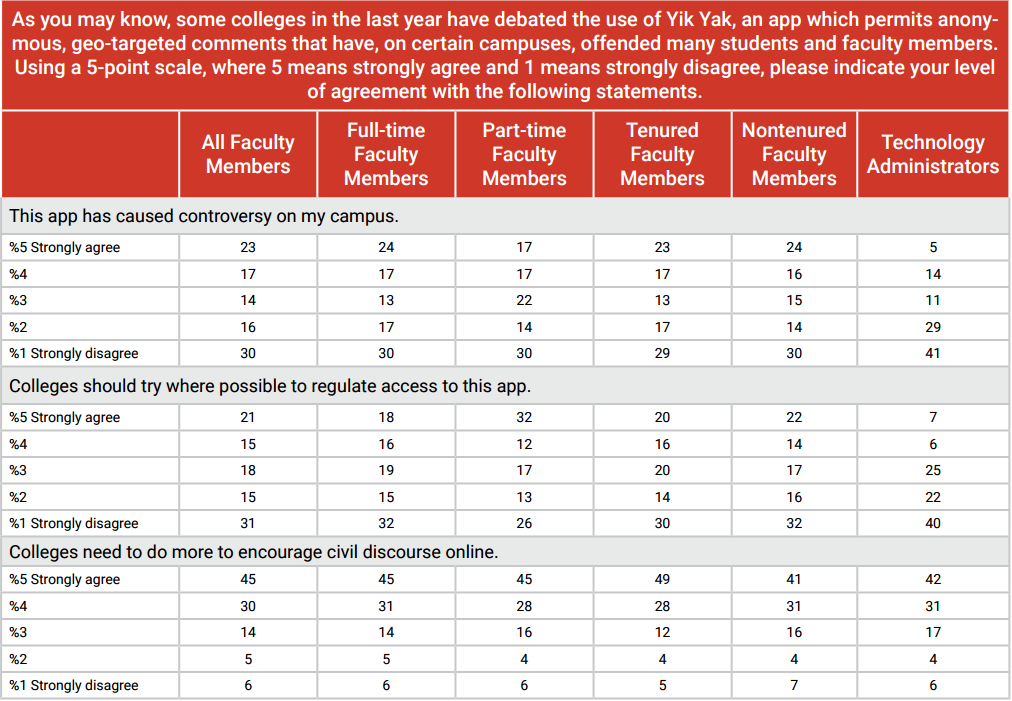

Two out of five faculty members say Yik Yak has been a source of controversy on their campus, and about one-third (36 percent) say colleges should try to regulate access to the app. Administrators don’t see Yik Yak as much of an issue, however. Only 19 percent of those surveyed say Yik Yak has caused trouble on campus, and 13 percent support limiting access to it.

Few institutions have sought to regulate access to Yik Yak, according to the survey. Most faculty members and administrators (91 percent and 95 percent, respectively) say their campus has not attempted to do so. Augustana College is one of only a handful that have barred access.

Some institutions have attempted more creative responses. At Colgate University, the site of one Yik Yak controversy, faculty members last December flooded Yik Yak with positive messages.

“The Venn diagram of free speech, academic freedom and civility is most certainly a complicated space that even some faculty and administrators are finding difficult to navigate,” Douglas Johnson, director of Colgate’s Center for Learning, Teaching and Research, said in an email. “The problem is not any one app, nor technology in general, but instead the issue how we promote civil discourse on a diversity of thoughts and opinions regarding topics that have considerable emotion attached.”