You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Morris Brown College is old and mostly empty. Founded in 1881, it is one of the few historically black colleges started by African-Americans rather than white philanthropists. "Morris Brown came to be an institution noted for providing college access to the children of families with lesser means," notes the photographer of a new book on the institution. "By the turn of the millennium, its campus encompassed over 37 acres and over a dozen buildings; its student body numbered more than 2,000; its sports programs and marching band were legend; its alumni were fiercely loyal."

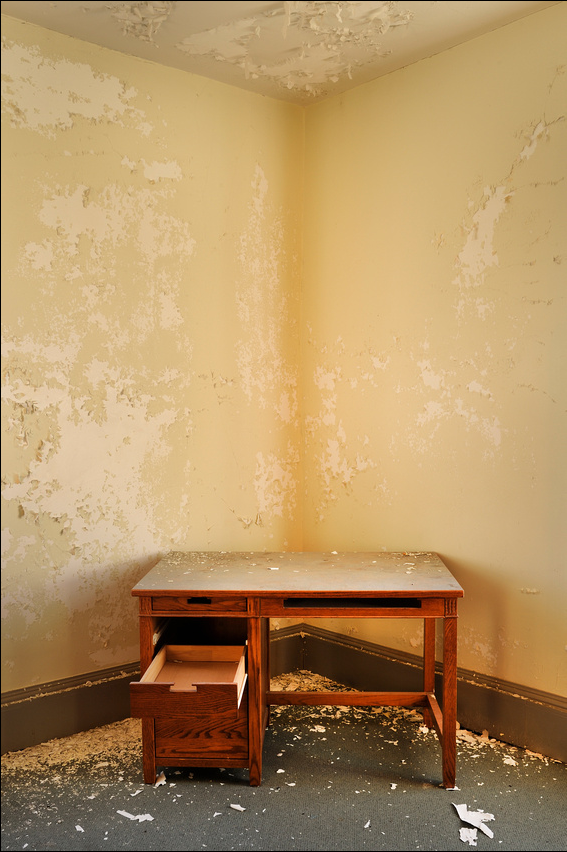

But Morris Brown largely closed its doors after losing accreditation in 2002. Thirteen years later, Stanley Pritchett, Morris Brown’s current president, is still fighting for the college’s life, selling assets and paying debts while the buildings sit largely deserted and slowly eroding. Those are the circumstances photographer Andrew Feiler captures in a new book of 60 pictures taken of the Morris Brown campus over a year. Without Regard to Sex, Race, or Color (University of Georgia Press) takes its title from an inscription on a clock tower bell (pictured below) that reads, in part, "Dedicated to the Education of Youth, Without Regard to Sex, Race or Color."

Feiler answered questions about his new book via email.

Q: In an introductory passage, you describe some of the overarching questions that drew you to this story ("How do we create opportunity for all in America? How do we create on-ramps to the middle class?"), but how did you come to Morris Brown and this project in particular? Did you have any connection or familiarity to HBCUs going in?

A: Almost everything in the South has to be viewed through the prism of race. As a fifth-generation Georgian, and having grown up Jewish in the South, I have been shaped by the complexities of the South and of being a minority in the South. History, culture, race, injustice, progress … these are all parts of that complexity. When I read of Morris Brown’s bankruptcy filing, it felt like an important story along multiple dimensions: race, social justice, economic opportunity, religion, history. I didn’t have any direct connect with HBCUs and wasn’t sure where this story would lead, but it was a story I wanted to explore.

Q: You spent a year shooting these photos. Can you describe that process?

A: The school experience is one that’s very familiar to almost all Americans. The collegiate experience is one that's familiar to many Americans. In the year that I spent shooting this work, I went looking for stories in these stilled classrooms and hallways, and I went looking for visual moments that illuminated stories. Chalkboards, desk chairs, locker rooms, band instruments … these are a visual language that connect each of us to the Morris Brown story and make it an American story.

The book opens with 10 historical images of the Morris Brown campus. The images date from as late as 1947 and as recent as 1986. They show people enlivening these spaces. There are no people specifically in any of my contemporary images, and yet by tapping into the iconic elements of the American educational experience, one feels the human presence in the stories. The feel of that human presence is one of the dimensions of this work that is resonating.

Q: What would you say these photographs tell us about the role of black colleges in America?

A: As part of this project I did a lot of research on HBCUs, and one statistic is striking: the roughly 100 HBCUs that remain are a mere 3 percent of colleges in America, but [their students] represent more than 10 percent of African-Americans who go to college and more than 25 percent who graduate with degrees. To me the key is choice. Faced with a choice, some folks choose HBCUs. It is choice that makes these schools an essential element in building a healthy American middle class.

Q: What have you taken away from this project? Those questions drew you in, but did you find answers?

A: There is a Morris Brown narrative in these photographs; there is an HBCU narrative. But when you consider the iconography of empty classrooms, hallways and locker rooms, the core narrative I found was about the American Dream. Education has been the foundational force in creating the very idea of the American Dream. Some of our most prestigious colleges predate the American Revolution. Free public education and land-grant colleges are mainstays of the American middle class. Historically black colleges, founded mostly in the decades after the Civil War, have been essential in creating opportunity for generations of African-Americans. The educational provisions of the GI Bill transformed America from relatively poor to relatively prosperous. Brown v. Board of Education was one of the high-water marks of the civil rights movement.

Gaines Hall was built in the 19th century and is one of the oldest and most historic buildings on the Morris Brown College campus. Tragically it was consumed by fire in September and may not survive. There are five images in book from Gaines including the cover photograph. Sara Allen Quadrangle was damaged by fire several years ago and has already had to be demolished. The horror of these events speaks to the fragility of all of our historical resources.

Photographs appear courtesy of Andrew Feiler.