You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Though far from ideal, student debt levels and tuition pricing continue to level out since the recession.

During the recession, college prices increased steeply while borrowing rose rapidly. Loan defaults increased, too. Now borrowing has declined slightly for the fourth straight year, defaults have steadied and tuition increases at public universities over the past three years have been at their lowest levels since the 1970s, according to the College Board’s 2015 “Trends in Higher Education” reports.

“There was a lot of very active concern about whether the trends that emerged during the worst of the recession would continue,” said Sandy Baum, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and a professor of higher education at George Washington University. “If you just read about student debt in the newspaper, you would think that suddenly it just exploded. But actually things are slowing down a little bit.”

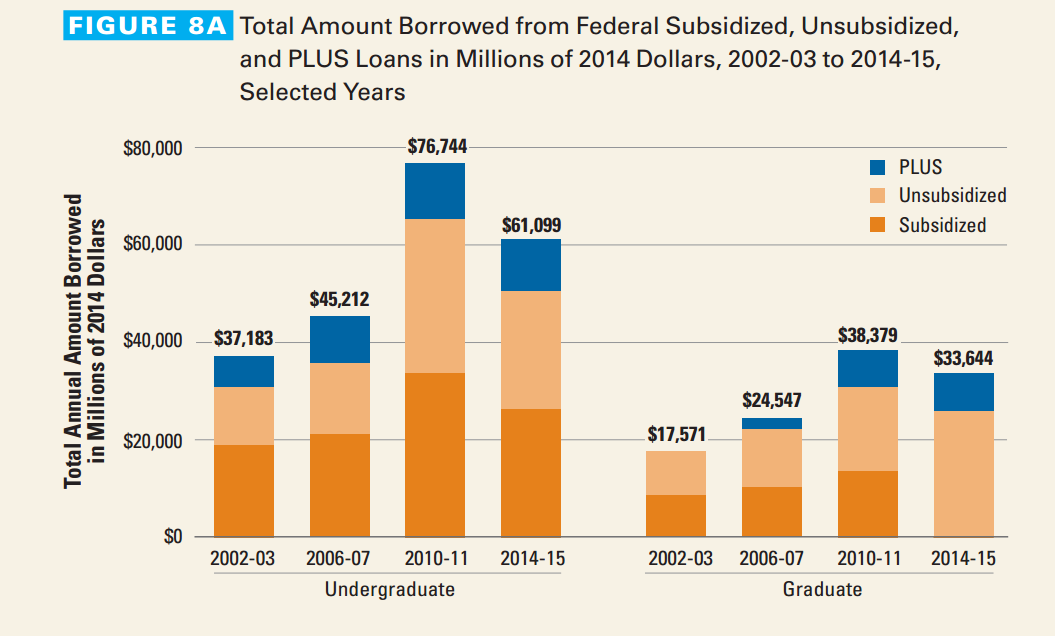

Baum helped author this year’s “Trends in College Prices” and “Trends in Student Aid” reports, released today. Starting in 2010, Baum said, worrying trends such as high borrowing started to turn around. For example, undergraduate borrowing of federal loans increased by 60 percent in the years surrounding the recession, from the 2006 academic year to the 2010 academic year. But federal borrowing declined 20 percent between 2010 and 2014.

Undergraduates in the last academic year averaged $14,210 in federal aid, including $8,170 in grants, $4,800 in federal loans, $1,170 in education tax credits and deductions, and $70 in work-study funds, according to the reports. These numbers represent a decline from recession-era federal borrowing.

In the 2014 academic year, the average undergraduate who borrowed from the Stafford Subsidized Loan Program borrowed $3,750, or 9 percent less than in 2010; the average undergraduate who borrowed from the unsubsidized version borrowed $4,125, or 11 percent less than four years earlier. PLUS loan borrowing also declined 9 percent during this time.

However, a report released by the Institute for College Access and Success last month found overall debt -- from both federal and private lenders -- for students who took out student loans and graduated with a bachelor's degree in 2014 was $28,950, up 2 percent from the year before and 56 percent more than their peers from 10 years earlier.

Meanwhile, according to the College Board reports, the number of students taking on debt is growing. Fully 64 percent of undergraduates did not take out federal subsidized or unsubsidized student loans in 2014, down from 72 percent who didn’t borrow a decade earlier.

Completion a Key Factor

A large reason for the decline in debt and defaults is because a specific type of student that was abundant during the recession -- students who went to college because they couldn’t find a job or didn’t know what else to do in a bad economy -- is much less prevalent nowadays. Such students attended for-profit colleges in droves, racking up a lot of debt in the process and not always completing their degrees.

And while enrollments are down overall in higher education, most for-profits have seen big declines. The community college sector also has seen an enrollment dip, but to a lesser degree. Total postsecondary enrollment, which increased by 20 percent between 2005 and 2010, declined by 3 percent between 2010 and 2013. In the for-profit sector, enrollment declines were much steeper at 17 percent.

“Those students who had gone back to college because they couldn’t find good jobs were students who tended to borrow a lot, who depended a lot on Pell Grants and who tended to default on student loans,” Baum said.

“All of these things are much more moderated” now, she said. But Baum added a note of caution: “It doesn't mean that any of the issues have disappeared. We should be concerned about college affordability, student debt, the effectiveness of grant aid, but we should be able to see them as long-term questions that we need to find the answers to.”

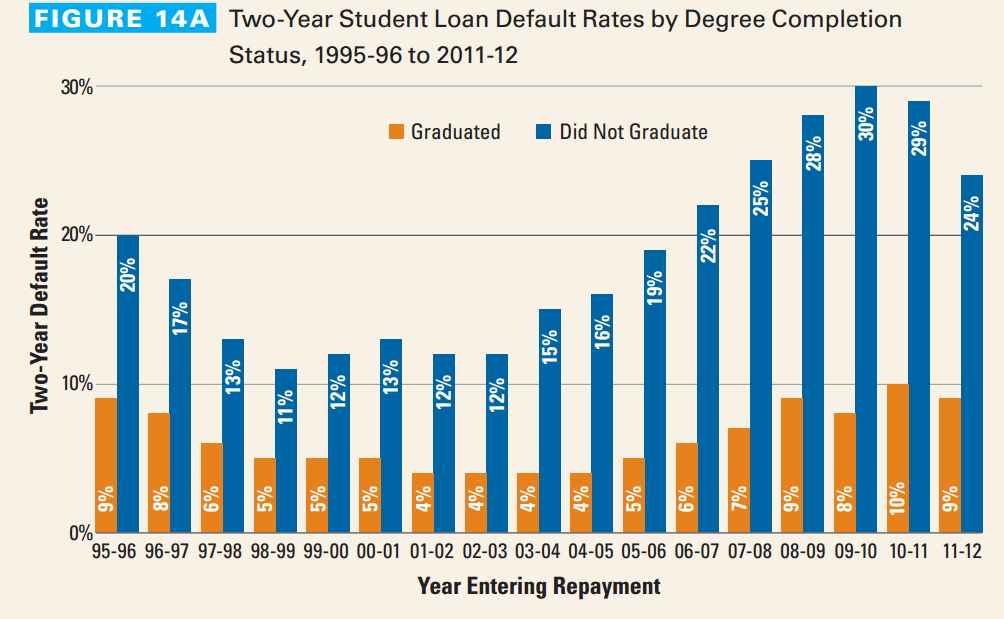

Baum emphasized that certain borrowers are more at risk than others. Completion is a key risk factor, she said.

For example, a borrower who completed his or her degree and entered repayment in 2011 had a 9 percent chance of defaulting on the loans within two years of entering repayment. That likelihood nearly tripled to 24 percent for borrowers who didn't complete their degrees, according to the reports. Meanwhile factors like race and age also appear to play a role in repayment -- black borrowers have higher default rates and borrow more than their white or Hispanic counterparts. And older borrowers are more likely to default than younger borrowers.

Though the difference in default rates between borrowers who complete their degree and who don’t has existed for decades, it has grown in recent years. Baum called the difference “startling.”

Knowing who defaults is “really different than saying that everybody who goes to college is at risk,” and is a good data point for policy analysts to keep in mind as they look for ways to minimize default rates, Baum said.

“To have all these people go to college, not graduate and then default on their student loans -- this is a real problem,” she said, “and it’s a very different problem from saying, ‘Oh my gosh, in general students are borrowing too much.’”

Default rates have lowered or remained relatively steady in recent years, following years of growth leading up to, and during, the recession. For example, the most recent cohort studied by the College Board -- students who began repayment in 2011 -- had two-year default rates of 24 percent for those who didn’t complete their degree and 9 percent for those who did complete their degree. Two years earlier, 30 percent of students who didn’t complete their degree and 8 percent of students who did were in default two years into repayment.

Meanwhile, just a small minority of borrowers owe six figures or more. In 2014, 4 percent of graduate and undergraduate borrowers with outstanding education debt owed $100,000 or more. Fully 39 percent owed less than $10,000, and another 28 percent owed between $10,000 and $25,000, according to the reports.

And the majority of debt is held by borrowers who are wealthy or middle income. Nearly half of debt (47 percent) is held by borrowers who are in the upper income quartile, meaning they earn more than $90,000 a year. Another 25 percent of debt is held by people who earn between $48,000 and $90,000 a year.

Tuition Rising Slowly

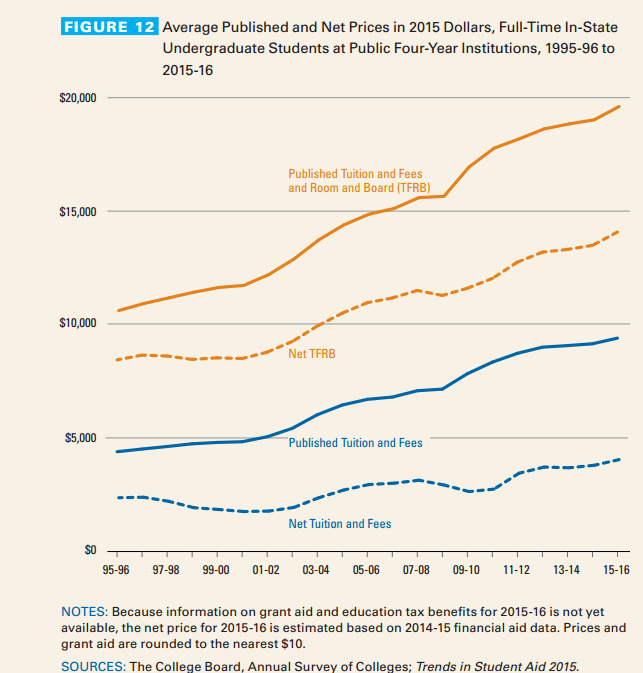

While tuition is rising continuously each year, the College Board found that the increases of the past decade are actually less steep than in previous decades.

During the last decade, four-year public colleges and universities increased their tuition at an average annual rate of 3.4 percent per year beyond inflation, compared to average annual increases of 4.3 percent in the previous decade and 4.2 percent the decade before that. Private, nonprofit colleges increased tuition an average of 2.4 percent per year during the past decade, less than the 3 percent average the previous decade and the 3.4 percent average the decade before that, according to the reports.

Yet while annual increases have been more moderate in the past decade, the average inflation-adjusted net price -- the actual amount a student pays after factoring in grant aid and, in the College Board’s calculations, tax benefits -- has increased for four-year public and private universities (but decreased for two-year colleges). Some have criticized the College Board's reports in years past for using tax credits to determine net price, arguing that families do not receive them when the tuition bill is due and the funds are necessary.

At public four-year colleges, net tuition and fees averaged $3,980 in 2015-16 -- $1,100 higher than a decade earlier, when adjusted for inflation. The average net tuition and fees for private nonprofit four-year colleges was $14,890 in 2015-16, or $190 higher than a decade ago, according to the reports.

In the last decade, net price has been affected by fluctuations in federal funding. There was a steep increase in federal aid surrounding the recession -- some of which is due to funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 -- and a subsequent decline of federal aid in years afterward. For example, in 2007 undergraduate net tuition at a public, four-year institution was $3,070, but lowered to $2,570 in 2009, during the recession, and then rose to $3,980 this year.

Inflation-adjusted grant aid per undergraduate student increased by 56 percent between 2004 and 2014, with only 7 percent of that increase between 2010 and 2014.

Take Pell Grants as an example. When adjusted for inflation, total Pell Grant expenditures increased from $16.5 billion in 2004 to $39 billion in 2010-11, but declined to $30.3 billion by 2014. Pell Grants were about a quarter of all federal aid funding in 2004. They grew to a third of all federal aid funding by 2010 and went back down to a quarter in 2014, according to the reports.

The result is that students overall are paying more for tuition now than they did in the years surrounding the recession. And lower aid levels and continuous tuition increases can be a troubling trend, even if the increases remain moderate, compared to previous decades.

“Those programs are in place but not continuing to grow very rapidly,” Baum said. “A note of caution that even small increases in tuition can be pretty significant in term of how students can pay for college.”

She continued: “That can clearly add up to a real problem.”