You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

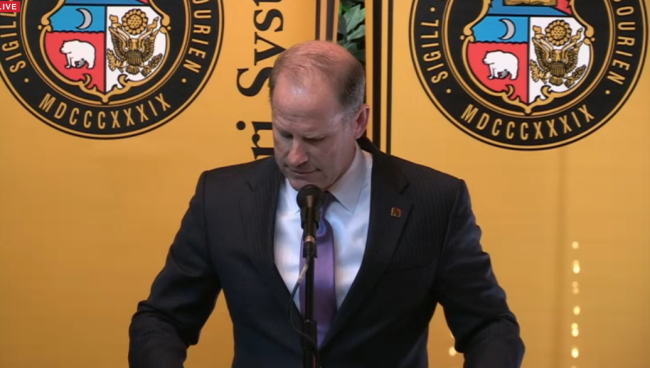

Tim Wolfe chokes up as he reads a Bible verse upon announcing his resignation.

U of Missouri

Tim Wolfe’s undoing may have been the moment he refused to step out of his car during the University of Missouri homecoming parade last month.

Wolfe resigned Monday, after student and faculty activists had been asking his administration for weeks to combat racism on the flagship Columbia campus. Protesters say they were ignored and that, when they finally did meet with the system leader, he minimized their concerns.

The system's governing board on Monday also announced that R. Bowen Loftin, chancellor of the Columbia flagship campus, would step down in January. In addition, the board promised a number of initiatives aimed at promoting diversity and inclusion.

Perhaps the most visible moment of disconnect between the students and their leaders came at the Oct. 10 homecoming parade, when a group of black students, members of the organization Concerned Student 1950, confronted Wolfe while the president sat in the backseat of a convertible during the procession. Wolfe refused to get out of the car and engage students, and some students claim the car struck them, although the university disputes those claims.

Unrest has continued to snowball since the incident, and critics say his response was too delayed. Wolfe met with student activists two weeks later, but the two sides apparently did not find much common ground. And when he did apologize, it was nearly a month after the parade.

Meanwhile, after the parade and other allegations of racist incidents at the flagship campus in Columbia, a graduate student went on a hunger strike and a group of black players on the football team -- with their coach expressing support on Twitter -- vowed to boycott games until the president resigned.

Over the weekend students camped out on campus and said they would remain there until Wolfe resigned. Several others, from two Republican lawmakers to the state's governor to graduate student groups, also called for Wolfe’s resignation. On Monday, the university's student government formally called for Wolfe’s resignation, and faculty members encouraged students to walk out of classes in protest of Wolfe’s leadership.

So on Monday morning, at the start of a last-minute governing board meeting, Wolfe acquiesced to the calls to resign.

“The frustration and anger that I see is clear, real, and I don't doubt it for a second,” Wolfe said Monday in an at times emotional address to the university. “We stopped listening to each other, we didn't respond and react, we got frustrated with each other.”

'Language Matters'

Calls for dismissal are not isolated to just Wolfe. On Monday, in a letter sent to the UM Board of Curators, nine Missouri deans said they wanted to express "our deep concern about the multitude of crises on our flagship campus." They called for Loftin's dismissal.

“This thing just exploded,” said E. Gordon Gee, president of West Virginia University and former president of Ohio State University. Gee and several leaders in higher education interviewed for this article said it is extremely rare for a president of a large university system to be forced to resign amid a fervor of student activism.

“The university leadership didn’t respond quickly and forcefully to the issues … they tended to be perhaps too passive,” Gee continued. “Any of these kinds of issues, people look to the leadership of the university to address them.”

Indeed, Wolfe and system administrators have been faulted with failing to react in a timely manner to student concerns.

“He has not only enabled a culture of racism since the start of his tenure in 2012, but blatantly ignored and disrespected the concerns of students. The University of Missouri System has heard student pleas behind closed doors with no effective response,” the student government wrote in a letter to Missouri’s governing board. “While we recognize the burden of systematic oppression does not fall entirely on his shoulders, as the leader of this system it his sole prerogative to listen and respond to students. He has failed in this completely.”

When the student government president, who is black, tweeted about how someone called him a racial slur while walking on campus, there was an outpouring of support on Twitter. Yet there was also an outpouring of frustration with the Missouri administration for not responding or reacting to the student’s experience.

Then a student group, the Legion of Black Collegians, posted about how some of its members were also called racial slurs while rehearsing for a campus event. Loftin posted a video acknowledging and condemning racism on campus, but Wolfe and fellow system administrators remained silent.

For many frustrated students, the silence was reminiscent of a lack of timely and clear responses to student demands for more minority enrollment, and of the perceived silence following student frustrations after the shooting of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., made headlines and placed Missouri at the center of a national conversation about race.

“If you’re in a leadership position, a presidential position, language matters. How you respond matters. The message you send matters. Students in this community wanted to feel that they were heard and the concerns they had were legitimate, and unfortunately they didn’t get that,” said Kevin Kruger, president of NASPA: Student Affairs Professionals in Higher Education.

“Campuses have to respond proactively to incidents related to racial intolerance,” he said. “In today's world you can't assume that small acts of protests are isolated.”

On Monday, the system governing board's chairman, Donald Cupps, issued a forthright apology for the university's perceived inattention to the concerns expressed by students and others about the racism they perceive at the institution. “Significant changes are required to move us forward. The board is committed to making those changes,” he said.

The board promised to appoint a diversity officer for the system and review student and staff conduct policies, as well as provide additional support for hiring and retaining minorities and assisting students who have experienced discrimination. The board did not make any promises to increase the number of black students enrolled in the system, as has been requested by some protesters.

In many ways, the events at Missouri show how social media has changed the nature of student activism. Graduate student Jonathan Butler's hunger strike had a larger impact than it would have several years earlier, because Butler had a platform like Twitter to share his protest with thousands of supporters. Social media has also shortened the time span in which a university is expected to respond, Kruger said.

And the fact that much of the football team joined the protests, boycotting practices and games until Wolfe resigned, further escalated activism on campus and in part precipitated Wolfe’s resignation.

Minority students have been rallying at campuses around the country in recent years, often seeking to increase minority enrollment and to combat racism. Black student organizations at the University of Michigan and Harvard University, for example, launched yearslong social media campaigns, on-campus rallies and sit-ins in an effort to encourage more progressive enrollment policies. Yet in those cases, administrators and students eventually worked together and found common ground.

Until this week at Missouri, no campus had seen unrest intensify to the point where the university’s major athletic team joined the protests. In Missouri constituencies that are often disconnected -- everyone from faculty to graduate groups to lawmakers to student athletes -- have been united in seeking what they say is a better response to racism on campus. John Lombardi, former president of the Louisiana State University system and the University of Florida, said the football team’s participation in the protests elevated the visibility of tensions at Missouri.

“The unique feature of this particular case is the mobilization of students who command a high-visibility platform within and without the university,” he wrote in an email. “These are not the only students mobilized in this case, but they provided a visibility that greatly enhanced the issues raised by other student constituencies, and so this protest gained momentum and political power.”

Benjamin D. Reese Jr., president of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education, said tensions had escalated to such a crescendo at Missouri it was untenable for Wolfe to remain the system’s leader.

“What might that imply about the very culture of a university?” he asked. “We don’t have two or three students in protest. We have a wide cross section of students. We have faculty.”

Added Kruger: “It’s probably the best thing for the institution moving forward to have a fresh approach with students on the campus. To try to recalibrate their approach.”