You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The term "first generation" tends to be thrown around a lot by educators and policy makers. But what does the term mean?

Does a first-generation college student come from a home where neither parent earned a college degree? What if at least one parent graduated college? What if their parents attended college but didn't graduate? Does it matter if it's a biological parent that attended college or some other adult residing in their home?

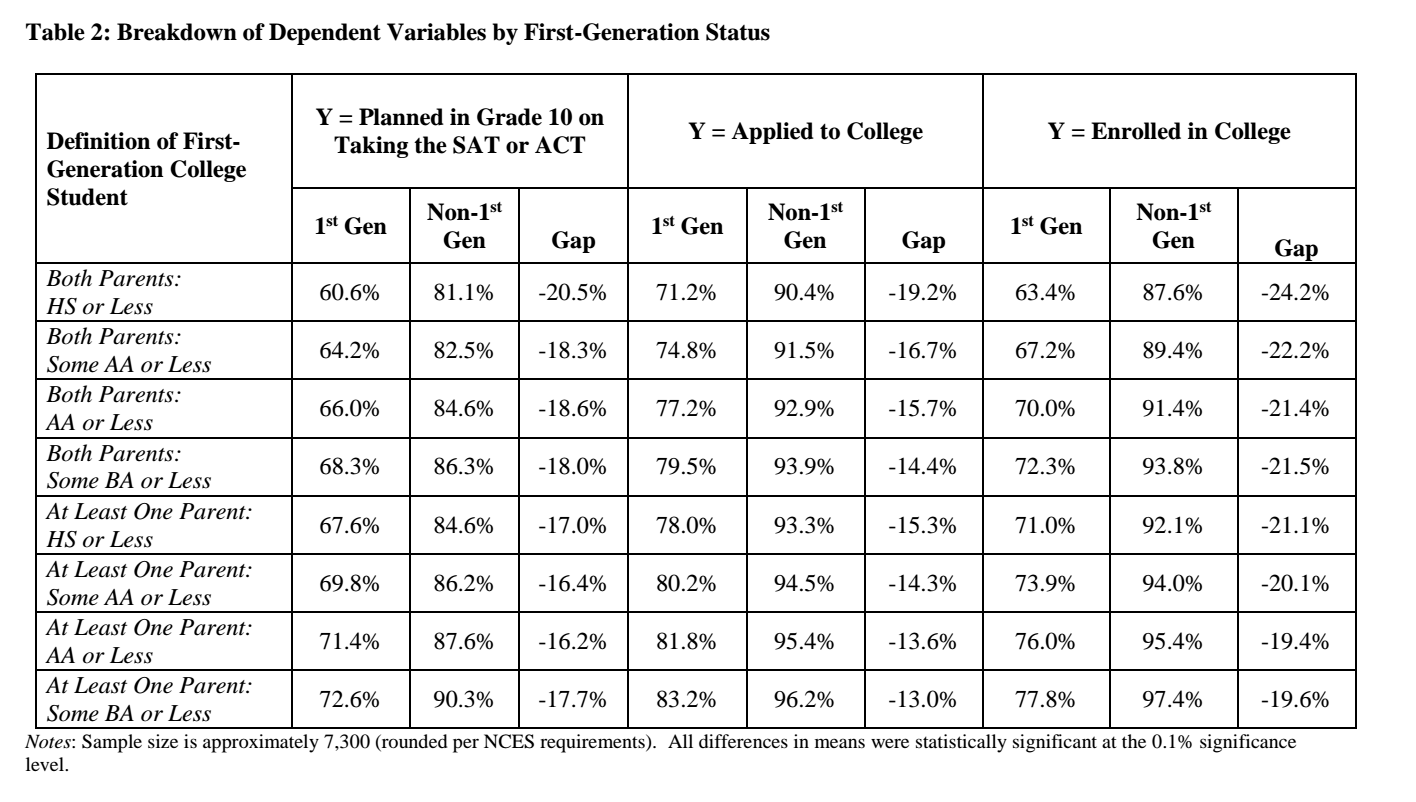

New research from the University of Georgia's Institute of Higher Education, presented last week at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, explores whether different definitions of "first generation" change (a) how many such students there are and (b) our understanding of how they fare in higher education.

The answer to the latter question: not really. Regardless of how they're defined, first-generation students enroll and graduate at lower rates than do other students. But the definition has an enormous impact on the size of the population of students, the researchers found.

"No one has defined what they mean by 'first generation,'" said Robert Toutkoushian, a professor at Georgia and the lead researcher of the paper "Talking 'Bout My Generation: Defining First-Generation Students in Higher Education Research."

The researchers found that of the 7,300 students they studied from a 2002 longitudinal study, the number of students defined as "first generation" could vary from as small as 22 percent to as large as 77 percent, he said. So the broader the definition of "first generation," such as including students with one parent who has collegiate experience, the larger the population.

The definitional question matters because the mounting pressure to increase the rate of college attainment among U.S. adults is complicated by the fact that first-generation students -- who make up growing numbers of the target population -- are less likely to pursue bachelor's degrees.

According to the Center for Community College Student Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin, 47.2 percent of what it defines as first-generation students made transferring to a four-year college or university their primary goal compared to 56.1 percent of non-first-generation students. About 67 percent of first-generation students said their primary goal was to obtain an associate degree, compared to 60.3 percent of non-first-generation students. First-generation students also showed more interest in completing a certificate program compared to non-first-generation students, 33.6 percent to 27.7 percent. The center defines students with at least one parent who has attended college as non-first-generation.

But Evelyn Waiwaiole, director of CCCSE, said it's difficult to unpack those statistics because we don't have a better understanding of who first-generation students are.

"If we want more first-generation students to have the goal of transferring to a four-year, we have to understand the dynamics behind being first generation," she said. "It's not just because you're probably first generation -- it's probably other variables involved, and if we're going to put other policies and practices in place, we need to have a richer understanding."

For example, these first-generation students may want to stay closer to home and may not live near a four-year college, which might play a role in the type of higher education they pursue, she said.

And the idea of a first-generation student today is different from what it was 50 years ago, Waiwaiole said -- "What if your brother or sister went to college?"

The Georgia researchers used longitudinal data from 2002 to better define the first-generation student. They examined the various education levels of one or both parents and how it affected whether a student planned to take the SAT or ACT in 10th grade, applied to college or enrolled in college.

They found, for instance, a student's initial interest in attending college varied greatly depending on whether neither parent attended college versus everyone else who had at least one parent attending some level of college. Students with at least one parent attending college had a very similar level of interest as those with both parents having college experience, Toutkoushian said.

But when it came to enrolling in college, students with only one parent in college were at a disadvantage relative to those with two parents who had some college background, he said.

"Regardless of how we define it, first-generation students are at a disadvantage when compared to non-first-generation students," Toutkoushian said.

Toutkoushian admits that defining first-generation students doesn't answer many of the questions he has posed, such as the effect of a sibling or relative attending college on a first-generation student, or if at least one parent has a graduate-level education.

"Probably the biggest thing we can do is work within schools to provide kids with information about college options early," Toutkoushian said, adding that there has been research that has shown about half of students decide they plan to attend college before the sixth grade. "And interventions should happen early, so we're not waiting until high school and we're getting them in middle school."

And although education levels are rising, Toutkoushian said policy makers shouldn't expect to have fewer first-generation students.

"The fastest growing demographic is Hispanics and Latinos and they tend to have lower educational levels than non-Hispanics and non-Latinos," he said. "So we might have more first-generation students moving forward."