You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

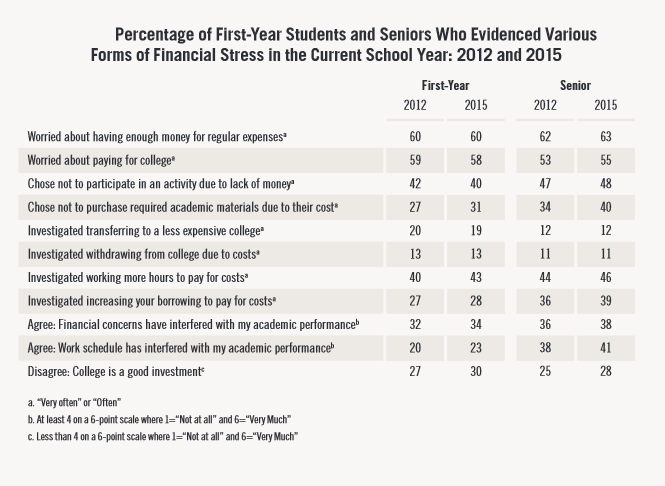

In 2012, the annual National Survey of Student Engagement found that -- in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and recession -- financial stress was a particular concern for students and they felt the stress undermined their undergraduate experience. About 60 percent of students said they frequently worried about having enough money for regular expenses, and slightly less than one-third said they did not purchase required academic materials because of the cost.

Three years, later, although the economy has improved somewhat, little has changed. A report detailing the results of this year’s engagement survey asserts that financial stress for students has not abated. And in some cases, it has actually gotten worse.

In 2012, 27 percent of first-year students said they had eschewed buying required materials due to their cost. In 2015, 31 percent said they did not buy some materials. Among seniors, those who did not purchase required materials accounted for 40 percent of students.

More than half of students -- freshman and seniors alike -- said they were worried about paying for college. About 40 percent of seniors and 23 percent of first-year students said their work schedule interfered with their academic performance. Sixty percent of students said they were worried about having enough money for regular expenses.

For black and Hispanic students and those from other underserved groups -- such as first-generation students -- the level of financial stress and its effects were even higher.

“The economy has improved, but we’re not seeing much of a change in perceptions of financial stress, and in some cases we’re seeing an uptick,” Alex McCormick, director of the National Survey of Student Engagement, said. “Financial stress appears to be very real.”

The good news, McCormick said, is that financial stress seems to have had little effect on how much time students devote to academic work. First-year students with higher levels of financial stress spent only one hour less per week preparing for class than did students who reported lower levels of stress.

At the same time, students reporting high levels of financial stress spent “substantially more time working, commuting and caring for dependents than their low-stress peers,” the report stated. Also concerning, the researchers said, was how the students rated the campus environment. Students experiencing high levels of financial stress -- which is calculated using a 60-point scale -- rated their interactions with other students less favorably and “perceived a less supportive environment.”

“Their lower ratings of interactions with others and environmental support are cause for concern,” the researchers wrote. “Given their time commitments and the amount of debt most students incur to attend college, financially stressed students have limited availability to work more or to take on additional debt.”

Black and Hispanic students -- whom the researchers found to be especially at risk for financial stress -- also reported having lower-quality interactions on campus than white students did, especially with faculty members. About 52 percent of first-year white students rated their interactions with faculty highly, compared to 43 percent of first-year black students and 46 percent of Hispanic.

Also concerning for underserved students, McCormick said, is a finding from the NSSE's companion survey, the Beginning College Survey of Student Engagement. The survey found that there is "considerable consistency" in study time between high school and the first year of college.

More than two-thirds of students who reported studying more than 15 hours a week in high school said they studied at least that much as freshmen. For students who studied five or fewer hours a week in high school, only a quarter reported studying 15 hours per week in college. This can mean first-generation students who have yet to pick up effective study habits may find themselves floundering once they reach college, McCormick said.

"Improvements can happen," he said. "But it's well-known that the best predictor of behavior is prior behavior. K-12 education and higher education need to more explicitly equip students with tools to be successful academically, and not just assume that students are going to pick those up on the way or from their parents and siblings. That reinforces social class advantages."

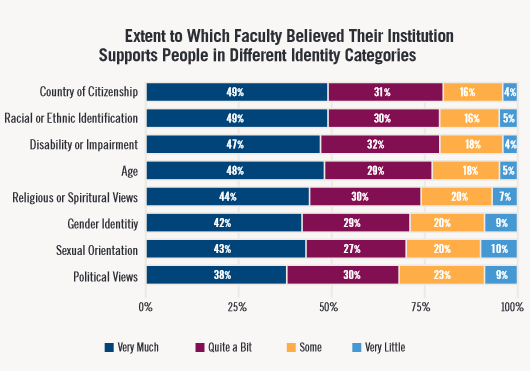

The majority of faculty members, however, said they believe their institution is already supportive of students of color and other underserved groups.

The report included some data from the related Faculty Survey of Student Engagement. That survey found that 80 percent of faculty members at 16 four-year institutions that answered this particular question said they “very much” or “quite a bit” believe that their institution supports racial and ethnic minority students.

Relationship Between Engagement and Challenging Courses

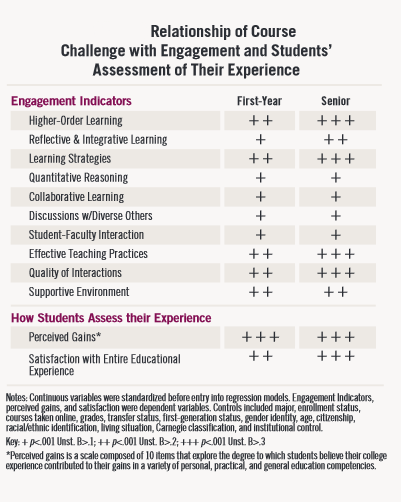

This year’s student engagement survey -- which collected responses from 315,000 first-year and senior students at 585 four-year institutions -- also examined the links between student engagement in a course and how challenging the student found that course.

The survey asked students the following question: “During the current school year, to what extent have your courses challenged you to do your best work?” Students responded by using a seven-point scale, with one meaning “not at all” and seven meaning “very much.”

First-year and senior students who indicated that they were highly challenged by their courses were more likely to engage in what the researchers consider to be effective or “high-impact” education practices, including high-order learning and integrative learning. In turn, senior students who reported engaging in those practices said they felt more prepared for their postgraduation plans.

Only 54 percent of first-year students and 61 percent of students said they felt highly challenged, however.

“We see barely half of first-year students saying they're highly challenged,” McCormick said. “I think we can do better. The root of academic success is a combination of challenge and support. You set high expectations and then try to stretch students to perform beyond what they think they’re capable of doing. But you do that in an environment where you provide support for them to be successful.”

How challenging a course was perceived to be varied greatly among differing majors. More than 71 percent of those working toward a degree in a health profession said they were challenged, while just over half of students majoring in communications, media and public relations reported feeling challenged.

Nontraditional-aged students were more likely to feel challenged by a course than were traditional-aged students. For nontraditional-aged students, taking courses online seemed to play a role in how challenged they felt. Three-quarters of students taking all of their courses online reported feeling highly challenged, compared to two-thirds of students taking some or no online courses.

The selectivity of an institution had little effect on how challenging students felt the courses were, continuing a trend from last year’s survey that found selective institutions are not more likely to produce higher levels of student engagement or quality of interaction.

Highly selective colleges and universities -- as defined by the selective index used in Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges -- made up 9 percent of all institutions in this year's survey. When the researchers identified the top 50 institutions where students said they felt challenged, highly selective institutions accounted for 14 percent for first-year students. No highly selective institutions made the top 50 for seniors.

“Are more selective institutions more successful at eliciting the best work out of their students? The answer seems to be no,” McCormick said. “The idea that selectivity guarantees you a better experience is, in fact, not a guarantee.”