You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

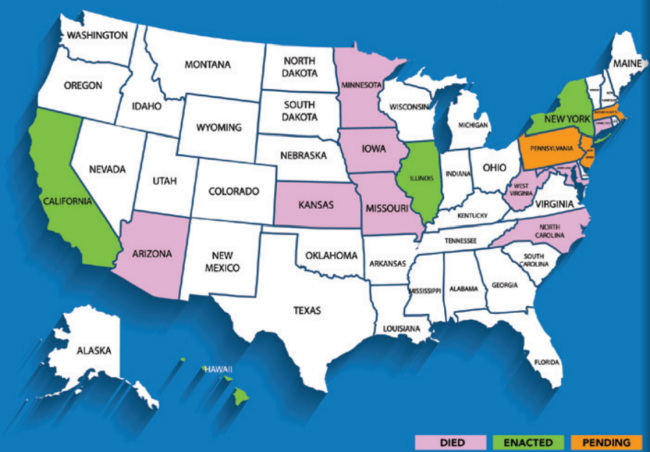

Status of laws defining affirmative consent

NASPA/ECS

Impatient with attempts by both colleges and Congress to address the issues surrounding campus sexual assault, legislators in at least 28 states this year introduced bills on the topic, according to a report released today by the Education Commission of the States and NASPA: Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education.

The report categorizes the bills into four primary -- and often controversial -- policy themes: affirmative consent, the role of local law enforcement, transcript notation and the role of legal counsel.

“We’re seeing a recent uptick in the number and variety of legislative proposals across states that would bring change to how college administrators prevent and address sexual violence on campus,” Andrew Morse, director of policy research and advocacy with NASPA, said. “We were interested in finding out what some of the themes and nuances were across the states and what the proposals would mean in cases where they supersede federal law and guidance from the Department of Education.”

Earlier this year, NASPA led more than a dozen student affairs associations and campus safety groups in penning an open letter to legislators in all 50 states, urging them to reconsider pending bills that would give accused students judicial rights, such as allowing a lawyer to fully participate in campus hearings, or would require college officials to refer all reports of sexual violence to law enforcement. Such mandatory-referring bills could force colleges and universities to be out of compliance with federal law, the groups worried.

A provision in the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 amendments to the Clery Act, the law that mandates that colleges track and publicly report instances of certain crimes each year, states that institutions that receive federal funds must inform victims of sexual assault that they can decline to notify law enforcement about being assaulted. Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972 also allows certain employees, such as counselors and advocates, to not report incidents of sexual assault.

In January, the Virginia Senate considered a bill that would have required public colleges to report an alleged campus sexual assault to police within 24 hours. College employees who failed to report an assault to police would have been charged with a misdemeanor. After hearing from survivors and victims' advocates, state legislators retooled the plan to promote what one senator called “enhanced encouragement” instead.

The version of the bill that finally passed -- and that is detailed in the new NASPA and ECS report -- requires employees of public and private institutions who learn of a sexual assault to report the information to the campus Title IX coordinator, who must meet with a review committee within 72 hours to discuss the case. If the committee determines that the misconduct poses further risk to the health and safety of the victim or others on campus, then the institution is required to report the crime to local law enforcement.

California adopted similar legislation, which requires public and private institutions to report any violent crimes that occur on campus to local law enforcement. According to the report, comparable bills were introduced but defeated in Maryland, Missouri, New Jersey, Oklahoma and Rhode Island, and are pending in Massachusetts and Delaware.

“Policy actions and campus support systems must prioritize the rights and choices of survivors,” the report stated, urging states to steer clear of such legislation. “To this end, state and campus policies should enable the survivor to choose her or his path for resolution or support, whether through the campus or the criminal courts (or both).”

NASPA, along with 200 other groups, also condemned a bill introduced in Congress in July that would bar colleges from investigating incidents of sexual assault unless the alleged victim reported the crime to law enforcement. Called the Safe Campus Act, the proposed legislation was supported by the North-American Interfraternity Conference, the National Panhellenic Conference and the Fraternity and Sorority Political Action Committee, which spent more than $200,000 on lobbying for many of the provisions in the bill. Many critics were outraged by the legislation, which they said was designed to put pressure on victims of sexual assaults and make it more difficult for them to seek punishments of their attackers through campus judicial systems.

Due process advocates and fraternity and sorority groups at the time applauded the Safe Campus Act as providing an avenue for “much-needed reforms” to the rights of accused students, but the NIC and the NPC pulled their support of the bill in November amid backlash from their member chapters. Morse, of NASPA, said he remains worried about similar provisions being introduced in state legislation.

State lawmakers have introduced a number of bills that, like the Safe Campus Act, would expand the role of legal counsel in campus conduct proceedings. So far, North Carolina and North Dakota have passed such legislation, and Massachusetts and South Carolina have also tried to do so. In North Carolina, a student who is accused of violating a public institution's rules, including those about sexual misconduct, has the right to be represented by licensed attorney. Unlike the system in place at most colleges and universities, the lawyer is permitted to fully participate in the disciplinary process, rather than simply consult with the student as an adviser.

“We have to remind ourselves that campus conduct hearings are not courts of law, and we want to caution bringing the criminal justice system onto campus,” Morse said. “We are seeing a continuation of conflating conduct processes with courts. Our responsibly is to be educational in nature and ensure access for all students to an education that’s safe, as well as of high quality.”

Other bills introduced recently would require colleges to note on transcripts whether a student was suspended or expelled over sexual assault allegations. Two states -- New York and Virginia -- have adopted the legislation, and it remains under consideration in Pennsylvania. Bills in California and Maryland were not adopted.

Of the four policy areas discussed in the NASPA and ECS analysis, legislation addressing affirmative consent polices has been considered in the highest number of states. Since 2013, bills defining affirmative consent have been introduced in at least 16 states. California, Illinois and New York now require colleges to define consent as being voluntarily or freely given, and to clarify that a lack of protest or resistance does not constitute consent. If a person is incapacitated due to drugs or alcohol, is asleep, or is unconscious, consent cannot be given.

Legislation addressing affirmative consent policies has died in Arizona, Connecticut, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina and West Virginia, according to the report. Similar bills are pending in Massachusetts, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

While an increasing number of colleges are adopting affirmative definitions of consent, many state lawmakers have been hesitant to codify the definition through legislation, particularly in states where the legal definition of consent for the general population would no longer match the definition colleges would be required to use. Civil liberties organizations and legal experts -- including 28 Harvard law professors -- have also raised concerns about how changing consent policies would affect the due process rights of accused students.

“Some due process advocates have raised questions about rights for the accused, particularly since affirmative consent laws shift the burden of demonstrating the affirmation of consent from the survivor to the accused,” the report noted. “Campus officials will need to make sure the affirmative consent policies are consistently and fairly applied and that an unreasonable or uneven burden is not placed on a single party.”