You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

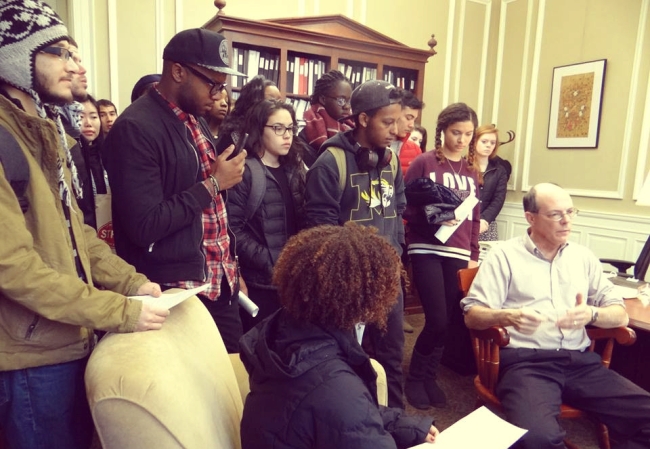

Students meet with Earlham College's president, David Dawson.

EC Students Against Racism

Earlham College regularly organizes intense meetings on campus issues, with faculty, staff and students all getting a chance to speak. That's what the Indiana college did Thursday when it canceled classes to allow hundreds of students and faculty to gather with administrators in the campus gymnasium and discuss diversity concerns raised by a group of students.

More unusual is that the concerns were presented earlier in the week as a list of demands. Protests by minority students in recent months have featured many similar lists, but the idea of students making demands is virtually unheard of at the Quaker college.

At Earlham, less than 10 percent of students are Quaker, and the small Quaker population nationally means that colleges in the faith almost by necessity welcome people of a variety of backgrounds. But one aspect of the religion that many students and alumni agree has remained a core part of the college is its commitment to Quaker-based consensus.

Deliberate and methodical, it’s a style of governance that is central to the religion and to Earlham.

“Canceling classes and having a big meeting, that’s a very Quaker thing to do,” Tom Thornburg, a former Earlham trustee who is now a senior associate dean at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said. “Consensus is generally used throughout student government and the administration, and Earlham does as good a job as any institution with involving students in administrative decisions. You bring people together in a room and you hope you make a decision by agreement. So in that environment, a list of demands is always kind of awkward.”

Consensus, he explained, is a form of governance that is based on trust and on sharing a variety of opinions. In generations past, the form of governance helped lead Quakers to be abolitionists and supporters of the civil rights movement before many others. But the discussions, Thornburg admitted, can sometimes be a “pretty slow process.”

According to a guide about the consensus process, Earlham students and faculty are expected to avoid forming any opinions before a “group dialogue on an issue” has started. “Consensus is a group deliberation process based on the assumption that all who participate in the process are eager and open to finding a basis for right action,” the guidelines state. “Group members’ devotion to group deliberation and shared insight should be greater than to their own opinions on a matter.”

However, consensus does not assume full participation of every person within a community, the guidelines warn, but instead “utilizes the delegation of responsibility to groups or individuals.” Despite the college’s attempts to include students in much of these discussions, some minority students felt their concerns were not being heard, let alone being brought up for consensus.

Last week, a group of those students, calling themselves EC Students Against Racism, marched across campus and presented a letter that included a "list of requirements concerning students of color" to the college's president, David Dawson.

The students' requirements for the college include that Earlham create a multicultural center that provides counseling and is staffed by people of color, that it more easily allow for exemptions from "expensive and mandatory housing and meal plans," and that it offer diversity training for all students, faculty and staff. Among other requirements, the students also demanded that at least 30 percent of the college's faculty, staff and administrators and 20 percent of the Board of Trustees be people of color by 2020.

About 23 percent of faculty and 8 percent of staff at Earlham are nonwhite.

"As it currently stands, this campus is unsuitable for students of color to thrive," the students wrote. "Earlham is failing to sustain the diversity that this college promises and, because of this, we cannot in good faith endorse Earlham as a place suitable for students who value diversity, fairness and equity. We consider it our duty to accurately represent our college to other students as well as the greater public. Through our combined efforts with Earlham’s administration, we hope to create a college that all students can be proud to represent as their alma mater.”

If the college were to threaten the jobs of any faculty members who supported the list, the letter warned, the college should expect “a concerted and impactful escalation.”

On Monday, Dawson, the college's president, announced that he had asked Earlham's Diversity Progress Committee, a faculty group focused on diversity efforts, to recommend that senior administrators adopt four new policies related to the list. If adopted, the new policies would include requiring diversity and inclusion training for all faculty, staff and students, establishing a "neutral personnel, place and process for complaint reporting," and creating a Student Diversity Council that would advise the faculty committee. More new policies may be adopted, the college said, after administrators and the Diversity Progress Committee determine which, if any, of the remaining student requirements are feasible.

Dawson said Earlham is a "place of a lot of meetings and gatherings responding to issues of the moment," but adding a Student Diversity Council would help students of color have a louder voice in those discussions. It's the same logic, Dawson said, that led him to cancel classes on Thursday. The last time Earlham called off classes for such a gathering was when one student was killed and two others were injured after being struck by a train near campus in 2012.

"Having special meetings is not that special for us, but canceling classes doesn't often happen," Dawson said. "When you do so, the entire community is freed up and can come together. When we do cancel class, it's often a case where there's a need to bring the community together because there is strong, emotional, personal reaction on campus. That is what occurred here."

.png)

Some students said this week that they felt Earlham's commitment to Quaker consensus was only "a marketing scheme." They called the college's response so far "necessary, but not sufficient."

"We acknowledge that true consensus is difficult among the whole student body, but we believe it is still imperative that Earlham follow out the values behind consensus, listening to all voices and understanding that all experiences are valid," EC Students Against Racism said in an email Tuesday. "Additionally, because people of color's voices are already marginalized due to structural racism and in number at Earlham, consensus here has further perpetuated this marginalization of people of color. The idea of consensus is rooted in the understanding that all voices are valuable. The actual practice of consensus at Earlham College has not been so."

Susanna Williams, a higher education consultant and a former member of the Earlham Alumni Council, said introducing a list of demands or requirements in a Quaker setting can be “awkward and problematic,” but she said she’s not surprised that minority students would choose to adopt methods similar to that of other recent campus protests, rather than stick to the more orthodox and slow-moving process of Quaker consensus.

Williams, who was born and raised Quaker and graduated from Earlham in 1997, said the college “is not a great place to be a student of color.”

While Earlham has a comparatively large minority population -- just over half of students identify as white -- many students of color are international students, not the type of domestic students who wrote the demands. Less than 13 percent of Earlham students are black, 6 percent are Hispanic or Latino, 5.6 percent are Asian, less than 1 percent are Native American, less than half of 1 percent identify as being two or more races, and 52 percent are white. About 20 percent of students are described as international students.

“Speaking to students of color this summer, they expressed feeling isolated,” Williams, who spoke to students at an event in June, said. “Students I talked to expressed feelings that they were not heard. They did not feel like they received equal treatment. There’s definitely a sense that white students have more resources and that they have a bigger platform for advocacy on campus.”

Williams and other alumni said they generally agree with many of the students’ ideas, but they aren’t sure Earlham has the resources to carry out all of the requirements. They also worry that the college's location -- in a small town in an overwhelmingly white state like Indiana -- makes Earlham an undesirable destination for many minority candidates.

“At the same time, Earlham’s commitment to social justice is very real,” Williams said. “There is commitment to making sure people are heard. I imagine people on campus were pretty hurt when this came up, but I think it will open a much-needed conversation, and no institution is better prepared than Earlham to have that conversation.”

Brian Zimmerman, the college’s director of media relations, said Thursday’s all-campus meeting lasted nearly three hours and followed three smaller group meetings. He declined to discuss what was exactly said during the all-campus assembly, but called the gathering “extremely productive and, at times, emotional.”

Zimmerman said while it is unusual for students at Earlham to present a list of demands, it is not uncommon for students to challenge the status quo on campus, and the administration does not view the list of demands as adversarial.

“As a Quaker institution, we do practice the pursuit of truth,” Zimmerman said. “We use consensus, and that can mean that not everyone is going to get their way, but it also means that everyone will listen and evaluate common concerns and themes. And then we’ll decide what is in the campus’s best interest and move on.”