You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

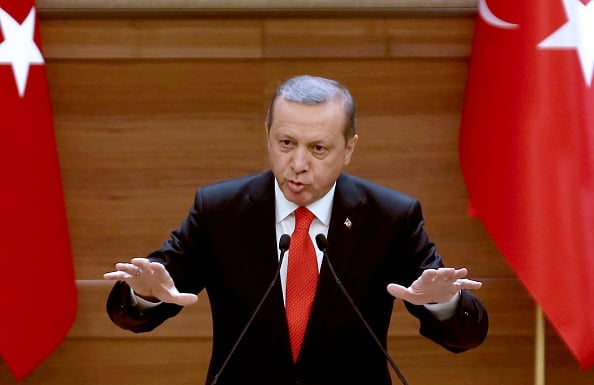

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey gives speech attacking academics.

AFP / Getty Images

In the early morning hours of Jan. 15, the antiterror police came to Yucel Demirer’s home. He was taken to police headquarters, where he shared a cell with fellow Kocaeli University professors who, like him, had signed a petition calling for an end to the military campaign against Kurdish separatists in southeastern Turkey.

Around 7 p.m., Demirer was transported to the local prosecutor’s office, where, he said, he was questioned about links to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, which Turkey, the European Union and the U.S. consider to be a terrorist organization. “They were trying to connect our petition with the PKK,” said Demirer, an associate professor of political science at Kocaeli, a public university located about 70 miles east of Istanbul. “It was stupid, but that’s what they were trying to do.”

By the end of that night, Demirer and his colleagues were back in their houses, but the saga of criminal investigations and university disciplinary proceedings lodged against signatories of the “Academicians for Peace” petition had just begun. The Dogan News Agency reported in mid-January that the chief prosecutor's office in Istanbul had opened an investigation into all 1,128 Turkish academics who initially signed the petition, which denounces what the document describes as the Turkish state’s “deliberate massacre” of Kurds in the southeastern provinces and calls for the resumption of peace negotiations.

“We haven’t slept so many nights waiting for the police to come,” said Maya Arakon, a signatory and associate professor of international relations at Suleyman Sah University, a private institution in Istanbul. “This is not what should happen to you when you only sign a petition, a peaceful petition.”

The crackdown on the professors who signed the petition -- and who, for that reason, were accused by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of “treason” -- has attracted widespread international criticism. The U.S. ambassador to Turkey, John Bass, issued a statement expressing concern about “a chilling effect on legitimate political discourse …. Expressions of concern about violence do not equal support for terrorism. Criticism of government does not equal treason.”

A spokesperson for the European Union called the actions taken against the academics “an extremely worrying development.” Myriad scholarly associations and nongovernmental organizations have written letters urging the Turkish government to respect academic freedom and freedoms of expression more generally. Thirty scholarly groups and higher education associations signed a joint letter coordinated by the Scholars at Risk network, affiliated with New York University.

“We are … dismayed to have to write now and express our grave concern about recent reports of widespread pressures on members of the Turkish higher education and research community, including investigations, arrests, interrogations, suspensions and termination of positions, in apparent violation of internationally recognized principles of academic freedom, free expression and freedom of association; principles on which quality higher education and research depend,” that joint letter states.

A separate letter from the Middle East Studies Association's Committee on Academic Freedom to Turkey's prime minister notes that this is the 20th letter the committee has written “calling upon your government to protect academic freedom in Turkey” since the general elections in 2011.

“Unfortunately, more often than not these letters have identified instances in which members of your government have used their authority to silence critics within Turkish academic circles by branding them terrorists or traitors for engaging in academic research or exercising their right to free speech to call for peaceful political change,” the letter, dated Jan. 14, states. “Equally, these cases have often arisen in the context of academics’ conducting research or publishing findings critical of your government’s policies with respect to Kurdish citizens or the Kurdish regions of the country.”

MESA’s Committee on Academic Freedom has since written three more letters of concern to Turkish government officials, bringing the count to 23. One of the new letters addresses the specific case of an assistant professor reportedly suspended by his university administration for signing the petition, while the others deal with criminal proceedings against two different Turkish academics for social media postings they’d made.

One of those two academics, Koray Caliskan, an associate professor of political science at Bogazici University, an elite public research institution in Istanbul, is under criminal investigation for Twitter posts deemed insulting to Erdogan (Caliskan maintains that the tweets constitute general reflections on authoritarianism and do not mention Erdogan by name, with the exception of one that uses the president's initials and describes him as lacking principles and contradicting himself). In addition to the criminal proceedings, the Higher Education Council, or YOK -- the governmental body that oversees Turkey’s universities -- questioned Caliskan about his Twitter activity last fall.

“What we now see is the preparation for making Turkey a full authoritarian country, and for this the governing party and President Erdogan need complete silence on behalf of civil society, academics, journalists and other learned men and women,” said Caliskan, who researches political parties, democratization and authoritarianism. “That’s why I believe they are attacking academic freedoms and freedom of expression on an unprecedented scale.”

“Turkish academia, long considered among conservative circles to be a bastion of secular, modern and antireligion intelligentsia, is being overhauled,” A. Kadir Yildirim, a research scholar at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, wrote in an editorial in The Washington Post. “The administrators are fully compliant with the demands of the political top brass. Likewise, faculty in most universities internalized the extraordinary influence Erdogan and his cadres exert over virtually all aspects of life in Turkey and fall in line accordingly. Erdogan’s attack on the petition-signing scholars is not about the content of the petition. It primarily aims to domesticate the remaining oppositional voices within the academia.”

“Until recently, academia was not directly under attack,” Yildirim said in an interview via email. “Although there has been an increasing co-optation of academics by the AKP [Justice and Development Party] government over time, the latest attack was a clear sign that little will be tolerated on public and collective criticism of the government and President Erdogan.”

In a statement issued in January, reported by the independent press agency Bianet, the Higher Education Council suggested that the petition fell outside the bounds of protected speech and accused the signatories of supporting terrorism.

“This statement backing terrorism cannot be associated with academic independence,” the statement said. “Ensuring security of our citizens is the most basic duty of state. What is necessary as to this statement will be done. We will meet with our university presidents and intercollegiate Council to discuss this issue.” YOK did not return multiple email messages requesting an interview.

A counterpetition signed by more than 2,000 academics similarly accuses the signatories of the peace petition of betraying the state. “A group of so-called academics, which have taken every opportunity to unblushingly besmirch the Republic of Turkey in order to defame and insult it while hiding behind deceitful lies, have accused our state of committing torture and massacre. In spite of this, the same group of so-called academics … does not even mention innocent babies murdered, children left without parents and orphaned, soldiers or policemen martyred or injured, the historical, national and religious treasure that have been burned and destroyed by the terrorist organization,” says the counterpetition (in translation).

“Our country, experiencing the treacherous terrorism committed by the PKK for nearly forty years, unfortunately, has not only been exposed to bullets of this reprehensible organization, but also it has been attacked by the so-called academics, who are educated by the state so that they contribute to the scientific and technological development of our country. Their present attitudes and expressions are more dangerous and contemptible than the bullets shot by the bandits in the mountains … We believe that this petition, which lacks any academic and humanitarian concern, has only one purpose, which is to hinder the fight against terrorism and demoralize our security forces …”

In a December report on the conflict in southeastern Turkey between the military and militants associated with the PKK, Human Rights Watch documented cases in which Kurdish civilians have been injured or killed and raised concerns about state-imposed curfews that have left “populations of entire neighborhoods” without access to food, water or electricity.

Ebru Erdem-Akcay, an independent scholar and U.S.-based political scientist who researches Turkey, said the academics who signed the peace petition have been unfairly criticized for their choice to condemn the actions of the Turkish state and not those of the PKK. A terrorist organization by definition is not accountable to anyone, she said, whereas the government is. “We hold them as the party who holds the power to do anything to start negotiations, to be more careful about who they are attacking,” she said.

Erdem-Akcay has been monitoring the repercussions on academics who signed the petition have faced so far. “There are a total of about 2,000 people who signed the peace petition in two waves,” she said. "Some of them are not facing any disciplinary investigations at their universities at this point. For some others, especially those in provincial universities -- I think those are the people who are most at risk -- they will likely end up with some kind of punishment. It could range from a simple warning to them losing their jobs, and if they lose their jobs they will not be able to find academic careers in Turkey again.”

As for the Istanbul prosecutor's investigation of the 1,128 initial signatories, “there are no developments on that front yet,” Erdem-Akcay said. “Some say that the local prosecutors will defer the case to the higher prosecution office, being Istanbul, and all of the scholars will be tried together. Nobody knows whether the second wave of signatories will be brought in under that case.”

Beyond the various criminal and administrative charges, some academics who signed the petition say they feel they are in danger. “I am being targeted by the irresponsible and unethical propaganda news of the AKP-supported media,” Mine Gencel Bek, a professor of journalism at Ankara University, said over email. “Some TV channels, websites and newspapers targeted us by labeling [us] ‘terrorist professors.’ I received several insulting and threatening messages following that so-called news.”

Bek said that signatories fear their lives are in danger “as a result of these negative publications.”

“The anti-intellectual sentiment is extremely high and the government is feeding it unbelievably,” said Demirer, the political scientist from Kocaeli University.

Demirer, who since his brief detention has left Turkey for a sabbatical at Villanova University, in Pennsylvania, said he is not as worried about risks to him personally as he is about his younger colleagues at earlier stages in their careers. And he is worried about the future of the university system in Turkey.

“There is a growing tension between left-wing scholars and the government,” said Baris Unlu, an assistant professor of political science at Ankara University who was acquitted last week on criminal charges of disseminating terrorist propaganda and praising “crime and criminals” in relation to an exam question he wrote asking students in a Political Life and Institutions in Turkey class to compare two texts written by Abdullah Ocalan, the PKK leader.

“As the government has become more authoritarian and corrupt, it has managed to oppress two separate fields which are supposed to, though in different ways, speak the truth: the judiciary and the media,” Unlu said via email. “Today, both the judiciary and media have lost their independence almost entirely. So the universities that are still somewhat autonomous are the only spheres that are home to persons who consider the intellectual activity of speaking the truth their moral and occupational duty. But the problem is that the government cannot tolerate truth anymore, for the simple reason that authoritarianism and corruption cannot tolerate truth. Plus, as the government loses its intellectual legitimacy, meaning that not even one serious intellectual in Turkey and in the world can support such a government without losing her/his reputation, it resorts to violence or the threat of violence more and more. This is the fundamental reason, I believe, behind the current attacks on scholars. And this tension will likely grow in the foreseeable future.”