You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Colleges are feeling heat to prove that their students are learning. As a result, a growing number of colleges are measuring intended “learning outcomes” as well as issuing grades. But fewer are using standardized tests than was the case a few years ago.

Those are findings of a new survey from the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U). The liberal education organization received responses from chief academic officers at 325 of its member institutions, including community colleges and four-year institutions (public and private as well as a couple of for-profits).

Almost all respondents said their institutions either assess student learning outcomes across the curriculum (87 percent) or plan to do so (11 percent). The remaining 2 percent may have a problem with their regional accreditors, which require colleges to measure learning this way.

Those percentages have increased compared to previous surveys by the association. In 2009, for example, 72 percent of chief academic officers said they assessed outcomes across the curriculum.

Accreditors deserve some credit for that change, said Debra Humphreys, AAC&U’s senior vice president for academic planning and public engagement.

“If they had not been pushing,” she said, “these numbers would not be like this.”

Fully 85 percent of institutions said they have a common set of intended learning outcomes for all their undergraduate students in place, according to the survey, which was conducted by Hart Research. That number is up from 78 percent in 2008. Two-thirds said they assess learning outcomes in general education, which is also a big increase. And 63 percent are assessing at both the department level and in general education.

Given that momentum, it might surprise some that the group’s members appear to be moving away from standardized tests, which is one way to track student learning.

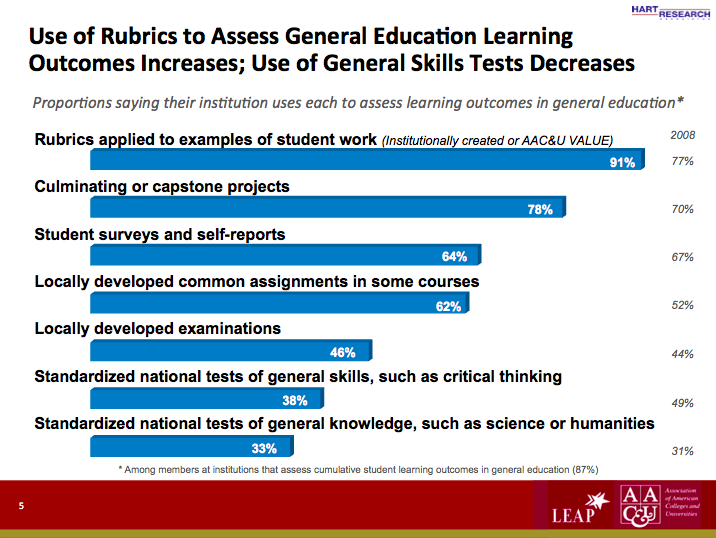

Among institutions that assess outcomes in general education programs of study, 38 percent of respondents said their institutions use standardized national tests of general skills, such as critical thinking. That’s down from 49 percent in 2008.

Two testing firms, however, reported solid demand for their assessments of general skills.

One reason for that declining interest, Humphreys said, might be that standardized tests do not provide enough information for colleges to try to make improvements to their curricula.

“Even if you take it seriously, it doesn’t tell you enough to do much,” she said. “It’s hard to know what to do with that data.”

Instead, colleges increasingly are shifting to assessments that are based on students’ work in the classrooms, the group found.

For example, 91 percent of those who assess in general education use rubrics, applying them to examples of student work. In 2008, that number was 77 percent. Other common approaches are the use of capstone projects (78 percent), student surveys (64 percent), locally developed common assignments (62) and locally developed examinations (46 percent).

The association said faculty members tend to prefer those tools -- including rubrics the faculty design themselves -- compared to standardized tests from national firms.

“The good news from this new study is that higher education now is using assessment tools designed to help faculty and institutions tackle, target and solve the chronic problem of weak student performance on these essential learning outcomes,” said Carol Geary Schneider, the group’s president, in a written statement. “The assessment shift from tests that were disconnected by design from students’ course of study toward assessment tools that are anchored directly in students’ assignments across the curriculum is a huge cultural shift.”

To Test or Not

Many of the group’s members use both standardized tests and faculty-developed rubrics. And two nonprofit testing organizations that offer assessments of general skills said demand for those tests remains strong.

Since 2002, the Council for Aid to Education has been measuring undergraduate student learning with its Collegiate Learning Assessment, which recently was updated and is now the CLA+.

Roger Benjamin, the council’s president, said the assessment has seen annual increases of 10-20 percent in the number of students who take it in recent years. But he acknowledged some sluggishness.

“We’re not growing as rapidly as we were three or four years ago,” Benjamin said.

However, Benjamin said the test has proven valuable in evaluating the efficacy of promising innovations in higher education, such as competency-based education or the City University of New York’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs.

Education Testing Service has not seen any decline in demand for its general-education assessments, said David Payne, vice president and CEO of the firm’s global education division.

“In fact, our own research shows an increased interest in using standardized assessments, like HEIghten, for example, to measure general education student learning outcomes,” he said in a written statement. “With ever-increasing pressure on higher education to demonstrate its value, proactive institutions are using assessments as tools to inform learning improvements and overall institutional effectiveness.”

AAC&U in 2010 released its own rubrics as part of its Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education initiative. The group found that 42 percent of respondents’ institutions use those assessments. Those that do tend to use rubrics for assessing critical thinking, written communications, quantitative literacy and oral communications.

In addition, among colleges that use rubrics that were developed at their institutions, 58 percent said AAC&U’s rubrics helped inform their development.

The results show a “growing sophistication,” said Humphreys. “People are finding the rubrics more useful.”

Colleges also appear to agree, for the most part, on which broad skills and knowledge areas to assess student learning. The association found a majority of respondents have common sets of learning outcomes in 18 of 22 surveyed areas.

Benjamin applauded the group for its work to encourage colleges to use “value rubrics,” or assessments based in student work, including the Lumina Foundation-led Degree Qualifications Profile.

“They help faculty focus on how to figure out the teaching and learning in the classroom,” he said.

Assessment of learning outcomes isn’t going away, said Humphreys. And if higher education doesn’t continue to step up its game, she said, lawmakers will push different ways to try to ensure the value of a college degree. That’s likely to end poorly, as Humphreys said the U.S. Congress will use proxies -- such as graduates’ income levels -- that don’t measure learning.