You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Kansas State University

In the past five years, the five wealthiest National Collegiate Athletic Association conferences have undergone some significant changes. Chasing more exposure and money, conferences have realigned and the 65 institutions making up the leagues known as the Power Five successfully fought for a greater level of autonomy, allowing them to vote on several rule changes without involving the other members of Division I.

But at least one thing hasn’t changed: racial inequity in academic success among the powerhouse football and men’s basketball conferences.

Just over half of black male athletes graduate within six years, compared to 68 percent of athletes overall and 75 percent of undergraduates overall, according to a new report from the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education. The gaps are comparable to when the center conducted a similar study in 2012.

“The landscape has changed in those years, but the trends are the same,” Shaun Harper, the center’s executive director, said. “There’s been a slight increase in graduation rates, about three percentage points, but it’s been across the board, so that doesn’t narrow the racial equity gaps. That increase is perhaps good news for universities, but the racial disparity still remains.”

And the gaps remain even though many a university president or coach talks about athletics as a means of providing an education, not just a chance to play, and even though athletes have access to tutors and various programs to help them academically.

Two-thirds of those institutions graduated black male athletes at rates lower than black men who were not athletes. Just one institution -- Northwestern University -- graduated black male athletes at a rate higher than or equal to undergraduate students overall.

At Northwestern, black athletes had a 94 percent graduation rate, compared to 90 percent for all athletes and 88 percent for black men. It’s the same rate as the overall rate for undergraduates. Stanford University had similarly high graduation rates, but black athletes still lagged behind other athletes and undergraduates by six percentage points.

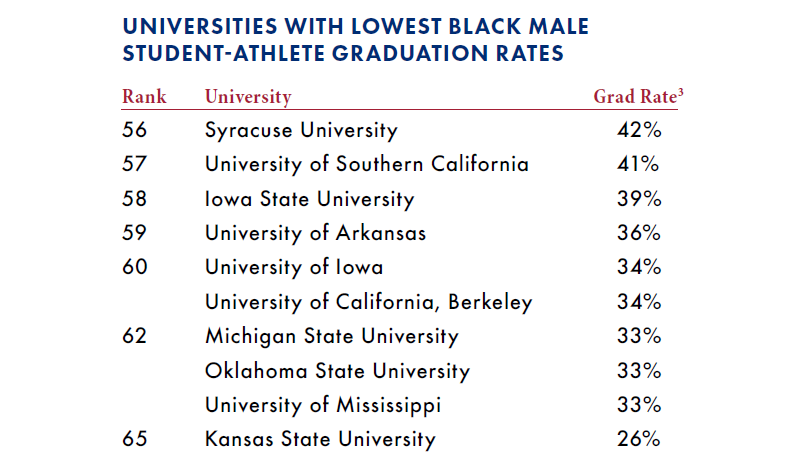

The study found that Kansas State University had the lowest graduation rate for black male athletes in all 65 institutions. Only 26 percent of Kansas State’s black athletes graduate in six years, compared to 63 percent of all athletes. The rate, however, is the same as all black men on campus. At Michigan State University, 33 percent of black male athletes graduate in six years, compared to 70 percent of all athletes, 55 percent of all black men and 78 percent of all undergraduates. Neither institution replied to requests for comment.

A spokeswoman for the National Collegiate Athletic Association noted that the federal graduation rate used in the study does not account for students who transfer. When the NCAA's metric, the Graduation Success Rate, is used, graduation rates for all athletes are much higher, though the NCAA's method also has its critics.

Harper said it’s time that black athletes and their families start demanding that colleges take more seriously the academic pursuits of black male athletes. Too many athletes go to college believing it’s a path to playing their sport professionally, Harper said, when less than 2 percent of NCAA basketball and football players go on to play in the NBA or NFL.

“There’s that classic story of the coach going to a single mother’s home and sitting in her living room, telling her how he’s going to take good care of her son,” Harper said. “I think we have to do a better job of equipping parents and families with the kinds of questions they should be asking in that moment. Once on campus, athletes literally control billions of dollars; they could use that power to demand institutions do a better job of getting them resources and support. This is a system that creates billions of dollars, and it’s white men who are profiting most from the backs of these black players.”

The study also identifies concerns about racial inequities in leadership positions. While the majority of revenue-generating athletes are black, only 16 percent of head coaches are black men. About 15 percent of athletics directors are black men. None of the five commissioners are black.

On the other side of the spectrum, though no less troubling, Harper said, is how vastly overrepresented black men are on basketball and football teams compared to the “disgracefully small number of black male students in the undergraduate population.”

During the 2014-15 academic year, black men at these institutions accounted for about 2.5 percent of undergraduates, but 56 percent of football players and more than 60 percent of men’s basketball players were black. At Auburn University, 78 percent of basketball and football players are black, but black men account for just over 3 percent of undergraduates.

“I’m not suggesting that athletics departments should award fewer scholarships to talented black male student athletes,” Harper said. “But these are campuses where admissions officers and others often say that qualified black men cannot be found. Yet they can find these students when they want them to play football or basketball. They go far and wide to find them. Colleges should spend that same level of energy on finding nonathletes.”