You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

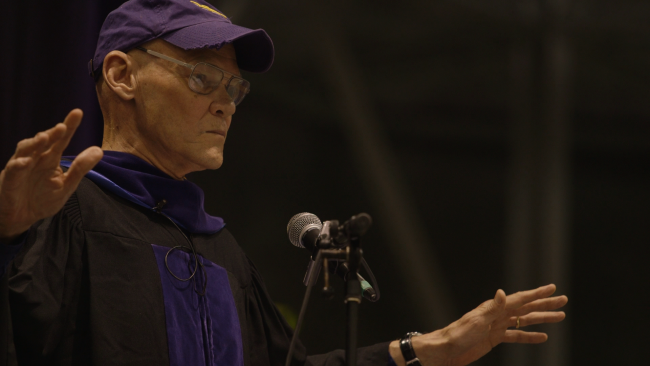

James Carville speaks about the ideological shifts in higher education funding.

Starving the Beast

Starving the Beast opens with James Carville, a well-known Democratic strategist, standing behind a microphone at Louisiana State University.

“They say,” he tells the crowd, “education is a commodity.”

By “they,” Carville means the reformers -- an assortment of politicians, think-tank leaders and university administrators -- who believe that colleges should operate like businesses. That like any other good or service, a college education has a price. “It’s a barrel of oil, it’s an ounce of gold, it’s a stock,” he says. “It’s anything.”

The documentary, directed by Steve Mims, premiered this weekend at the South by Southwest film festival in Austin, Tex. Clocking in at 95 minutes, it explores the decline of state funding and the philosophical divide that’s caused it: What kind of a good is higher education? What should taxpayers be expected to support?

“Focusing on the root of it,” Mims said, “that's the real story.”

The film lays out an overview of the debate’s philosophical underpinnings: originally, states saw public colleges as a worthwhile investment in their residents. Poor students could gain useful skills and move up in the world while also contributing to their states’ economies. In the early days of public higher education systems, many states charged little if any tuition.

On the other side, there are the reformers and think-tank leaders, the antispending politicians and political operatives, the Bobby Jindals and Grover Norquists. Reformers like Norquist -- founder of Americans for Tax Reform, which famously encourages lawmakers to pledge their support for low taxes -- say that public colleges are wasteful, and lawmakers feel an obligation to keep taxes low. The idea, Mims said, “is that the system is broken. That it’s too expensive, and it has to be fixed.”

For reformers, that means everything from cutting funding to gutting protections that don't exist in other businesses, like tenure.

"Tenure, as utilized by public higher education, is outdated," Wallace Hall, a regent at the University of Texas System, says in the film. "It’s almost universally reviled, and it’s in desperate need of a competitive alternative."

While Mims interviewed several conservative reformers for the film, Hall thought the final production had a liberal bias, according to the director. "He thought the film was somewhat slanted in a particular direction," Mims said.

But the goal, he added, was to let advocates on both sides speak without interruption. "If you understand the philosophy of the people on both sides of this argument, then everything else flows from that."

The film starts in Texas, where former governor Rick Perry -- who appointed Hall -- was trying to make a series of policy changes. Created by the think-tank leader Jeff Sandefer, the reforms were designed to treat colleges more like businesses. Sandefer suggested paying professors based on measures like student evaluations and creating a voucher system that would put money in the hands of students rather than colleges.

“They were so simple,” Sandefer says in the film, “that anybody who ran organizations would look at them and go, ‘Well, of course.’”

In a similar effort, Texas A&M created the “red and black report,” which chronicled how much money each professor brought into the university.

Originally, Mims focused the project on Texas. He's an adjunct at the University of Texas at Austin, and for years he had watched the cry for reform at Texas’s public colleges gain traction. Along with producer Bill Banowsky, he began filming committee meetings and sit-down interviews. But as they continued their research, they saw parallel situations playing out across the country.

Louisiana. North Carolina. Virginia. Wisconsin. “It just became more and more complicated,” he said. In its final version, the film chronicles tensions in all five states.

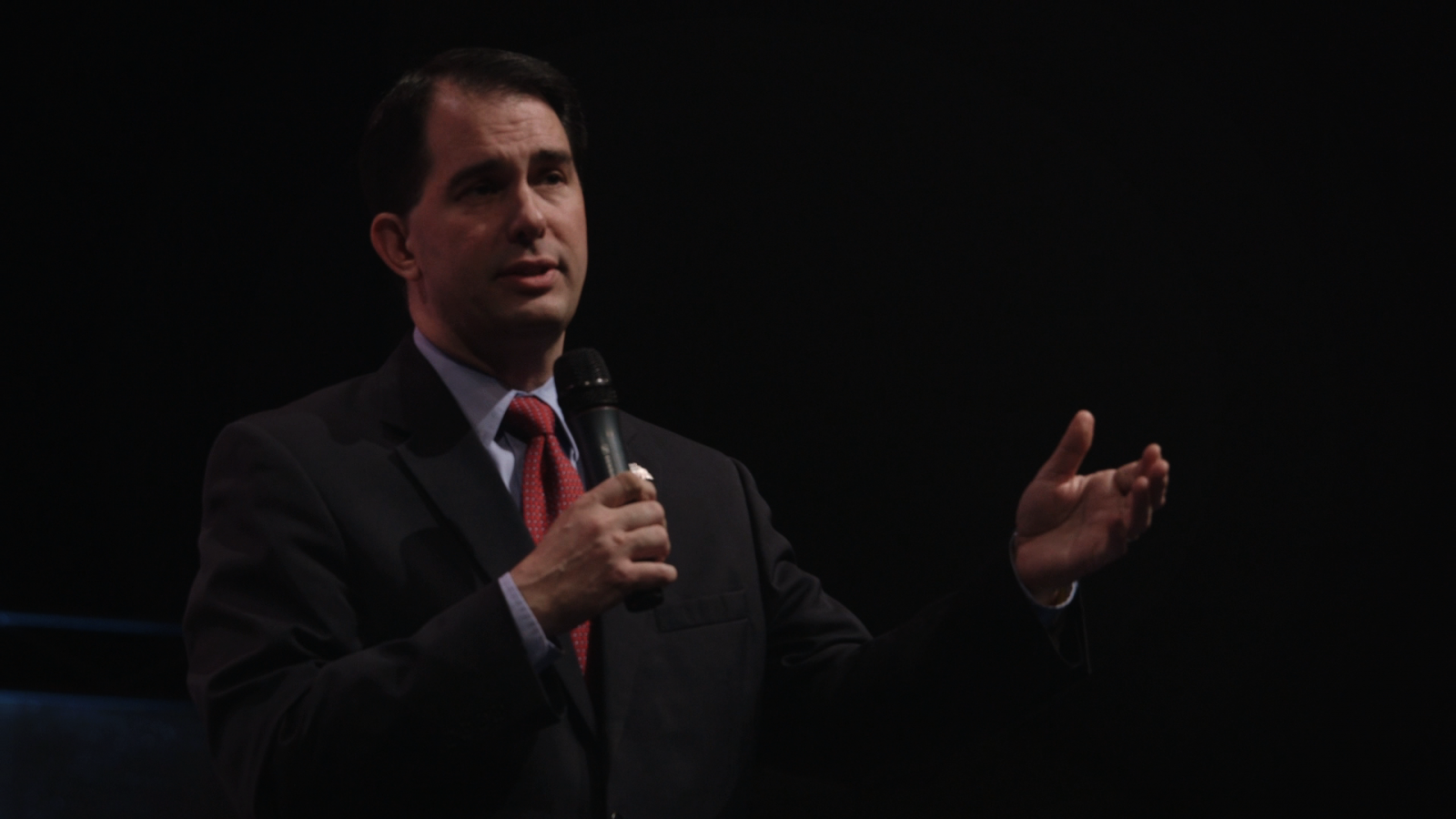

In Wisconsin, Governor Scott Walker cut millions from state colleges and universities last year. When he submitted a draft of his budget, he also removed some language from the state university system’s mission, including the charge that universities “search for truth” and “improve the human condition.” He quickly called the changes a “drafting error,” but his opponents say the mistake signaled a philosophical shift.

In Louisiana, public colleges faced massive cuts last year, prompting the president of Louisiana State to consider financial exigency. This year, Louisiana colleges face many of the same problems.

In North Carolina, conservative leaders shut down University of North Carolina centers for poverty, biodiversity, and civic engagement and social change, a move that opponents argued was an attack on academic freedom.

The University of Virginia is the only story in the film that doesn’t quite fit the narrative: the university’s governing board decided to remove President Teresa Sullivan back in 2012, arguing that her approach wasn’t innovative or businesslike enough.

But after three weeks of protests, Sullivan was reinstated. It was, for Sullivan’s supporters, a victory for the institution’s core values, and a victory over a conservative reform agenda.

“The UVa story,” Mims said, “it’s the one that sort of has a happy ending.”

For now, Starving the Beast will follow the states it profiles: it will screen at Louisiana State University in April and a few days later at the Wisconsin Film Festival. Beyond that, Mims is still developing a release strategy.

As the film gains a wider audience, Mims hopes it will help shed light on what he says is one of the nation's least understood problems. While many of the academics interviewed were up-to-date on the struggles in their own state -- "they know their little part of it" -- they seemed unaware of the problem's scale.

But Mims is hopeful that the pushback to the reform agenda will help turn the issue into a mainstream public debate. “Part of what made this worthy of being a film is this resistance,” Mims said. Without the resistance, without the drama, “change happens at a university, and it's pretty invisible.”