You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Education Advisory Board

What can higher education learn from the health care industry?

The two sectors have vastly different goals: one educates people, the other keeps them alive. But both colleges and hospitals face some of the same pressures. As the baby boom generation ages and enters retirement, care providers are bracing for the strain that surge of demand will place on the health care system. Similarly, colleges and universities are expecting to enroll more students from lower income brackets, which will create new demands for their advising services.

“It becomes an efficiency issue,” said Ed Venit, a senior director at the Education Advisory Board, based in Washington, D.C. “How thin are we going to spread ourselves? If we’re unable to provide adequate care for these students, our outcomes will fall.”

Research by the EAB suggests both health care and higher education can tackle those challenges by following the same approach. It’s a strategy known as population health management, which involves using predictive analytics to break populations into smaller groups by risk and assigning different support services to each group. And the handful of colleges that have begun to organize their advising services by those principles are already seeing encouraging gains in student retention.

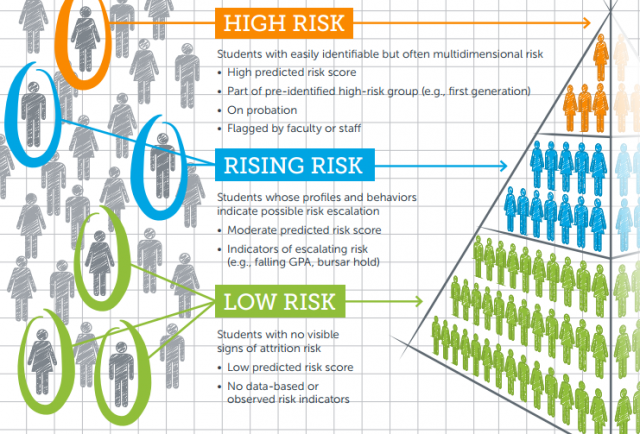

The theory of population health management has been in development for about a decade but is only now being considered in higher education. To adapt it to a college setting, Venit said, institutions need to do four things: identify the factors that determine if a student belongs to the low-, medium- or high-risk group; come up with support strategies for each group; find a software platform that lets advisers, tutors and others monitor students; and assign responsibility for student success.

“No one school has all of this in place,” Venit said. But because of the interest colleges are showing in analytics, he said, “We are now in a position where the groundwork has been laid to do steps two, three and four.”

Who’s at Risk?

In health care, according to the population health management theory, about 70 percent of people are categorized as low risk. Adapted to higher education, these are the students that are on track to graduate on time and in many cases only need self-service portals and automated notifications to progress.

Another 25 percent are considered medium or rising risk. “I use diabetics as an example,” Venit said. “This is someone with an identifiable condition. They might not be sick today, but they might have trouble in the future.”

In higher education, Venit said, rising-risk students may be those who haven’t completed their financial aid application, received a low midterm grade or have yet to register for the next term but are still enrolled and attending classes. “You want to catch problems before they escalate and nip them in the bud,” he said.

Finally, there are high-risk individuals, who make up about 5 percent of the population. To serve those people, care providers and colleges need to surround them with specialists.

Venit stressed that, unlike in health care, colleges themselves need to look at their student populations and design the system to suit their needs. Elite institutions likely have different makeups of low-, medium- and high-risk students than regional public universities. Other colleges may tweak the system where even a student with a perfect GPA who doesn’t intend to graduate from that institution could be considered high risk.

There are also aspects of population health management that are a poor fit for higher education. Some hospitals are experimenting with new models where they are compensated based on the total number of patients that they treat, as opposed to the number of treatments. Higher education, Venit said, will have to find a different way to restructure itself to instill accountability and ownership of student retention and outcomes in the right people.

“We’re not trying to drop whole cloth a health-care strategy on higher education,” Venit said. “We’re using it as a starting point, an inspiration.”

Real Numbers, Real Students

Middle Tennessee State University started following the population health management principles in fall 2014. One year later, the university is seeing its retention rates tick up. In the College of Liberal Arts, for example, fall-to-spring retention for first-time freshmen and sophomores this academic year surpassed 90 percent, an increase of 3.4 percentage points compared to 2014-15. The university’s average freshman retention rate is 70 percent.

Administrators at MTSU said they recognized a need to change its advising strategy after realizing that about 70 percent of freshmen who earned a grade point average below a 2.0 did not return for a second year -- about 420 students a cohort. The data also showed that many of the students who earned a GPA between 2.0 and 3.0 in their first year did not graduate.

“All of a sudden we’re talking about real numbers,” Richard D. Sluder, vice provost for student success, said in an interview.

MTSU is a member of the Student Success Collaborative, a group of colleges and universities working on improving student outcomes organized by the EAB. Membership in the collaborative gives colleges access to a data analytics platform, best practices research and consultants.

In addition to joining the collaborative, MTSU also reorganized its academic advising structure. The university two years ago hired 47 new advisers, splitting them between majors to achieve an overall student-to-adviser ratio of about 300 to one. Each college has its own advising manager, who reports to Sluder and the college’s dean.

“When you’ve got those ratios, what you can do is use analytics … so that advisers can focus on those students where the biggest gains can be made,” Sluder said. “Looking at freshmen who are at less than a 2.0 [GPA], that’s a ripe group for doing improvements with.”

Lucy Langworthy, advising manager for the College of Liberal Arts, credited the new advisers for the improvements the university has seen so far.

“A lot of schools aren’t as fortunate in that they can’t purchase software and hire all those people at once,” Langworthy said in an interview. “We have enough advisers to really give students some time when they come in.”

Langworthy said the university “ideally” wants advisers to spend 70 percent of their time with high-risk students, but added that it is only an estimate. Many of the students who need face-to-face advising the most don’t always show up, she said. Still, she said she was optimistic about advisers’ ability to reach medium-risk students.

MTSU uses academic performance as the main factor determining student risk. If a student declares a major but doesn’t enroll in key courses, takes course sequences in the wrong order or earns a low grade in an important major requirement, the system flags it.

The university loosely follows the 70-25-5 breakdown between risk groups, Sluder said, but it is also devoting attention to specific groups of students -- in particular, freshmen, sophomores, transfer students and students with more than 90 credits who have stopped out. During lulls that occur during the semester when advising is in low demand, the university’s advisers conduct campaigns to target those groups to ensure students are on track to continue their studies.