You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

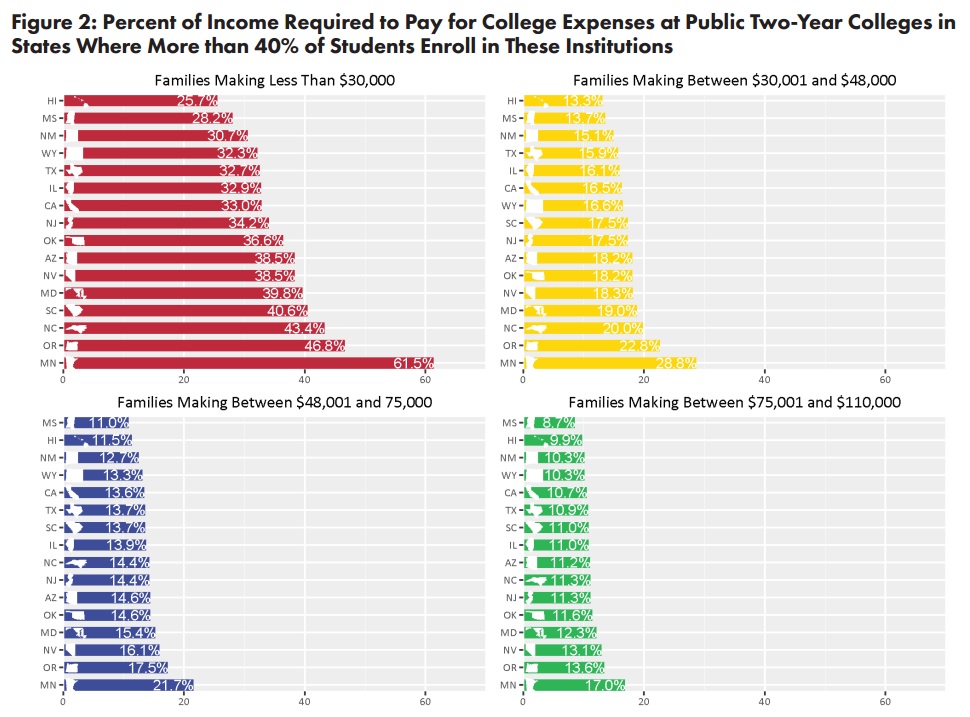

Overall college affordability has worsened in 45 U.S. states since 2008, creating a significant financial burden for students of modest economic means.

That’s the top-line finding in a new, state-by-state study by researchers from the Institute for Research on Higher Education at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education, Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College of Education and Human Development, and the Higher Education Policy Institute.

The report defines affordability as reasonable estimates of the total educational expenses for students and families in each state, calculated as a percentage of family income. Educational expenses include tuition and costs of living, minus all grant-based financial aid from federal and state governments and institutions.

Students who lack wealth have been hit hardest, the study found, as college has become less affordable since the Great Recession began.

“This study shows how the deck is stacked against low- and middle-income Americans when it comes to paying for college,” Joni E. Finney, one of the study’s co-authors and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, said in a written statement. “Without policy changes, the data point toward a problem that will only worsen. That paints a bleak picture for millions of Americans.”

Even the best-performing states tend to have a college affordability problem, the report found.

Only 15 states improved on affordability measures for community colleges between 2008 and 2013, meaning families in these states would pay a smaller portion of their income, on average, for students to attend full time.

Likewise, the report, which is based on federal data, found public, four-year institutions in just six states became more affordable during that period. Seven states saw an improvement on measures of affordability in the private nonprofit college sector. (Click here for an interactive map of the report’s findings.)

One reason for the problem, according to the study, is that much of state financial aid is not based on financial need.

For example, average state financial aid received for reasons other than financial need at public institutions -- such as merit aid -- increased from $189 per student in 2004 to $268 per student in 2013, after adjusting for inflation, the report found.

In addition, the amount of state financial aid flowing to high-income students at public four-year institutions increased by more than 450 percent between 1996 and 2012, wrote Will Doyle, a professor at Vanderbilt and one of the report’s co-authors.

“State leaders can craft policies that ensure everyone who can benefit from college can go,” Doyle said in a written statement, “but in too many states they have allowed college costs to rise beyond the reach of families.”

Another affordability challenge is that full-time students increasingly cannot pay their way through college by working, even at community colleges. And low- and middle-income families often must weigh the trade-offs between attending college and getting a job, a problem exacerbated by stagnant household incomes over the last decade.

That all means loans increasingly fill the gap between educational expenses and what students get in financial aid, according to the report -- a serious concern, particularly for less wealthy students.

“Unless state and federal policy makers act together to ensure that educational opportunities beyond high school are affordable,” the report concludes, “it would not be surprising to see greater economic and racial stratification reflected in our colleges and universities -- as well as society.”