You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

“This is my freshman year at Spelman College,” the tweet read. “And my last year, because I decided to leave after what happened to me.”

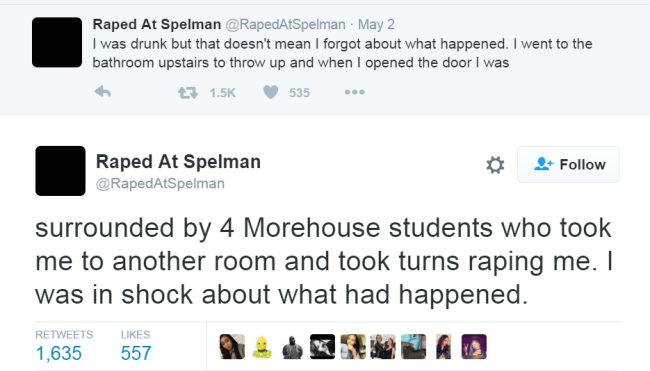

The message, shared anonymously last week under the Twitter handle @RapedAtSpelman, was the first of a series of tweets detailing an alleged gang rape at the historically black women’s college. The student said she was sexually assaulted by four students from Morehouse College, a nearby all-male HBCU with strong historical ties to Spelman, and when she tried reporting the crime to campus officials, she was met with indifference and hostility.

The series of tweets, which prompted pledges from Spelman and Morehouse to investigate the allegations and review their sexual assault policies, was just the latest example of students turning to social media in recent months to air their dissatisfaction with how cases of campus sexual assault are handled.

“There’s a sense that the university adjudication system doesn’t often work, and that the criminal system is decades behind that,” said Andrea Pino, director of policy and support of End Rape on Campus. “Oftentimes there really are no other options, or survivors have exhausted what options they have. Social media is sometimes the only choice they have at seeking some kind of justice.”

Earlier this week, Marshall University promised to review its sexual assault policies after students used Twitter to criticize its handling of a sexual assault complaint. The posts accused the university of endangering a victim’s safety by reinstating a student who had been indicted for sexually assaulting her. In April, Kenyon College ordered a similar review of how it handles sexual assault allegations, after a former student posted an essay on his blog and Facebook page.

In the widely shared essay, Michael Hayes criticized Kenyon for not punishing a student who had allegedly sexually assaulted his younger sister. His sister, who identifies as a lesbian, said she was raped by a male student while falling in and out of consciousness after consuming a combination of wine and prescription medication.

“Despite her documented injuries, a bed stained with her own blood, her sexual orientation, and the combination of that much alcohol and prescription medication in her body, the college concluded -- both initially and on appeal -- that there was insufficient evidence to conclude that it was more likely than not that the college's policy on sexual assault had been broken at all," Hayes wrote. “Kenyon failed my little sister in a way that I, with her permission, refuse to be silent about.”

In March, Howard University announced it would update some of its polices, including conducting background checks on all student employees, after students used the Twitter hashtag #TakeBackTheNightHU to protest the university’s handling of sexual assault. The hashtag was inspired by a Howard student who tweeted that she had been sexually assaulted in her dorm room in October, but that her alleged attacker, then a residence hall adviser at Howard, remained on campus.

Another student soon tweeted that she, too, had been assaulted by the same man in February. Police reports were filed in both instances. No charges were filed in the October case, and the investigation into the allegations from February remains open. The accused student is still enrolled at Howard but is no longer a resident assistant.

“I think part of this is that the regular routes aren’t working, but it’s also about being heard,” Eric Stoller, a student affairs consultant who is also a blogger for Inside Higher Ed, said. “It can be about the amplification effect of Twitter. You send out a single tweet, include a hashtag and your cry for help is available to a greater audience that exists outside the boundaries of your campus. As a lever of change, that’s important.”

The tweets written by @RapedAtSpelman have so far received more than 19,000 retweets. Thousands of tweets have made use of the hashtags #TakeBackTheNightHU and #RapedByMorehouse. The Facebook post about the assault at Kenyon has been shared more than 900 times.

Meanwhile, students remain hesitant to report incidents of sexual violence to campus officials and law enforcement. According to a survey of 27 institutions conducted by the Association of American Universities last year, less than 28 percent of victims reported being assaulted to any organization or agency.

Only half of female undergraduates said they thought their university would take their report “very” or “extremely seriously.” Of those that did not report their assaults, 30 percent of undergraduate women who had been raped said they thought nothing would be done and 15 percent said they did not think anyone would believe them. Nearly 40 percent said they felt too embarrassed or ashamed.

“For some students, social media can be a form of catharsis,” Stoller said. “There’s pent-up angst and anger and emotion, and people need an outlet. Institutions can’t engage with everybody who’s tweeting away with the hashtag, but it’s good to at least have a statement saying, ‘We’re listening and this is what we’re doing.’”

While the colleges at the center of the recent social media campaigns have responded quickly to the tweets and Facebook posts, they have also expressed apprehension about discussing such a delicate issue over social media.

Morehouse's president, John Silvanus Wilson, Jr., said the tweets were the first the college had heard of the allegations. Calling the tweets "disturbing," Spelman's president, Mary Schmidt Campbell, noted that the anonymous nature of the comments made it difficult to get in touch with the student and offer help.

In March, Howard officials said they were concerned about using Twitter to discuss the outcome of a case that was still being investigated.

“We are and have been investigating all reports that have been made to us,” the university said in a statement. “These cases cannot be adjudicated through social media without compromising the integrity of the investigation.”

Pino, of End Rape on Campus, also said there are some pitfalls to students using social media to publicize their experiences with campus sexual assault. Tweeting about being raped or sexually assaulted can invite harassment and other kinds of cyberbullying, further harming the victim. At the same time, she said, “social media has been the backbone” of the current movement to hold colleges more accountable when they mishandle cases of sexual assault.

“Students are able to learn that this is happening everywhere and that there are others coming forward as well,” Pino said. “There’s this rise in accessible solidarity. You don’t have to have people on campus helping you. You have people all around the world that can help you.”