You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Waiting in lines at the polls, some of them are there, but most of them aren’t: College students just aren’t voting. In the 2012 elections, only 45 percent of them cast a ballot.

But that number doesn’t tell the whole story, and certain groups of college students are voting at much higher rates than others, according to a new study from Tufts University’s Institute for Democracy & Higher Education.

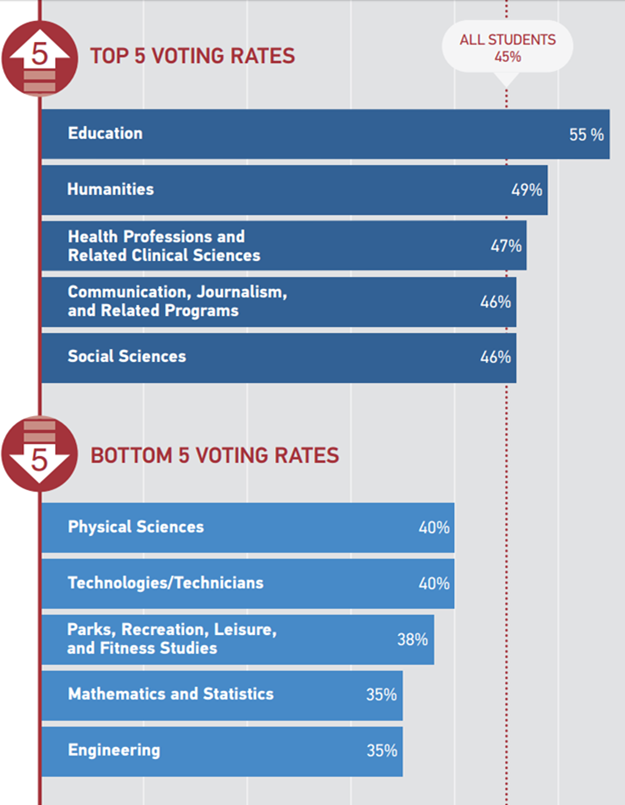

Voting behavior varies widely among college majors, the researchers found. Students in STEM fields were less likely than their peers to vote -- and across all disciplines, engineering and math majors (at 35 percent) were the least likely to vote.

Forty-nine percent of humanities majors voted, with health, communications and social sciences majors following close behind. But while they all voted at above-average rates, only one major broke 50 percent.

“When I talk to groups and I ask, ‘What do you think the highest voting rate in the country is?’ everything says, ‘Oh, political science or sociology,’” said Nancy Thomas, director of the institute. “Well, it isn't. It’s education.”

Education majors voted at 55 percent in 2012 -- higher than any other discipline. They beat the engineering and math students by a 20-point margin.

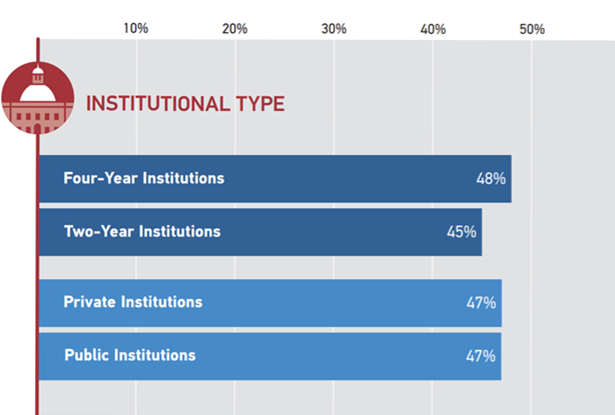

Voter turnout also varies by region. Students in the Southwest voted the least (39 percent), while students in the Plains voted the most (55 percent). Four-year institutions scored slightly higher than two-year institutions, while the numbers were the same for privates and publics.

The researcher analyzed the voting records of 7.4 million students at over 780 institutions. To get the data, they formed a partnership with the National Student Clearinghouse, which collects enrollment records. For colleges that opted in to the study, the Clearinghouse combined enrollment records and public voting records, collected by the company Catalist, and sent the researchers the results.

After running the numbers, the researchers identified outliers: campuses with voting rates that were considerably higher than predicted -- or considerably lower than predicted. They visited six high-scoring outliers, two low-scoring outliers, and one in the middle. (They wanted to visit more low-scoring campuses, but: “We have to call them up and say, ‘Your voting rates are pretty terrible. Can we come and find out why?’"

At the high-scoring colleges, students from all disciplines were much more engaged in political life. The chemistry club would run a blood drive. STEM professors would encourage political discourse in the classroom.

And that, Thomas said, is what matters: Students are more likely to vote when they’re encouraged everywhere to engage in political discourse, when political dialogue seeps into the nooks and crannies of campus life.

On the other hand, students who don’t talk about politics on campus may not feel compelled to participate in politics on election day. As a result, entire disciplines get left behind. And eventually, Thomas reasons, that could mean fewer politicians with a background in the sciences -- which could affect things like research funding or climate-change legislation.

“It's not only that they aren't picking their officials,” she said. “They are literally invisible to their officials.”

With the 2016 election on the horizon, Thomas said the findings point to strategies for colleges who want to teach their students to be more civically engaged.

One of the most important of those strategies: “Talk politics, and do it in the disciplines where you wouldn't think to do it,” she said. “Every discipline -- every single one -- has public relevance."