You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A new report looks at endowment spending on low-income students at wealthy institutions.

The Education Trust

A fraction of a percentage point can translate into a lot of money.

And a change that small in universities' endowment spending could translate into millions of dollars for low-income students, argues a controversial new report released Thursday. The report, from the nonprofit advocacy group the Education Trust, breaks down data on some of the largest endowments in the country, those with more than $500 million in assets. The Education Trust argues that many wealthy institutions have the capacity to put more endowment money toward low-income students with what would be a relatively small change in their spending habits -- and that they should.

“In our opinion, institutions are doing a lot for low-income students, but they’re not doing nearly enough,” said Andrew Nichols, director of higher education research and data analytics at Ed Trust. “They can do a lot more, given the benefits they are given regarding the endowment not being taxed.”

That argument is generating pushback from institutions and business officers, however. Many contend endowment spending has to be carefully managed to balance the high returns of boom years with the busts. Others point out that endowment funds are restricted for dozens of priorities and that donors can’t always be persuaded to give money without strings attached to their passions or pet projects.

The debate comes at a time when large endowments are already under the microscope. Congress scrutinized endowment spending this year, and U.S. Representative Tom Reed has also pitched the idea of restricting part of large endowments’ earnings for student aid.

Even with that recent history, the Education Trust is not making a firm policy recommendation for endowment spending, Nichols said. Instead, it is pushing the issue of using endowments to fund low-income students, and advocating for better data about endowments and how they are spent.

“It’s not a core fix, we understand that,” Nichols said. “But what we’re looking at is institutions that have a capacity to do a lot more, and we want to nudge them to do more for low-income kids.”

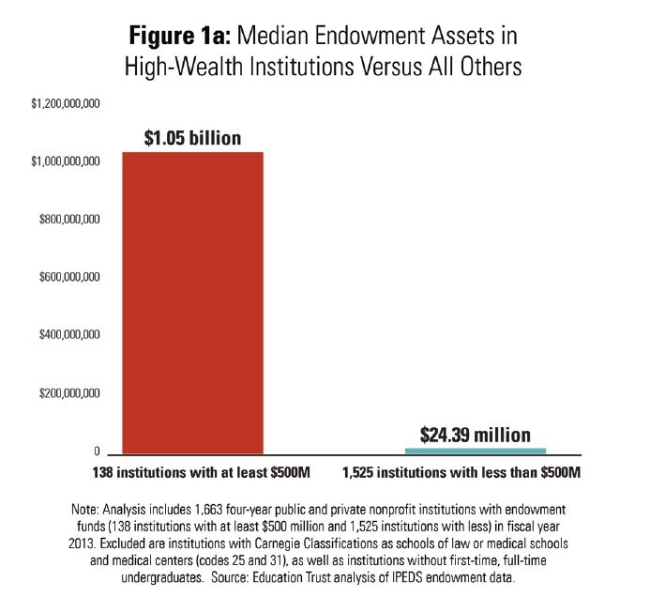

The Education Trust started by looking at 138 institutions that had more than $500 million in endowment assets in 2013. Those institutions accounted for about 3.6 percent of the country’s colleges and universities but represented 75 percent of higher education endowment wealth, the report said.

The group then collected data on endowment resources and spending at the institutions. Because of difficulties gathering data -- many institutions are made up of various entities with different tax identification numbers and names -- Education Trust ultimately limited its analysis to 67 private nonprofit institutions with endowments at or above the $500 million mark.

It found that new contributions added 3.1 percent annually to the institutions’ endowments, on average, between 2010 and 2013 -- after accounting for investment gains and spending. The endowments generated an average annual return on investment of 11.1 percent during the time frame.

Once all forms of spending, contributions and investment gains were taken into account, the report found that average endowment grew by 8.8 percent per year during the period. When the 2010 fiscal year started, the 67 institutions’ endowments were worth a total of $149.5 billion. In four years the number grew to $202.3 billion.

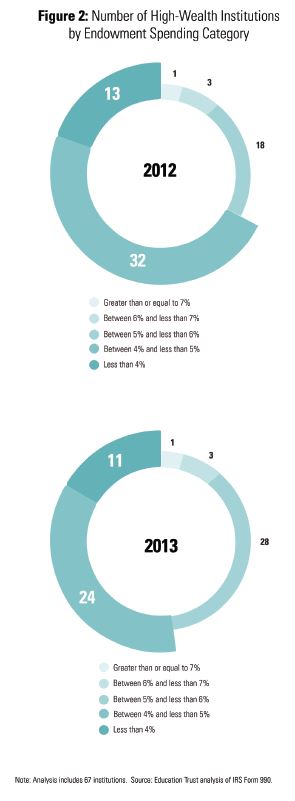

Collective spending at the universities tallied more than $9.3 billion in 2013. But the group’s median annual spending rate from endowments came in at 4.6 percent in the 2012 fiscal year and 4.9 percent in the 2013 fiscal year.

The median rate appears close to a 5 percent minimum spending benchmark required of private nonprofit foundations. University endowments aren’t covered by those minimum spending rules, but some critics of endowment spending levels have suggested the 5 percent level as a floor for what endowments should be required to spend. The Education Trust found 35 institutions' endowments did not meet that 5 percent spending benchmark in 2013.

The group ran calculations to find out what would happen if the 35 institutions boosted their endowment spending to 5 percent and put that extra money toward low-income students -- defined as those from families with incomes at or below $30,000. Such a move would make available $418 million, it found.

That would pay tuition for 2,376 low-income students, an increase of almost 67 percent in the number of first-time, full-time low-income students enrolled at the institutions as of 2012-13. Or it would allow the 35 institutions to cut their net price for low-income students by an average of $8,000 per year.

The report notes that the 67 institutions in its sample vary widely in their spending potential. Endowment spending at individual universities in 2013 ranged from as little as $11.5 million to $1.4 billion, with spending rates varying as well.

Consequently, boosting spending to 5 percent at applicable universities generates vastly different dollar amounts. Brown University, for instance, would make available $1.78 million if it boosted its spending rate to 5 percent, the Education Trust found. The University of Pennsylvania would make available $64.6 million.

An increase of $64.6 million would be enough to double Penn’s number of low-income students entering campus from 109 to 218, the report said. It would also cover costs for those 218 students for four years while leaving money left over, the report estimated.

Penn took issue with several parts of the report. Many of its endowment units are restricted, Vice President of Communications Stephen J. MacCarthy wrote in a response sent to the Education Trust. MacCarthy also said that data drawn from Penn’s forms filed with the Internal Revenue Service led to misleading conclusions, because the institution's university-owned hospital was included in its Form 990.

“Therefore, the calculation that Penn spends 4 percent is misleading, because it includes hospital-related endowments in the denominator which could not be used to support financial aid,” MacCarthy wrote. “If the hospital-related endowments and associated spending were excluded from your calculations, Penn’s effective rate would be 5.1 percent -- above the target you are advocating for in your report.”

Penn has established a two-tiered spending rate for its endowments. The rate for non-aid endowments was recently raised to 5 percent. The effective spending rate for Penn’s financial aid endowment was 6.5 percent in 2013, MacCarthy wrote.

He also argued that spending more from endowments today can come at the cost of endowment spending in the future. Steven Bloom, the director of government relations for the American Council on Education, made the same point, adding that colleges and universities need the freedom to balance their endowment spending to make sure money is available in the future.

“It allows the schools the flexibility to adapt their spending based on the value of their endowments over time,” Bloom said. “Based on the real world.”

Bloom said the timing of the study covers a period when endowment returns were high. But the situation is different today, with investment returns slipping to an average of 2.4 percent for the 2015 fiscal year, according to an annual survey by the National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund. A report this week said that endowments are on track to have their worst year since 2009. Funds with more than $500 million had a median loss of 0.73 percent in the just-ended fiscal year, the report said, citing Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service data.

Critics took aim at other parts of the Education Trust report as well.

“They ignore that access and affordability are only part of the equation that schools are dealing with when they’re trying to meet their public purpose,” said Liz Clark, director of federal affairs at NACUBO. “Many of these schools have complex missions that include research, health care, public service -- and endowment spending can go toward all of that.”

The Education Trust report suggested strategies to free more funds to aid low-income students. Institutions could make it a bigger priority to raise money for low-income students or set aside portions of all new gifts for that purpose, it said. They could also try to renegotiate existing endowment agreements with donors.

However, fund-raising is not simply a one-way conversation, said Ken Redd, NACUBO's director of research and policy analysis.

“Many schools already do those kinds of things before gift agreements are signed,” Redd said. “There are always those conversations back and forth about what a school’s needs are, but ultimately it’s the donor’s money. If a donor decides they want to support the engineering school or the hospital or research, then certainly a school has to honor that.”

Nichols maintained that endowments and donation agreements can be simplified.

“They are complicated,” Nichols said. “But that doesn’t mean they have to be complicated. Our suggestion is that the institutions aren’t passive actors in this fund-raising business. They often go after funds for specific purposes, and they end up being restricted. But if they want to start significant capital campaigns to raise money for low-income students, they could do that.”

He also said that more public data should be available on endowments and endowment spending. The funds are tax advantaged, he said.

“There’s no minimum spending rate, and there’s no taxes,” Nichols said. “Because they are subsidized by all taxpayers, we would expect for there to be some public information on endowments. We would also expect for these institutions that really have the capacity to do a great deal for low-income students to do as much as they can.”

Nichols also argued low-income students are relatively scarce on many campuses with the largest endowments, an issue that the organization has hammered home for years, focusing in particular on elite public flagship universities.

Almost half of institutions with endowments of $500 million or more were in the lowest 5 percent nationally for enrollment of Pell Grant recipients, a proxy for low-income-student enrollment, according to the Education Trust report. Nearly four of five of those institutions posted an annual net price that is more than 60 percent of a low-income student’s annual family income.

“What we’re saying is when we look at the data, what we see is there are still very few low-income students on these campuses,” Nichols said. “And they’re still paying a significant amount in terms of their net price.”