You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

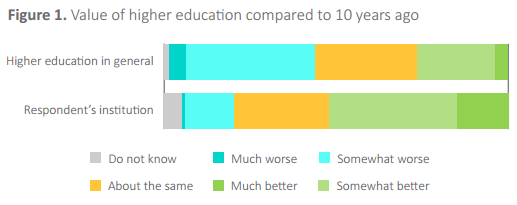

Academic leaders say all the other colleges and universities out there are responsible for why higher education is delivering less value than it did 10 years ago, an upcoming report found. Their own institutions, they say, are doing even better than before.

The report, based on a survey of 218 high-ranking administrators -- including presidents, vice presidents and provosts -- at private and public two- and four-year institutions, explores the barriers preventing colleges from improving student outcomes. The report, which will be published Sept. 29, suggests many colleges are struggling with a “bystander effect”: everyone is responsible for improving student outcomes, so no one takes ownership of it.

Eduventures, the Boston-based research and consulting firm behind the report, gave Inside Higher Ed an advance look at the findings. James Wiley, a principal analyst at the firm who wrote the report, said the survey responses suggest a “misalignment” between how college leaders view the work taking place at their own institutions compared to higher education more broadly.

“The overarching takeaway is that it’s very unclear what ‘student outcomes’ means,” Wiley said in an interview. Without a clear sense of which metrics they should be looking at to determine how students are performing, colleges are creating uncertainty around what technology could benefit students and who should be responsible for managing that work, he said.

The report identifies five obstacles hindering colleges from improving student outcomes, ranging from a lack of focus on teaching quality to organizational barriers. But the attitudes expressed by college leaders also raise questions about whether they feel the push to improve higher education should start on their own campuses.

About half of respondents said the value offered by their own institutions is much or somewhat higher than a decade ago. Another quarter said it is roughly the same. Asked to rate higher education as a whole, about three-quarters of respondents said the value has decreased or remained the same.

The split in some ways resembles the difference between the disapproval voters feel about Congress versus the high marks they give their own representative, Wiley said.

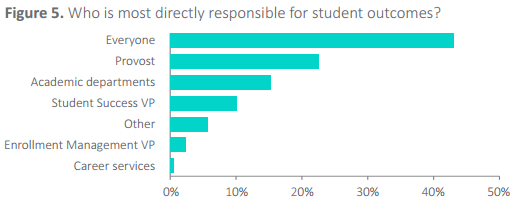

The same finger-pointing emerges when looking at who college leaders say should be most directly responsible for student outcomes. The No. 1 answer, selected by more than 40 percent of respondents: everyone. Less than a quarter of respondents each picked a more specific answer, such as a provost or a vice president of student success.

Wiley said he was surprised that nearly half of the senior academic leaders surveyed couldn’t point to a single individual or office in charge of improving student outcomes. “If you don’t own it, then who does?” he said.

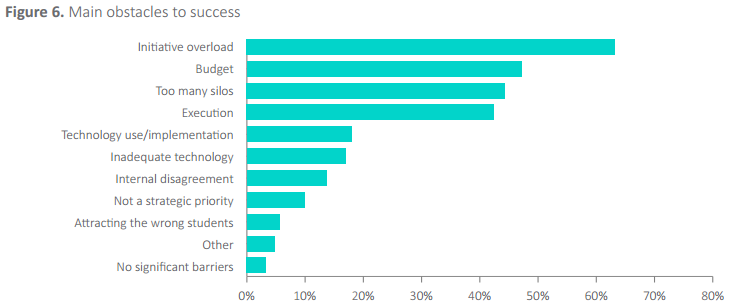

The lack of clearly defined leadership roles may stem from the fact that many academic leaders feel their institutions are stretched too thin. The top organizational barrier preventing colleges from improving student outcomes, according to 63 percent of respondents, is initiative fatigue -- that they simply have too many pilots and projects going on to focus. Budget constraints placed second on the list, with slightly less than half of respondents naming it their top barrier.

“What I’m sensing is a bit of a vacuum,” Wiley said. “Leaders are pulled in all directions, and if there’s no real ownership or space to do anything, then what fills that void?”

Gunnar Counselman, CEO of the ed-tech company Fidelis, who worked with Eduventures on the report, said he often hears about initiative fatigue from his customers. The company supplies learning relationship management software to colleges.

“Higher education is drowning in initiatives right now,” Counselman said in an interview. “What’s happened in the last 10-12 years is that higher ed has recognized that what got them here is not going to get them there. They’ve recognized that they’re going to have to change, and as a result of that … they’ve put a dozen initiatives in the water.”

College leaders are also uncertain about what kind of technology they need to invest in to improve student outcomes, the survey found. A majority of respondents (56 percent) said their top priority for investing in technology is to boost admissions and enrollment, compared to about one-third (37 percent) who picked improving student outcomes.