You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Haverford President Kim Benston and former President John Coleman at alumni weekend in 2016

Haverford College

A story has been circulating among Haverford College alumni about former President John Coleman placing a washing machine on Founder’s Green, at the heart of campus.

The Vietnam War was raging, and student protests roiled campuses across the country. Haverford was home to its own protests, including by those who wanted to burn an American flag. But Coleman convinced protestors to wash it instead, avoiding image of a flag burning that so many find offensive, but still allowing the protest to continue.

Coleman’s grandson, William Coleman, only heard that story this month, after his grandfather died Sept. 6 at the age of 95. But to him, it says a lot about a man who has been noted as exceptional for his principled stands on social issues and opposition to the Vietnam War.

Coleman’s grandson, William Coleman, only heard that story this month, after his grandfather died Sept. 6 at the age of 95. But to him, it says a lot about a man who has been noted as exceptional for his principled stands on social issues and opposition to the Vietnam War.

“There are a lot of rosy pictures when we’re in eulogy mode,” said William Coleman, an art historian who is a postdoctoral fellow at the Library Company of Philadelphia. “But I think he did navigate a difficult time quite well.”

The Haverford president’s Vietnam activism also included recruiting dozens of other college and university presidents to sign an antiwar statement and organizing buses to take hundreds of students, faculty, staff and alumni to a Washington, D.C., protest. The president, known as Jack, was widely regarded as accessible, often eating with students.

Obituaries have noted many other ways Jack Coleman stood out from the crowd of college and university presidents while he headed Haverford, a small liberal arts college with Quaker roots outside Philadelphia, from 1967 to 1977. His record on athletic decisions included some controversy. He decided to kill the college’s football program. He eliminated a rule preventing long-haired and bearded students from competing on intercollegiate teams.

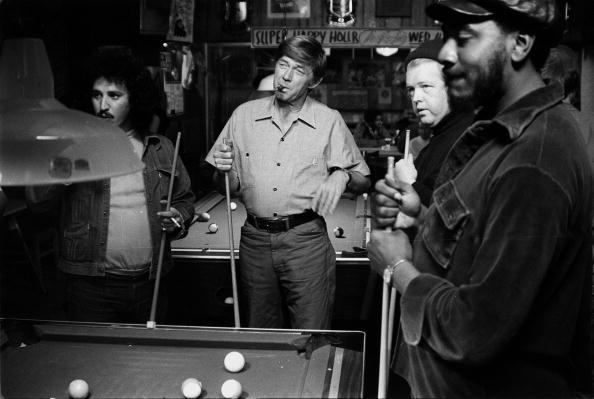

He is perhaps best known for taking a series of blue-collar jobs while on sabbatical in order to explore the gap between academics and workers -- hauling trash in a Maryland town, making sandwiches in a Boston restaurant and digging sewer lines in Atlanta. The undercover work eventually fed the widely known book Blue Collar Journal: A College President’s Sabbatical, and, later, a TV movie, The Secret Life of John Chapman. (The photograph at right, from Getty Images, shows the actor Ralph Waite, portraying Coleman, playing pool with friends he made at one of his blue-collar jobs.)

He is perhaps best known for taking a series of blue-collar jobs while on sabbatical in order to explore the gap between academics and workers -- hauling trash in a Maryland town, making sandwiches in a Boston restaurant and digging sewer lines in Atlanta. The undercover work eventually fed the widely known book Blue Collar Journal: A College President’s Sabbatical, and, later, a TV movie, The Secret Life of John Chapman. (The photograph at right, from Getty Images, shows the actor Ralph Waite, portraying Coleman, playing pool with friends he made at one of his blue-collar jobs.)

The president also became a proponent of admitting women to then all-male Haverford, a politically difficult stance given the college’s relationship with the nearby women’s college Bryn Mawr. Haverford’s Board of Managers rejected a plan to directly admit first-year women, instead deciding to admit women as upper-class transfer students. The decision led to Coleman resigning after 10 years as president. Haverford would go on to begin admitting women three years later, in 1980.

Many parallels exist between the times of Coleman’s presidency and today, when student protests are again breaking out on campuses and many college and university leaders are taking criticism from being too far removed from society at large. There are key differences, too, both in circumstances and leaders. It can be hard to imagine today’s image-conscious college presidents slipping unnoticed into a restaurant’s kitchen -- or organizing buses for a protest in Washington.

It is, however, important to recognize the context of the day in which Coleman was a president, as well as the way things have changed. Several other presidents came out to criticize the Vietnam War, such as John William Ward of Amherst and Kingman Brewster of Yale, said John Thelin, a professor of history of higher education and public policy at the University of Kentucky College of Education.

“They were trying to have presidents step outside of their offices a little into a variety of social issues that were pretty potent in the ’70s,” Thelin said. “They included not only war, but, I think, some consciousness and sensitivity about the plight of labor and working-class Americans.”

Still, it was a relatively small group -- and it didn’t set off widespread trends in college and university presidencies. If anything, presidents today face more criticism for having a lack of vision and being farther removed from society at large.

“I’m not overwhelmed by college and university presidents in terms of their courage and clear thinking,” Thelin said. “But by and large, I don’t think college and university presidents, whether in the 1970s or today, have been genuine leaders.”

The role of president remains an isolating job, said Susan Resneck Pierce, president of SRP Consulting and former president of the University of Puget Sound. Presidents today can still do many of the things for which Coleman is lauded, like being highly involved with students or speaking thoughtfully on important issues, she said.

Other circumstances have changed. Today’s media climate makes it more dangerous than ever to take a public stance on a contentious issue, according to Pierce. Social media lets partisans attack immediately. Websites allow opponents to organize or leak damaging documents.

The realities of today’s media also make it harder for a president to escape campus.

“In the past, the president might well have gone to a community a reasonable distance from campus and been anonymous,” Pierce said. “I don’t think that’s possible now.”

University of California, Riverside, Chancellor Timothy White in 2011 disguised himself for a week of doing jobs across campus for the CBS television show Undercover Boss. But White, who is now California State University chancellor, was on his own campus with television cameras in tow.

That’s not exactly the same thing as Coleman’s blue-collar sabbatical.

“I wanted to get away from the world of words and politics and parties -- the things a college president does,” Coleman told The New York Times in 1973 of his undercover work. “As a college president, you begin to take yourself very seriously and think you have power you don’t. You forget elementary things about people. I wanted to relearn things I’d forgotten.”

Coleman continued his undercover work after he left Haverford. He became the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation president, focusing in part on prison reform. He spent time as an inmate or guard in several prisons, writing publicly about his experience.

He continued to follow the college and university world, according to his grandson. The former president, who held a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago, was inspired to see racial justice gaining attention on campuses. He was also worried about the trend away from scholar-administrators.

“He was concerned about a trend of the M.B.A. college president, thinking there is still a place for somebody who comes up through the professorial ranks and understands the value of the faculty,” said William Coleman.

William Coleman tells another story about his grandfather, one illustrating that, even in the 1970s, college presidents felt the pull of different constituencies. Haverford had not required caps and gowns for graduation in the early ’70s, but Jack Coleman ultimately decided to require regalia again, William Coleman said. He later told his grandson that allowing students to graduate without regalia was his greatest regret.

“This was a man who really enjoyed being with the people and was not, I think, a defender of pomp and circumstance,” William Coleman said. “He came to believe he had let down the parents, that the ceremony was for the parents who had worked so hard to send their children to Haverford.”

Jack Coleman himself said an institution’s president was at the center of conflicting interest groups, according to his obituary published by Haverford.

"In actuality, a president is at the center of a web of conflicting interest groups, none of which can ever be fully satisfied," the obituary quoted him as writing. "He is, by definition, almost always wrong … It’s all very interesting, and not hard to take once he gets over wanting to be right and settles instead for doing the best he can."

Commenters on social media seemed drawn to that type of insight. One, Peter Leibold, recounted the story of the washing machine heading off a flag burning. He said he did not know if it was fictional or true but that he had applied to Haverford because of such stories.

“I always thought that was so insightful and so Haverfordian in its approach,” Leibold wrote.

Coleman was the first non-Quaker president at Haverford when he took over, but he became a Quaker before resigning.