You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

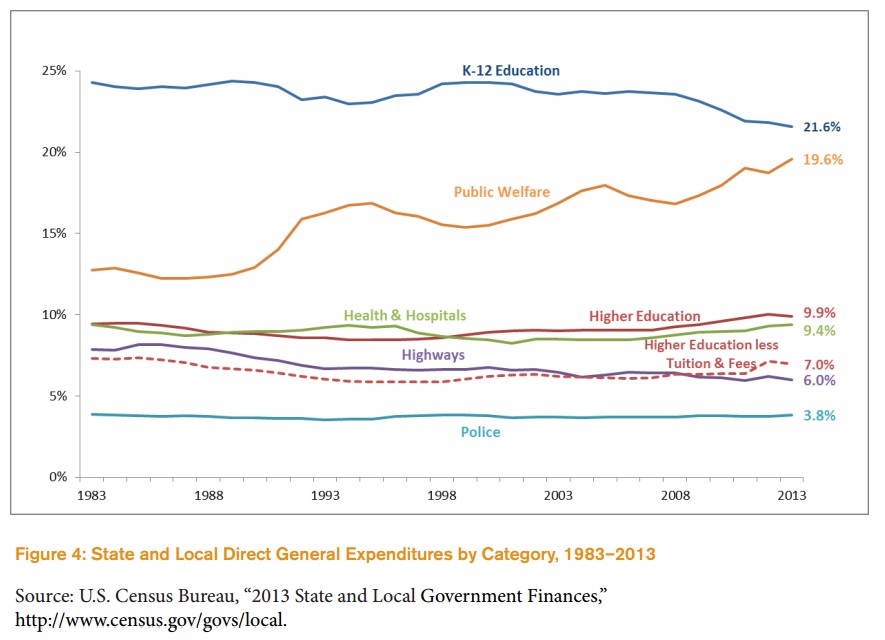

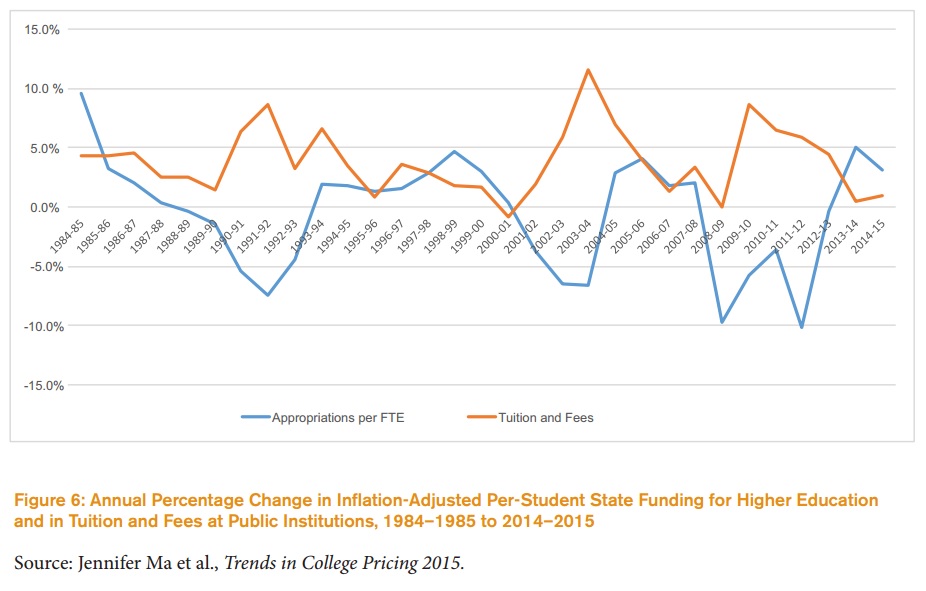

During the last 25 years, states have been paying an ever-shrinking portion of the costs of educating students at public colleges. That trend will be hard to reverse, as spending on Medicaid and other competing needs is likely to increase in most states.

To cope with the bleak budget outlook, two new papers by prominent higher education researchers seek to make states’ higher education dollars go farther and to improve degree completion rates with a set of proposals that some in higher education may find controversial.

For example, one paper suggests reallocating state dollars to public colleges that enroll more low-income students, away from those with wealthier students. The other criticizes free-college proposals, saying they will hurt lower-income households most, and calls instead for prioritizing the use of tuition revenue on need-based financial aid.

The University of Virginia’s Miller Center on Tuesday released the reports, which are two of six new papers prepared for the National Commission on Financing 21st Century Higher Education. The Miller Center created the nonpartisan commission in 2014 with funding from Lumina Foundation.

Bridget Terry Long, a professor of education and economics at Harvard University, wrote the paper on redistribution of state support. In 2015 states spent $81.8 billion on higher education, she wrote, with an additional $9.1 billion in local government spending on community colleges.

While this amount dwarfs the $30.3 billion the federal government spent on Pell Grants last year, the report said all but four states have reduced spending per student since the recession.

State support for public higher education tends to skew toward more selective universities, Long said, with flagships receiving more per student than do other four-year institutions, which in turn get more than community colleges. And students from low-income backgrounds are more likely to attend less-selective four-year institutions or community colleges.

Some of the variation in state spending is due to the differing missions and focuses of colleges, according to Long. For example, research universities with strong STEM programs have different cost structures and also serve states’ needs beyond degree completion. Yet state subsidies generally favor higher-income, white students, who tend to be better prepared academically for college.

“If the goal is to improve rates of student persistence and degree completion, there is a need to devote more resources to the institutions that have students who are less prepared,” Long writes, “because state aid does little to address inequities in funding; in fact, it may exacerbate them.”

Community colleges in particular struggle amid declining state support, in part because they face more pressure to hold down tuition prices.

“Given the large numbers of students that community colleges serve, including many teetering on the edge of success or failure depending on the resources and support available to them,” said Long, “it is imperative that states devote more funding to these institutions and their students if serious progress is going to be made toward improving educational attainment in the United States.”

More funding for community colleges and less-selective four-year institutions is needed to help them get more students to graduation, according to Long. And she said supporting student success is often overlooked by state governments as they determine how to allocate money for higher education, including through performance-funding formulas.

“Policies should be careful not to award institutions that cater to students who already have a high likelihood of success,” Long wrote. “Instead, funding should be geared toward institutional efforts to help at-risk students make progress toward their degrees.”

However, Long cautions against a zero-sum approach to redistribution at the state level, in part because all types of public colleges are struggling with state disinvestment.

“It is unlikely that we will make much progress toward the goal of increasing educational attainment by robbing Peter to pay Paul,” she wrote “Instead, institutions will need additional resources to really improve student outcomes.”

Pushing Back on Free

Long’s paper calls for states to spend more on targeted, need-based aid. So does the paper by Sandy Baum and Kim Reuben of the Urban Institute.

Baum is a senior fellow at the institute and professor emerita of economics at Skidmore College. She also previously advised Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. In the paper, she and Reuben, a senior fellow at the institute, describe public college tuition as “user fees,” a term that applies to highway tolls, trash collection and other government services that are not pure public goods.

“User fees allocate the costs of the public service according to individual consumption levels,” they write. “These fees frequently pay only a portion of the total cost of the service, with tax revenues covering the remainder.”

The challenge in this view of public higher education, according to Baum and Reuben, is determining what the appropriate breakdown between taxpayer support and student tuition should be.

But because students who earn college degrees are more likely to end up in higher-income brackets, they write that there is a strong argument for “maintaining student contributions to pay for college education as long as mechanisms such as need-based financial aid ensure that low-income students are not excluded and that provisions for loan repayment include income-driven options, protecting borrowers whose higher education does not pay off well financially.”

The paper’s central theme is that states should fund higher education with a combination of user fees and general tax revenues, with the tax burden falling most heavily on wealthier people.

As a result, Baum and Reuben said free college proposals are illusory and would be harmful to the less wealthy. Clinton's campaign, while stopping short of the tuition-free plan Bernie Sanders proposed, has called for debt-free public college.

“There is no such thing as free college,” Baum and Reuben wrote. “It is important to understand that lower tuition means higher taxes and increases the burden on all taxpayers, including and often primarily lower-income households.”