You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

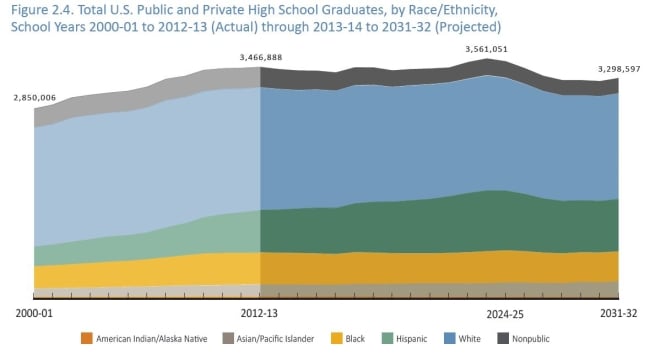

A new report projects the population of Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander high school graduates will grow, even as overall graduate levels stagnate and eventually drop.

WICHE

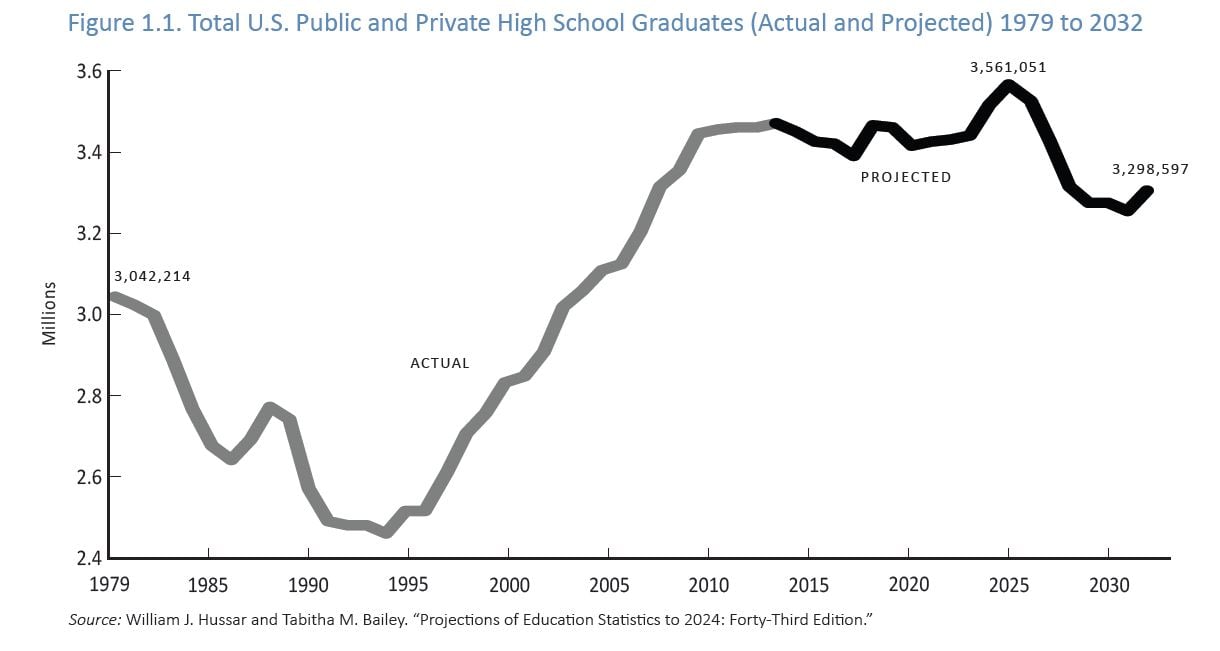

A decade-long stagnation in the number of U.S. high school graduates is setting in, and the number of students receiving diplomas in 2017 is expected to drop significantly.

The stagnating number of graduates breaks nearly two decades of reliable increases and comes as significant demographic changes reshape where students live and from what backgrounds they come. The pool of high school graduates is projected to become less white, more Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander, and increasingly located in the South over the coming years, according to a new set of projections in a report released Tuesday by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education.

WICHE’s projections, typically released every four to five years, are closely watched as a window into enrollment trends across the United States. The trends carry significant implications for policy makers trying to align educational priorities with job markets -- and with colleges and universities attempting to plan their classes of the future. The new projections mean higher education systems will have to change, according to Joe Garcia, a former lieutenant governor of Colorado and former campus president who is president of WICHE.

“We’re simply going to have fewer students in our K-12 system, and we’ll be producing fewer graduates,” Garcia said during a conference call to discuss the report’s findings. “That has significant implications to our institutions -- our colleges and universities -- as well as to our employers and our work force.”

The decade of stagnation is projected to run from 2013, when enrollment hit 3.47 million, through 2023. During that time, the annual number of high school graduates in the country is expected to slot in between 3.4 million and 3.5 million. However, a substantial drop is expected in 2017. The number of high school graduates is projected to fall by about 81,000, or 2.3 percent, that year.

It looks like a big decline. However, it’s not so huge that colleges and universities will need to brace for large disruptions, as long as they reach out to more students, Garcia said.

“They will need to brace if they’re not embracing the new student population,” he said, referring to the expected increases in Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander graduates. “They do need to be going after those populations that are increasing.”

Further into the future, enrollments are projected to grow from 2024 to 2026. A new peak enrollment of 3.56 million is projected in 2026. It will be driven by an increase in the number of nonwhite graduates.

Afterward, however, enrollments are projected to drop off significantly. From 2027 and 2032, the average graduating class size is expected to fall below 2013 levels.

The plateauing and eventual projected decline of high school graduates brings to an end 15 years of consistent increases. The population of high school graduates jumped from 2.52 million in 1996 to 3.47 million in 2013, which is the last year confirmed graduation tallies are available.

It's worth noting that the latest available data show higher high school graduation levels from 2009-2012 than were predicted in WICHE’s last round of projections. The commission said stronger growth and retention of high school students and slightly greater 12th-grade graduation rates contributed to the difference. WICHE research suggested that the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals immigration policy, put in place in 2012, may have contributed to increases in the overall number of high school graduates.

Commission officials declined to speculate on how new immigration policies under President-elect Donald Trump could affect their future projections.

Demographic Changes

Previous WICHE projections have warned of peaking numbers of high school graduates and projected increasing diversity among graduates. But experts said Tuesday’s projections represent a new challenge to the status quo at institutions, one that pointed toward increased efforts in recruiting minority students and poor students -- and keeping them on campus.

Tuesday’s report projects Hispanic graduates spiking by 50 percent at public high schools from 2014 to the mid-2020s. That would mean about 920,000 graduates per year around 2025. Asian/Pacific Islander graduates from public high schools are projected to spike by 30 percent over the same time frame. The total number of black public high school graduates is expected to level off and decline slightly after peaking at about 480,000 from 2010 through 2012. Projections have the number of black high school graduates slipping by about 6 percent between now and the early 2030s.

In sharp contrast, the number of white public high school graduates is projected to fall by 14 percent between 2013 and 2030. The population of white public high school graduates is projected to decline by about a quarter of a million people between 2013 and 2032, to 1.6 million.

Initially, growth in nonwhite public school graduates will be enough to essentially balance out consistent declines in the white graduate population -- that’s how current graduate levels can plateau even as numbers of white graduates plunge. The balancing out runs to 2023 before a spike in nonwhite graduates drives up overall graduate levels. From 2024 to 2028, nonwhite graduates are projected to increase by 150 for every 100 white high school graduates dropping off the charts. But then from 2029 to 2032, nonwhite high school graduates are projected to dip back below 1.5 million, roughly the same as 2020 levels. That’s still 12 percent higher than 2013.

Experts said the projections indicate that higher education institutions will need to increase pathways to college for minority students while also making an effort to help those students stay on campus and graduate with degrees. That’s true for institutions recruiting Hispanic students, according to Deborah A. Santiago, co-founder, chief operating officer and vice president for policy at Excelencia in Education, a Washington-based nonprofit group focusing on Latino student success.

“Some could see this demographic and geographic shift as a threat to their status quo,” she said in an email. “It is. We should collectively acknowledge traditional efforts to serve traditional students have not sufficiently closed achievement gaps in high school or in college attainment for posttraditional students (those who do not fit the majority profile). If they had been effective, we wouldn’t currently have gaps in achievement and attainment. Identifying new ways and new categories of students to recruit is a clear opportunity to be proactive in positioning to serve a wider profile of posttraditional students.”

Colleges and universities will need to recruit and keep students who traditionally have not completed college at high rates, according to William Serrata, president of El Paso Community College, in Texas.

“It’s imperative upon our institutions of higher ed to increase the college-going rates of all students, but in particular the students who are low income, first generation and students of color,” Serrata said during the conference call on the projections. “This is really a road map for us in higher education to really change our strategies to focus on increasing college-going rates amongst those populations and then facilitate their success once we have them.”

Regional Variations

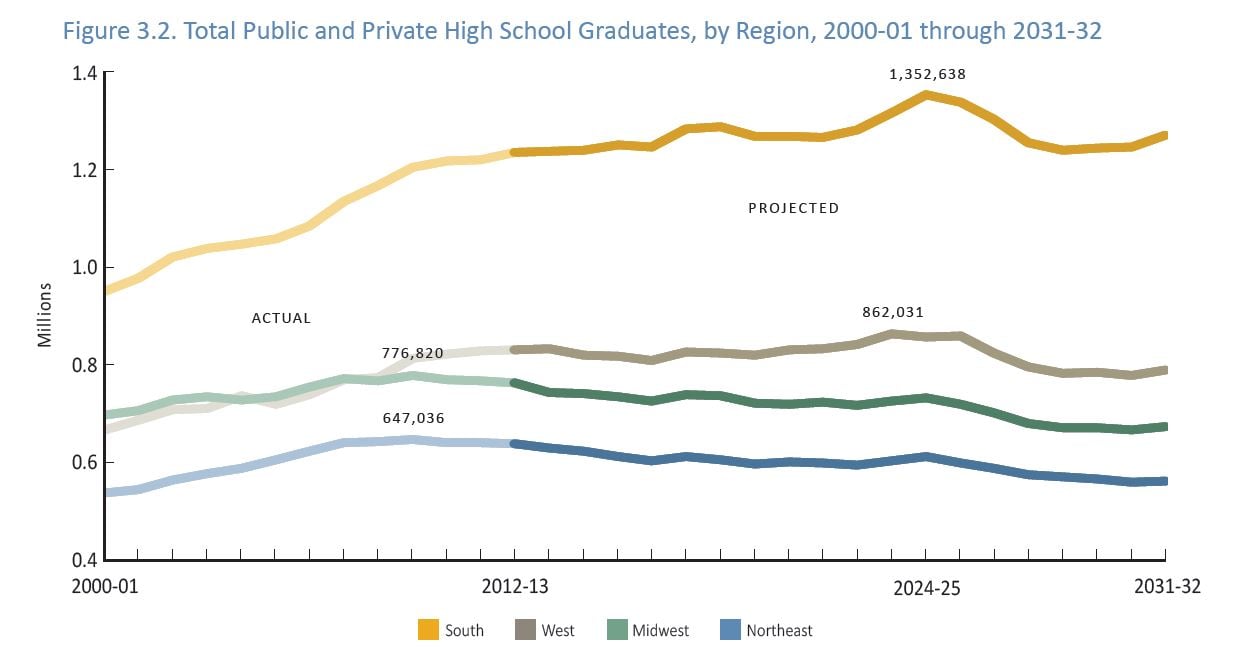

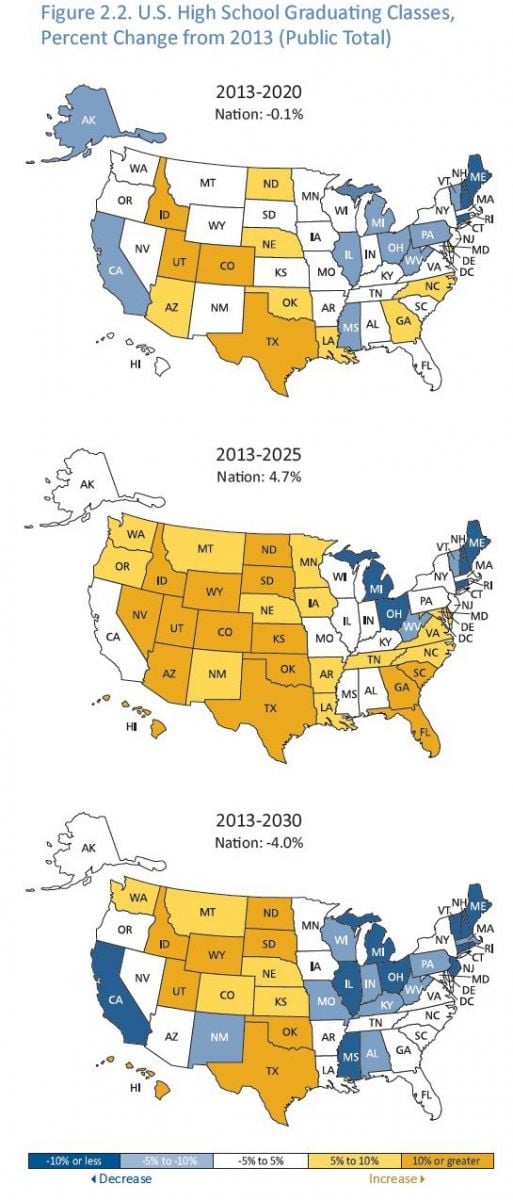

Changes in graduating class sizes are expected to vary significantly by region and state. The Northeast and the Midwest are projected to experience declining numbers of graduates. The West will be home to slight increases. The South will see steady, significant increases.

The rise of the South is a continuation of recent trends. About a third of the country’s high school graduates were located in the region in the early 2000s. That portion had grown to about 43 percent -- or 1.23 million graduates -- by 2013. It’s expected to jump to nearly 47 percent of graduates, 1.35 million people, by about 2025. After that peak, projections show the South continuing to produce roughly 45 percent of the country’s high school graduates, even as overall graduate numbers decline after 2025.

Meanwhile, the Western United States is projected to see some growth, keeping a relatively steady share of the country’s graduates. The population of graduates in the region is expected to grow from 813,400 in 2010 to 860,000 in 2024 before settling back at 784,000 by the early 2030s. The West’s graduate levels as a portion of the country’s total should come in between about 25 and 30 percent throughout that period.

The Midwest is projected to drop from 22 percent of the country’s high school graduates in 2013 -- about 762,000 people -- to 19 percent by 2030. Annual graduates will drop by approximately 93,000 in the region. The Northeast is projected to drop from 18 percent of graduates in 2013 -- 639,000 graduates -- to 16 percent (567,000) by the early 2030s.

Public high school graduates drive the projected trends, as they represent 91 percent of the country’s high school graduates. Still, it is worth noting that WICHE projects private high schools to lose far more graduates than their public counterparts. Private high schools are projected to lose about a quarter of their graduates over 20 years. That would drop them from 302,000 in 2011 to 220,000 by the early 2030s. Private school enrollment declines are fueled by drops in religious schools of all affiliations, particularly Catholic high schools.

Even within regions, states are expected to experience significant differences in changes to graduation levels. For example, in the Northeast, Connecticut is projected to see a 26 percent drop, from 44,495 high school graduates in 2011-12 to 32,968 in 2031-32. Neighboring New York, in contrast, is projected to lose a smaller portion of its annual graduates, dropping 6 percent from 212,474 to 200,020 in the same time frame.

Policy Implications

Taken together, the changes mean colleges and universities are likely to feel increased enrollment pressures. The WICHE report notes that institutional leaders will not be able to count on “a steadily increasing stream of high school graduates knocking at their door.”

Policy makers might take note. Enrollment pressures can lead to work force pressures, said Nicole Smith, a research professor and chief economist at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

“Once we have a declining set of students from high school, we would expect, in a true pipeline fashion, to have a commensurate decline in entrance into college, and then those who are available for the work force,” she said during the conference call.

The demographic changes indicate colleges and universities could have trouble filling their classrooms with enough academically prepared students who can pay full tuition, said Garcia, WICHE’s president. That could mean financial stress as budget cuts sweep many states.

“University presidents are in a tough spot, because they’re squeezed as states start spending less money on their public institutions,” said Garcia. “Frankly, tuition matters. What those presidents may understand is it’s their obligation to serve all students, but the financial challenge is if they don’t recruit more well-prepared, well-resourced, full-pay students.”

Still, there is opportunity in bringing new student populations onto campuses, said Demarée Michelau, vice president of the office of policy analysis and research at WICHE.

“I caution us to not just think of the challenges that are ahead of us, but to think of this as an opportunity,” she said during the call. “A lot of the changes that come with serving diverse populations help all students. They’ll help adult students. They’ll help traditional students.”