You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

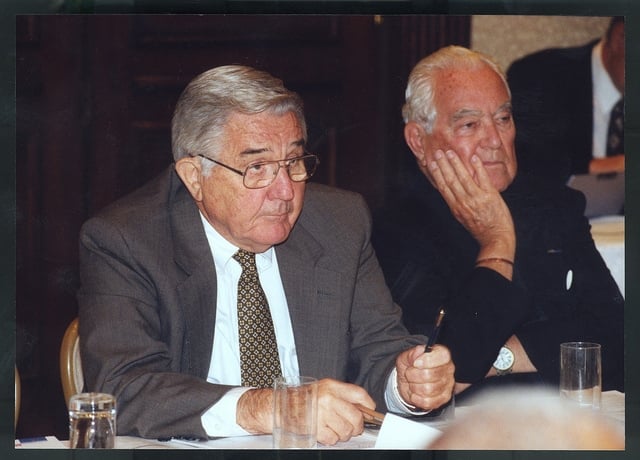

William C. Friday and the Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh at an early meeting of the Knight Commission

Knight Commission

Twenty-five years ago, the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics released its initial report, called Keeping Faith With the Student-Athlete. Widely considered groundbreaking at the time, the report urged the National Collegiate Athletic Association and college leaders to overhaul how college sports were run. Presidents, not athletic directors, should be in charge, the commission argued, and they should focus on three goals: academic integrity, financial integrity and independent certification.

Founded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation in 1989, the group brought together some influential leaders in higher education and college sports. Members in those early years included the highly esteemed presidents of the Universities of North Carolina and Notre Dame, William C. Friday and the Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, who led the panel; the then presidents of Southern Methodist University and Michigan State Universities, A. Kenneth Pye and John A. DiBiaggio; and future Secretaries of Education and Health and Human Services Lamar Alexander and Donna E. Shalala. Four years after that first report, the NCAA restructured, handing the association’s governance over to college presidents, just as the commission had recommended.

In October, signs of the commission’s influence surfaced anew when the NCAA agreed to alter its formula for distributing television revenues to members to account for the academic performance of their athletes -- an approach the Knight panel had advocated. A changing of the guard at the commission, prompted by the recent retirement of its longtime co-chairman, William (Brit) Kirwan, offers a logical time to assess its impact on the college sports landscape.

While the panel has had successes, many observers agree that its overall influence has been limited, largely overwhelmed by the growing commercialization of the college sports complex and the forces arrayed in support of it.

“The notion that the Knight Commission will lead the reform is probably no longer viable, since the real powerful drivers of change are likely to come from the financial side, related to the continuing growth of football revenue at the top end of the spectrum,” said John V. Lombardi, former president of the University of Florida and the Louisiana State University system. “The Knight Commission is mostly just one of many voices crying for reform. Money will be much more important in determining what happens to college sports than the principled voices of the endless crowd of critics.”

Reading the rhetoric surrounding the creation of the Knight panel in 1989 offers an overpowering sense of déjà vu.

At a news conference announcing the commission's creation, Hesburgh described the “crisis” that was facing big-time college athletics surrounding financial greed and the routine firing of coaches who develop young people but don’t win enough to satisfy boosters. “Worst of all, and this is the ultimate in hypocrisy,” he said, “is promising young people an education and then not giving them one …. The educational integrity that is squandered in this process is one of the greatest sins in higher education today.”

Friday and Hesburgh noted at that opening event that a similar commission established by the Carnegie Foundation in 1929 had identified a similar state of affairs. “If we can persuade people that there are serious problems, then we can do something,” said Father Hesburgh. “If we can’t, you can write [the commission] off like all of the others before us.”

The panel’s early work -- and the NCAA’s 1995 decision in response to it -- offered some hope that it might have more influence than those before it, said Allen Sack, a long-time professor of sports management at the University of New Haven who has studied and argued for reforming college sports for decades. About three-quarters of the recommendations in that first report came to pass, in some form or another, the commission stated in a second report in 2001. At the same time, that report noted, “the problems of big-time college sports have grown rather than diminished” in the intervening years.

Sack considered the Knight panel’s first report “revolutionary,” but the second one showed just how limited its influence might be, he recalls.

“I thought, ‘All of that money, all those trips, all those luncheons in all those big places in Washington, D.C., to bring people to these conferences, just to say things have gotten worse,’” he said. “That’s really something.”

The 2001 report, however, also included two more major recommendations that were (eventually) adopted in broad terms. In that report, the commission argued that the NCAA should bar from postseason competition any teams whose graduation rate is 50 percent or less. Three years later, the NCAA created a metric for measuring how many athletes are on track to graduate, called the academic progress rate. An APR of 1,000 means that a team is graduating -- or is on track to graduate -- all of its players. An APR of 930 means a team is graduating about half of its athletes.

In 2011, a decade after the commission first suggested the rule and a year after it reiterated the recommendation in a third report, the NCAA voted to adopt a new rule that restricted postseason participation to teams whose APR was 930 or higher.

In its 2001 and 2010 reports, the Knight Commission also recommended that the NCAA distribute some of its revenue to institutions based on academic performance. In October, the NCAA announced that it will do just that. Beginning in 2019, it will distribute millions of dollars in revenue to member institutions based on the academic performance of their athletes. The money will come from the association’s new $1.1 billion multimedia rights deal for the NCAA’s men’s basketball tournament. Colleges will be awarded the funds by earning “academic units” based on the academic performance of their teams, similar to how programs earn units based on how far they advance in the tournament.

The change came 15 years after the commission first suggested it.

Knight Commission members have expressed frustration about the slow pace of change. In a recent essay, Kirwan and former Education Secretary Arne Duncan, who joined the commission last year and is now its co-chairman (with Carol Cartwright, former president of Kent State and Bowling Green State Universities), urged Division I leaders to “move with a greater sense of urgency.” In an interview with Inside Higher Ed, Amy Perko, the commission’s executive director, said, “Clearly the commission would have liked to have seen quicker action on some” of its recommendations.

Still, Perko said, she believes the commission “feels like things are moving in a good direction.”

“We’re certainly encouraged by the influence the commission’s been able to have,” she said. “Within the past five years, the commission has directly influenced changes that better align college sports with educational values. It’s rewarding to see that there has been some action on a couple of those priorities.”

While its members are influential, the Knight Commission as an organization has no power over how college sports are governed. Furthermore, the commission is almost entirely focused on Division I college athletics, specifically the big-money sports of men’s basketball and football -- a space that is dominated by highly paid coaches participating in high-stakes competition, who have little incentive to listen to a group of academics and former athletes who are concerned with “de-escalating the athletics arms race.”

Writing for the journal On Sport and Society in 2001, Richard Crepeau, a sports historian who was at the time a professor at the University of Central Florida, wrote that the Knight Commission was “no match for the powers that be, which include boosters, alumni, television, sponsors, elected officials, trustees, students, some faculty and many university administrators” who are rewarded by big-time sports’ “highly commercialized nature.”

Cartwright, the commission’s other new co-chair (pictured above with Kirwan), said she is intensely aware of how difficult it sometimes is for the committee to actually be heard.

“Change is very difficult, and we don’t have the authority to just make something happen,” she said. “We have to lead through persuasion and we have to be as creative as can be. And we see it paying off, though it takes more time than we’d like it to take. Even as we take some pride in the impact we have had, there’s work to be done.”

David Ridpath, a professor of sports administration at Ohio University and president of the Drake Group, an organization pushing for more emphasis on academics in college sports, said he believes the Knight Commission has had a “profound impact” on intercollegiate athletics. Calling the group’s first report “seminal stuff,” Ridpath said that for a committee that can only serve in an advisory role, it’s impressive that NCAA has listened to the commission as much as it has.

How colleges and the NCAA have implemented some of those changes, however, has been “a mixed bag,” he said.

“The devil is in the details,” said Ridpath, who has long been an outspoken critic of the NCAA’s academic metrics. “Academic integrity sounds great on paper, but the NCAA’s metric leaves the system open for manipulation, as colleges are chasing a number and not focused on measuring actual learning. Putting college presidents in control of college sports seemed like a good idea, but some would say college presidents have ruined college sports. They’re in charge but don’t seem to be in control.”

At Kirwan’s final meeting as the Knight Commission’s chair Oct. 24, he expressed concern about “out of control” spending among the NCAA’s top conferences.

The expenditures, Kirwan said, are creating a financial divide that is making the Football Bowl Subdivision unstable and could eventually force out all but the wealthiest institutions. During the meeting, the Power Five leagues -- the 65 wealthiest programs, which gained the ability to create their own rules in 2014 -- received most of the blame for driving the increase in spending. In 2005, revenue generated by the Power Five leagues was $570 million. According to the Knight Commission, that revenue will be $2.8 billion by 2020.

Perko and Cartwright both said that the commission shares his concern, and that spending among Division I programs will remain a priority when the new leadership takes over next year. Indeed, the so-called athletics arms race has been among the commission’s chief concerns for decades. “A frantic, money-oriented modus operandi that defies responsibility dominates the structure of big-time football and basketball,” the commission wrote in its 2001 report.

Sack, of New Haven, said the amount of money involved in college sports may also be the primary reason the commission has not accomplished more of its goals. Sack recalled running into Friday, the original co-chair, at a conference shortly before his death in 2012. Sack said he asked Friday why the commission hadn’t made more progress.

“I’ll tell you the truth,” Sack said Friday replied. “It’s the money. There’s just too much, and we can’t do anything about it.”