You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

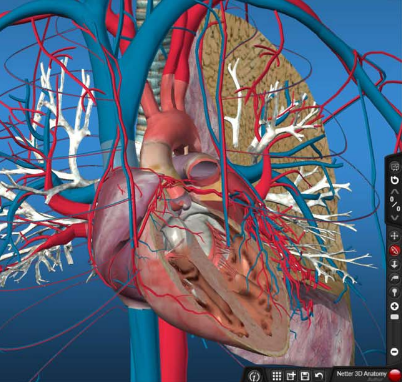

CyberAnatomy

Cutting into a digital cadaver can be more educational than the real thing for certain medical students, a new study found.

The study, “Use of Computer-Aided Holographic Models Improves Performance in a Cadaver Dissection-Based Course in Gross Anatomy,” compared the ability of 265 first-year med students to identify anatomical structures when looking at cadavers, preserved body parts and digital models. It found that especially students who are struggling in med school appear to benefit from being taught anatomy in several different ways.

Across three practical exams, the top one-fifth of students in the study scored around 90 percent no matter the methodology. The bottom one-fifth of students, however, performed significantly better when reviewing digital models. Across the three exams, those students’ test scores increased; on one test, average scores jumped from an F to a low C when students were asked to identify anatomical structures on a digital model versus a cadaver.

Over all, the students in the study scored the highest when quizzed on preserved samples. The study was published in Clinical Anatomy, a journal of anatomical associations in Britain, New Zealand, South Africa and the U.S.

Michael Miller, a professor of anatomical sciences at the Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine at Middletown, who wrote the report, said the findings highlight the benefits of teaching a topic through repetition and from different perspectives. Miller said he teaches anatomy using the three methods explored in the study. Students in his classes spend four hours a week in laboratory sessions -- two hours dissecting real cadavers, and an hour each reviewing digital models and samples preserved in a process known as plastination.

“One way or another, we can get through to the student to have them appreciate anatomical structures,” Miller said in an interview. “We were just tapping into a different modality.”

The findings are an early and encouraging sign for medical schools, which often struggle to acquire cadavers needed for crucial hands-on anatomy lessons. New York, where several of Touro’s campuses are located, last year banned the use of unclaimed bodies as cadavers in medical schools, for example.

Most of the state’s medical schools are now running their own body donation programs to ensure their students are able to learn about anatomy by dissecting real human tissue. Students at the Middletown campus dissect 12 cadavers a year; the Harlem campus, 33, said Kenneth J. Steier, dean of Touro Middletown.

“We would certainly like more, but it’s limited,” Steier said in an interview. “You have to balance the need for scientific and educational research versus the rights of families and the rights of bodies. You have to be sensitive to that.”

The findings should also come as welcome news to the med schools -- including Touro -- that have over the last few years reformed how they teach medicine with an emphasis on digital education. The study suggests that, by doing so, they aren’t hurting their students’ chances academically or professionally.

Touro began flipping its classrooms -- delivering lectures in the form of videos students watch on their own time -- in 2010, and switched to an all-flipped model in 2012. Since then, Touro has seen students’ first-time pass rate on a national board exam increase by nearly 20 percentage points. It now sits at around 95 percent, higher than the national average.

Steier said he believes Touro’s move to a flipped-classroom model is the main reason for the increase in test scores. The generation of students entering med school today grew up communicating with others, entertaining themselves and learning using computers, smartphones and tablets, he said, and they seem to be responding positively when their education includes more than labs and lectures.

“They expect technology,” Steier said. “A school that does not embrace new technology is maybe going to be left behind. You’ve got to change with the times.”

Both Miller and Steier said digital models can’t completely replace cadavers, however. Miller said each of the three different ways to teach anatomy comes with its own strengths and weaknesses. Digital models, for example, are only as flexible as the developer allows. Cadavers, once dissected, can’t be reused. And while plastinated samples may be carefully preserved, they are only useful for observing body parts, not learning how to dissect them.

The technology behind digital models is also at the moment more expensive than real cadavers, which cost a couple of thousand dollars to acquire between administrative costs, freezing and transportation, Steier said. Altogether, the computer system at the Middletown campus cost more than $1 million, he said.

Additionally, dissecting a cadaver teaches students about more than just anatomy, Steier said.

“Students have to learn how to respect a body and the variation between bodies,” Steier said. “Handling human tissue properly, maintaining and respecting it -- there’s a whole culture that goes with it.”

Digital models, in comparison, are idealized versions of what anatomical structures look like, Steier said. “It’s like looking at the 3-D projection of a new car. They spin it around, and it looks perfect. Then you go look at it, and there’s a dent. The color’s not right. It could be dirty.”