You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Handshake

College career centers are seeing big boosts in interactions between students and potential employers -- a development they credit to Handshake, a talent-recruitment start-up. But many students who have profiles on the platform say they don’t remember listing their grades or even signing up, and some privacy experts are raising questions about the site's terms of service.

Handshake was founded in 2014 by three engineering students at Michigan Technological University in an effort to give students access to a larger number of potential employers, no matter their location, head of business Jonathan Stull and co-founder Garrett Lord said in an interview.

Lord said he founded the company because of a problem many of his classmates at Michigan Tech faced: the university is located in the state’s Upper Peninsula, a quarter of a day’s drive from Minneapolis and Milwaukee. “A lot of my smart, talented computer science friends didn’t have the opportunities that my West Coast, East Coast friends were having,” he said.

For students, Handshake works a lot like LinkedIn, the professional networking site. Students can build profiles highlighting their academic accomplishments, skills and extracurricular activities, and then make those profiles visible to companies on Handshake that have connected with their university.

Inside Higher Ed on Monday morning activated an account and invited 10 universities to connect on Handshake. Within three hours, six universities approved the requests, granting a reporter access to more than 47,700 student profiles.

Many students appear to have spent time and effort fleshing out their profiles, adding head shots, student clubs, work experience and other pieces of information designed to market themselves to potential employers.

But many other students appear never to have touched their profiles. Those profiles contain only basic information such as major, year and intended graduation date, and, in the case of many universities, grade point average.

Some of those students, contacted by Inside Higher Ed, said they were not aware of Handshake.

“I do not remember even signing up for the service, let alone allowing it to list my GPA,” a former student at the University of Rochester said in an email.

A student at Emory University said the same: “I do not remember giving Handshake permission to list my GPA.”

A recent alumnus of Boston University added, “I wouldn’t know how to take [the information] off, because I don’t remember signing up.”

Disclosing information about thousands of students’ grades without their written consent would be a violation of the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. When reached for comment, however, the universities all said the same thing: at some point, the students gave Handshake permission to display that information.

"Based on the University of Rochester’s agreement with Handshake, a student’s information is only available to potential employers after the student signs up for the Handshake system," a spokesperson for the University of Rochester said in an email. "Once students join, they can customize the settings of their profile according to their privacy preferences. Without a University of Rochester student’s active permission, employers are not able to view that student’s details through Handshake, including his or her GPA."

Following the requests for comment, three of the universities revoked Inside Higher Ed’s access to student profiles.

‘A Huge Win for Students and Employers’

Handshake has gained traction over the last three years. Now headquartered in San Francisco, the start-up has raised $34 million in venture capital funding, according to Crunchbase. Today, more than 160 colleges use the start-up’s platform to run their career centers.

Colleges typically see the number of companies interacting with students double or triple after switching to Handshake, and a 30-40 percent increase in students interacting with the career center, Lord said.

The University of California, Berkeley, began using Handshake in 2016. Thomas C. Devlin, executive director of the career center, said in an email that the platform “substantially increases student engagement with the career center.” He was traveling and could not provide exact numbers, but added, “Simply, we find Handshake to be the new superhighway for career-minded students.”

The University of San Francisco plans to make the switch to Handshake on June 1, said Alex Hochman, senior director of the career services center there. The center made the decision after consulting with Berkeley, Stanford University, Villanova University and other Handshake customers, he said.

“The feedback that I got was that Handshake is a huge win for students and employers,” Hochman said in an email. “They all said that student engagement was 30 percent-plus higher, and that they were seeing a large increase in employers on campus.”

Handshake also touts the benefit it offers to employers. Box, an online storage provider based in the Redwood City, Calif., in 2016 used the platform to hire three students from Morehouse College, a historically black institution in Atlanta.

When a college begins using Handshake, it uses software provided by the start-up to upload basic information about students -- first and last names, year, major, and so on -- and keep it up-to-date. The information remains private until students activate their accounts, Lord and Stull said. Some institutions, like Villanova, include student GPA in that upload; others, like Princeton University, do not, they said.

“When [it is] uploaded, never, ever is that that student information ever shown to anybody else outside the career center,” Lord said. “The only time a student profile -- name, GPA -- is shown to an employer is when a student logs into Handshake and goes through an onboarding process.”

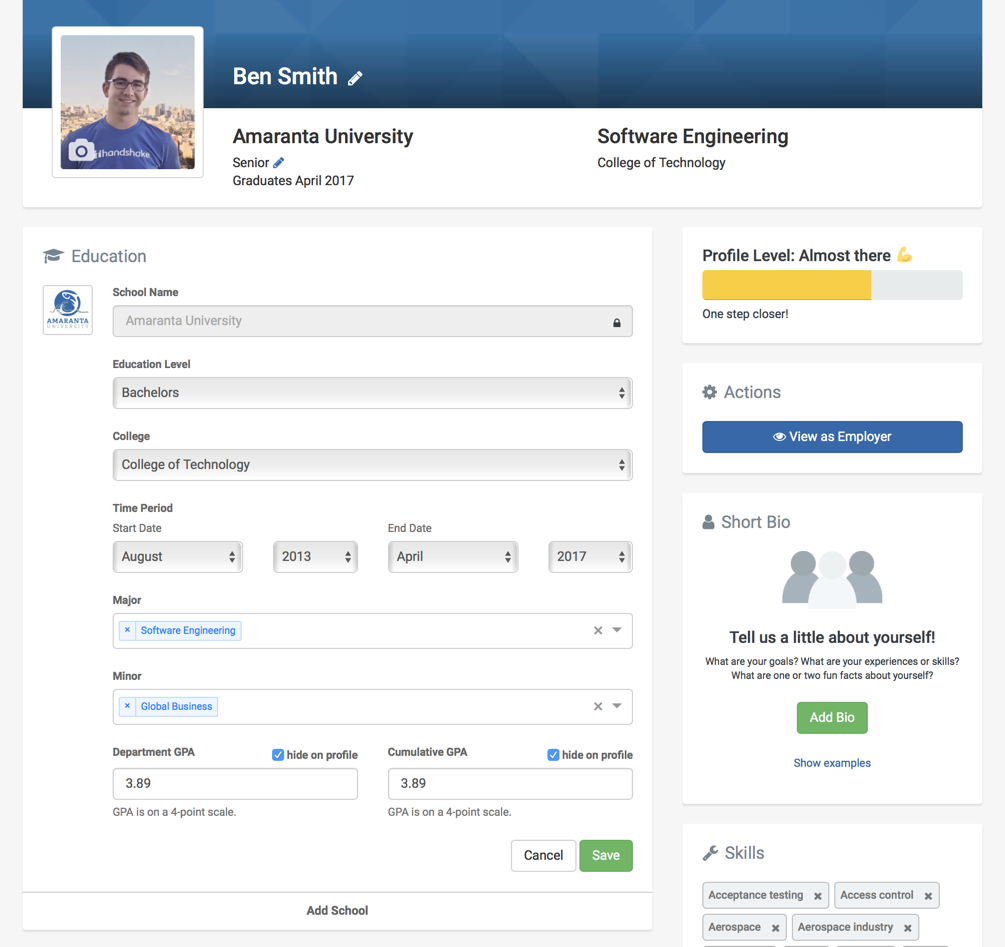

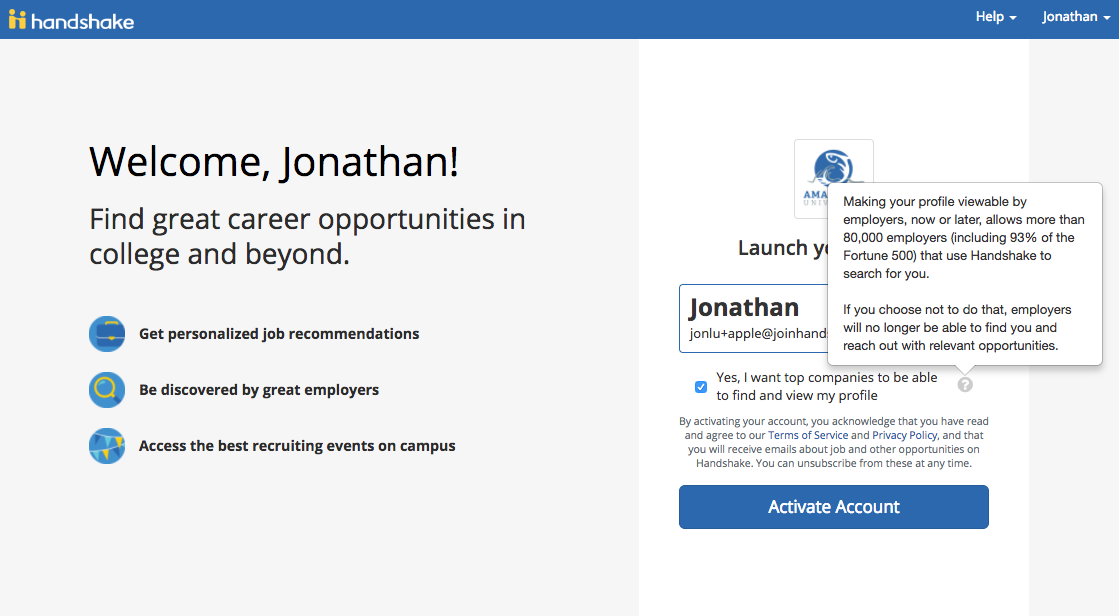

Lord and Stull shared screenshots of the onboarding process. Students are first asked whether they want to make their profile public or private, then about where in the U.S. they could see themselves working, their skills and extracurricular activities. Finally, students are given an opportunity to edit their profiles, which includes checking boxes to hide their cumulative and department GPAs (that information is visible by default).

Lord and Stull shared screenshots of the onboarding process. Students are first asked whether they want to make their profile public or private, then about where in the U.S. they could see themselves working, their skills and extracurricular activities. Finally, students are given an opportunity to edit their profiles, which includes checking boxes to hide their cumulative and department GPAs (that information is visible by default).

Only about 24 percent of students who chose to make their profiles public hide their GPA, Stull said. Most students on Handshake have public profiles, he added -- just 9 percent of students have private profiles.

“There would be no situation where a student would have information released about them without their explicit consent,” Lord said.

‘Committed to Make It as Clear as Possible’

It could be that the students surprised to find themselves listed on Handshake simply forgot that they signed up. Perhaps they did it as freshmen, quickly clicking through the onboarding process without reading the instructions. Another culprit: not reading the terms of service, an issue so common that South Park once built an episode around it.

However, LeRoy Rooker, who for two decades headed the U.S. Department of Education’s Family Policy Compliance Office, which oversees FERPA, said in an interview that the specific language in the terms of service, combined with fact that colleges upload information about students, is important.

In an interview, Rooker pointed out that Handshake’s terms of service state that users “agree that [the] company may share your personally identifiable information, contact details, education history and grades, and other information you enter through the services with your school(s) and potential employers.”

In other words, students agree to share information that they themselves entered, not the college.

“If the student puts it in there, then it’s fine,” Rooker, a senior fellow with the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers, said. “But if [Handshake is] getting this from the school and putting it out there, then that’s where the consent needs to come into play.”

Elana Zeide, a privacy expert based at the Princeton Center for Information Technology Policy, said in an email that Rooker has an interesting point, and that “it would matter if [Handshake] got a particular type of data from the college that was not specified in the terms of service [or] privacy policy and students didn't enter the same piece of information, and then the company shared that with employers.”

Steven J. McDonald, general counsel at the Rhode Island School of Design, said that language, while not perfect, suggests Handshake is “on the right path” to complying with FERPA.

"I assume that the [terms of service] is an effort to obtain student consent for Handshake to then share that information with employers (just as schools themselves would need such consent)," McDonald said in an email.

Coincidentally, Lord said, Handshake is preparing to update its terms of service ahead of the National Association of Colleges and Employers conference in June to make them easier for the average user to understand.

“If it’s not as clear as it should be today, we’re committed to make it as clear as possible,” Stull said. “It is 100 percent our intent that students are 100 percent in control of their data.”

Since Handshake’s platform has been active for only two years, the start-up has not yet performed a purge of accounts that appear to be inactive. Stull said the company may do so in the future.

“We don’t want students on the system who aren’t getting value out of it,” he said.