You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

Politicians often cite skyrocketing debt as a prime reason why students aren’t purchasing homes, but a new report suggests otherwise.

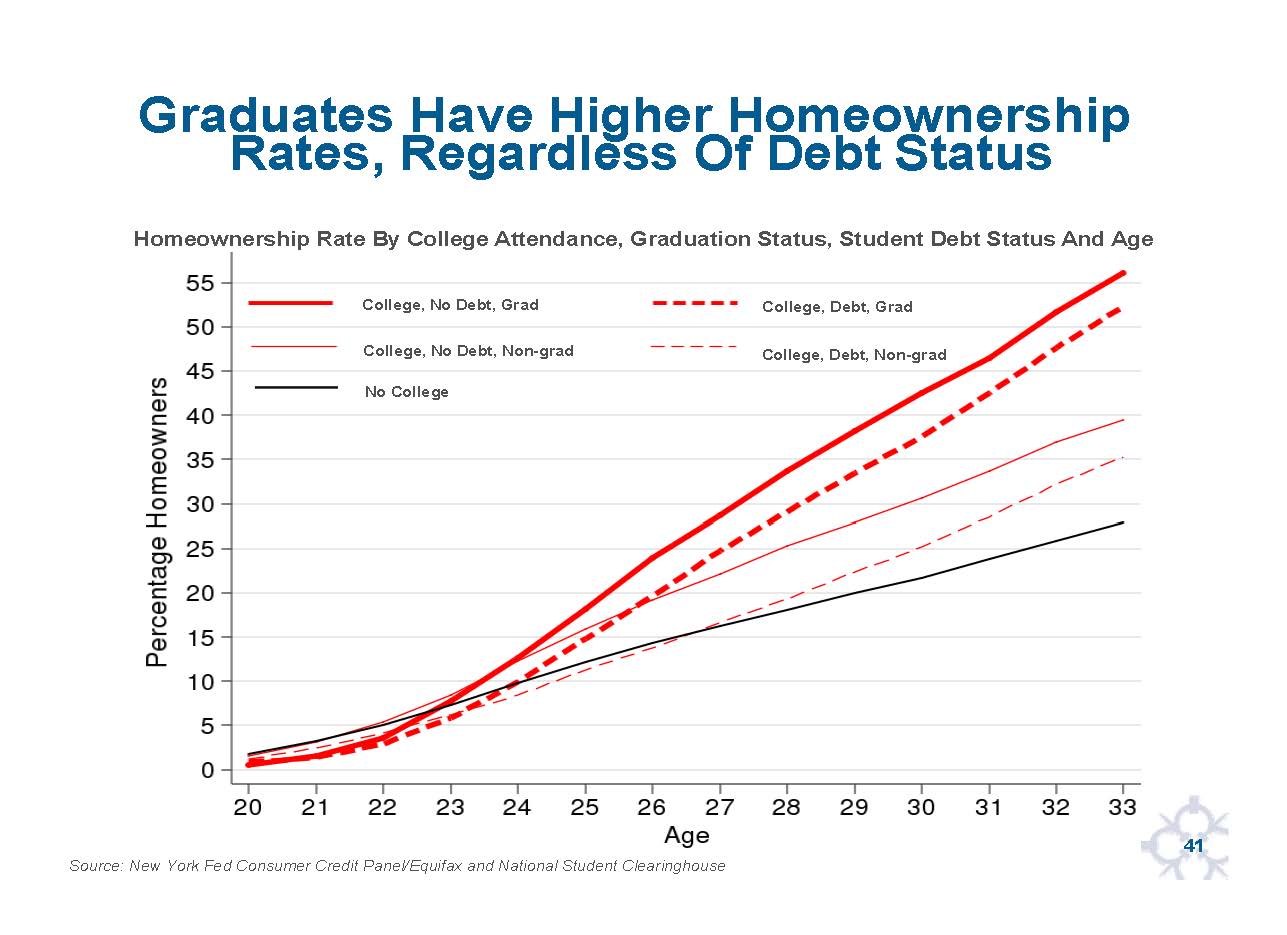

Whether students attend college at all plays a far greater role in determining the likelihood they’ll buy a home later in life, the report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York indicates. Home ownership rates are higher among college graduates and those who have pursued credentials beyond an associate degree, regardless of how much debt they’ve accrued.

By age 33, approximately 56 percent of the debt-free college graduates the report’s authors studied had bought a home; graduates who were still paying off loans trailed by just about three percentage points.

A far greater discrepancy exists between students who attained a bachelor’s degree or higher, and those who only earned an associate degree or didn’t enroll in a postsecondary institution.

A little more than 40 percent of students with an associate degree and no debt were home owners by 33, 10 percentage points lower than those with a bachelor’s degree or more and no debt.

Only about 27 percent of those who never attended college were home owners by that age.

“Home ownership is positively associated with educational attainment -- in terms of both degrees pursued and degrees completed,” the report’s authors wrote in a Monday blog post. “This finding underscores the critical importance of making college financially accessible.”

“Home ownership is positively associated with educational attainment -- in terms of both degrees pursued and degrees completed,” the report’s authors wrote in a Monday blog post. “This finding underscores the critical importance of making college financially accessible.”

The authors couched the report with a note in the blog post saying that while the statistics did suggest certain trends, they don’t necessarily imply causation.

For this reason, few conclusions can be drawn from this particular report, said Rohit Chopra, a senior fellow with the Consumer Federation of America. Often college graduates with homes come from more affluent backgrounds, Chopra said. And of course students who don’t go to college are disadvantaged in many ways, including in home buying, he said.

Conversations have trended toward focusing more on college completion than student debt, Chopra said.

“But that ignores the fact that financial issues are often a major contributor for dropping out of college,” Chopra said. “So financial hardships … can be a big obstacle in getting to the finish.”

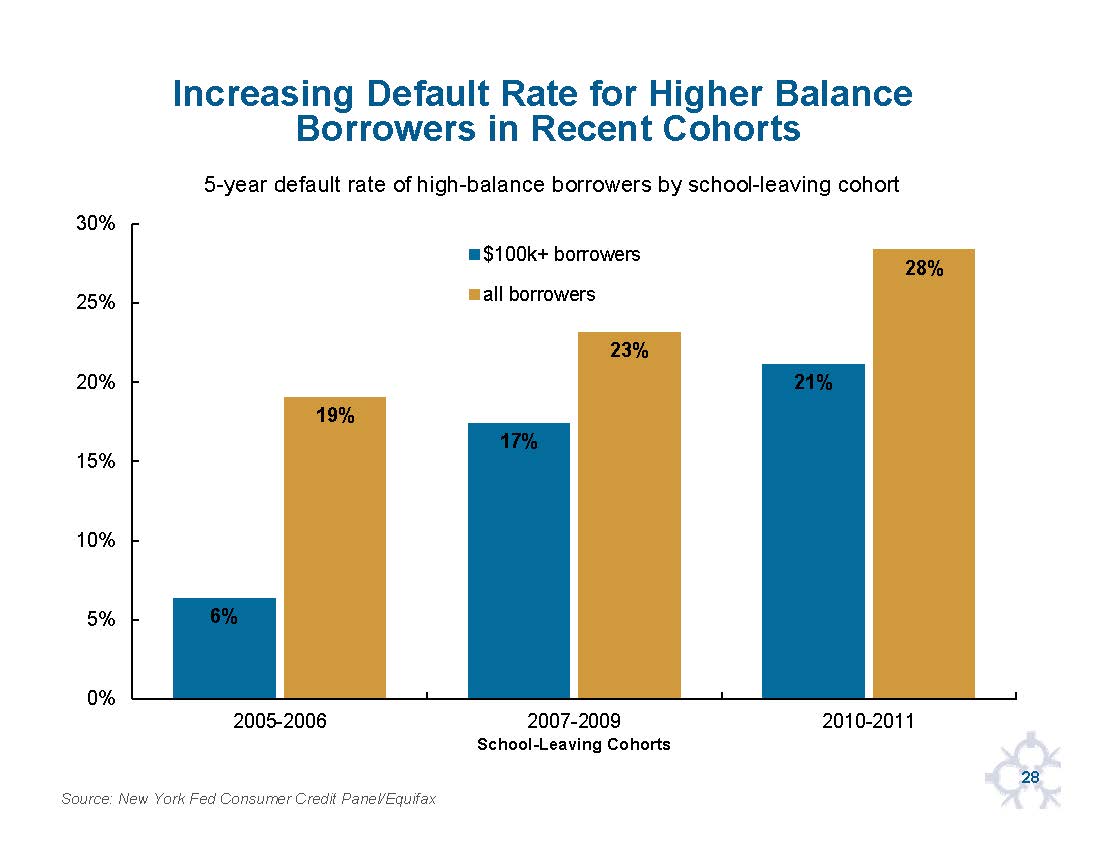

Additionally, adjusted for inflation, wages for young college graduates have been plummeting for years, he said. He pointed out another part of the report that showed that borrowers with $100,000 or more in college-related loans are defaulting more frequently. The percentage of these high-balance borrowers defaulting jumped from 6 percent in 2005-6 to 21 percent in 2010-11. Out of the 44 million borrowers in 2016, however, only 5 percent had more than $100,00 in debt.

This doesn’t bode well, and it’s crushing young graduates’ credit scores, Chopra said.

Robert Kelchen, an assistant professor of higher education at Seton Hall University, said in an interview that the loan delinquency rate for the high-balance borrowers is particularly concerning, considering the prevalence of plans that allow students to pay back loans based on their income.

“I’m just surprised by the magnitude” of the increase in delinquencies for those borrowers, he said.

The authors examined a sample of individuals born between 1980 and 1986, relying on the National Student Clearinghouse and a Federal Reserve Bank of New York database that contains longitudinal information about consumer debt and credit. They defined home ownership as having a mortgage.

A similar 2016 study by the Brookings Institution backs up the New York Fed's recent findings on home ownership.

At the time, the author of the Brookings study, Susan M. Dynarski, a professor of public policy, education and economics at the University of Michigan, wrote that the Federal Reserve Bank had actually spurred fears with another blog post that promulgated the idea that during the Great Recession, home ownership rates among those with debt fell drastically, compared to those without it.

This was not an accurate depiction, Dynarski wrote. She noted that the Federal Reserve Bank failed to separate out students who never borrowed money in the first place and those who never attended college.

For that study, the bank used credit reports but did not match it with the Clearinghouse data.

“Credit reports do contain detailed information about debt, including student loans, mortgages, credit cards and car loans,” Dynarski wrote. ”But they say little about the borrower herself. In particular, they include zero information about education.”

The authors of the recent study in their Monday blog post acknowledged the bank’s past report that Dynarski referenced, writing that that research had not been able to “disentangle” how earning different degrees and the amount of the debt students incurred affected their ability to buy a home later.