You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The Westminster Schola Cantorum is one of three curricular choirs at Westminster Choir College, which has been roiled by debate over whether it will have to move from its longtime campus.

Rider University

Laura Brooks Rice remembers being overwhelmed on her first day as a faculty member at Westminster Choir College.

It was 1985, and the college was holding its opening convocation in the Bristol Chapel on campus in Princeton, N.J. Attendees began singing, as is traditional at the choir college’s events. Rice recalls their voices rising for the hymn “Come, Labor On” and “The Lord Bless You and Keep You,” also known as the Lutkin Benediction.

She was amazed.

“I’ve never been in an institution where people knew to go into four-part harmony,” said Rice, who is a professor of voice at Westminster. “It’s such an amazing thing to experience that sense of knowing each other, knowing what to do.”

Rice’s story is one of many she and other faculty members can tell about Westminster, a college deeply proud of its extensive history. The college’s choirs have performed under a long list of prestigious conductors and with major orchestras from across the country and around the world. Faculty members tell stories of preparing for those performances on the college’s 23-acre campus. It is clear they believe in a special bond with the grounds.

“People feel it,” Rice said. “People remember it. It is a sacred place because of the level of music making that has happened here.”

The bond continued even after financially strapped Westminster merged into better-off Rider College in 1992. Westminster continued operating on its own campus, about seven miles away from Rider’s much larger Lawrenceville location.

So perhaps it should not have come as a surprise that faculty members, students and alumni recently fought the idea of moving Westminster away from its longtime home. They spent the last several months resisting such a relocation after their parent institution -- known today as Rider University and now facing its own financial struggles -- said it was examining moving Westminster to Lawrenceville as part of cost-cutting efforts.

Westminster’s backers secured a temporary stay on the push to move the college late last month when Rider announced it would instead try to sell the choir college. But the uncertainty over Westminster’s future is far from over. Rider’s administration is still seeking significant changes to address budget gaps, enrollment struggles and rising tuition discounting. While university leaders would prefer to sell Westminster and its land as a package, they will consider divesting of them separately if necessary -- a move that would most likely require the college to relocate its operations.

The decision to openly sell a nonprofit college and its land is all but unheard of in higher education. It is also noteworthy in light of current trends toward consolidations between colleges and universities that are seeking to overcome financial difficulties and meet changing student demands. Some wonder if the situation at Rider and Westminster could be a harbinger of a future where changes in higher education don’t just take the form of programmatic tweaks, closures and mergers, but instead assume a wider range of forms including asset sales, spin-offs and a frequently changing stream of affiliations.

The decision to openly sell a nonprofit college and its land is all but unheard of in higher education. It is also noteworthy in light of current trends toward consolidations between colleges and universities that are seeking to overcome financial difficulties and meet changing student demands. Some wonder if the situation at Rider and Westminster could be a harbinger of a future where changes in higher education don’t just take the form of programmatic tweaks, closures and mergers, but instead assume a wider range of forms including asset sales, spin-offs and a frequently changing stream of affiliations.

“This is such virgin territory,” said Rider President Gregory G. Dell’Omo. “These kinds of transactions don’t take place, although it’s going to probably become more common in the future than it currently is.”

Together for 25 Years

Fully understanding the cracks in the union between Rider and Westminster today requires a knowledge of the circumstances under which they were wed. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Westminster, an independent college tracing its history back to the 1920s, faced an existential crisis. It was saddled with falling enrollment, degenerating facilities in Princeton and heavy debt. One college official would later recall that she had an announcement sitting ready on her desk to say that the college would be going into bankruptcy.

Several institutions reportedly expressed interest in a merger, including Drew University, Yale University and the Juilliard School of the Performing Arts. Rider, which was a fast-growing college known for its business school, ultimately became the merging partner. Officials at the time said Rider won over Westminster because of its nearby location and strong financial position -- and because it was willing to allow the choir college to stay in Princeton. The merger took place in 1992 after a year of affiliation.

“The Rider board took a calculated risk by assuming Westminster’s debts,” Rider’s president at the time, J. Barton Luedeke, told The New York Times. Rider would go on to achieve university status in 1994.

By 1996, officials told the Times that Westminster, which had 350 students, was not losing money. They discussed some cost cutting that had taken place at Westminster, but by all accounts Rider put money into the choir college’s campus and facilities and raised its faculty members’ pay over time. It also gave Westminster access to the benefits of scale.

“Rider eliminated the need to have a separate admissions office, a separate finance office, a separate financial aid office,” said John Wilson, president and CEO of the Association of Independent Colleges and Universities in New Jersey. “All of those things were improvements so that Westminster could concentrate on what it does best, which is to educate people for music careers.” (Update: While the head of Westminster admissions and financial aid reports to a senior Rider administrator, there is still a physical office on the Princeton campus.)

Still, the idea of moving Westminster the roughly seven miles from Princeton to Lawrenceville surfaced with relative frequency. Officials have considered a move numerous times over the years, and the market value of Westminster’s Princeton campus, estimated in the millions, has often been mentioned. But so has the potentially greater expense of moving Westminster’s pianos and pipe organs, and of building facilities in Lawrenceville that would be soundproof and acoustically appropriate.

Westminster never moved. But the idea of relocating it to Lawrenceville surfaced again in late 2016, just over a year after Dell’Omo took over as Rider’s president. The university is no longer a growing institution flush with cash. Now it is seeking to close projected budget deficits while finding funding to start new programs and stanch a downward flow of enrollment.

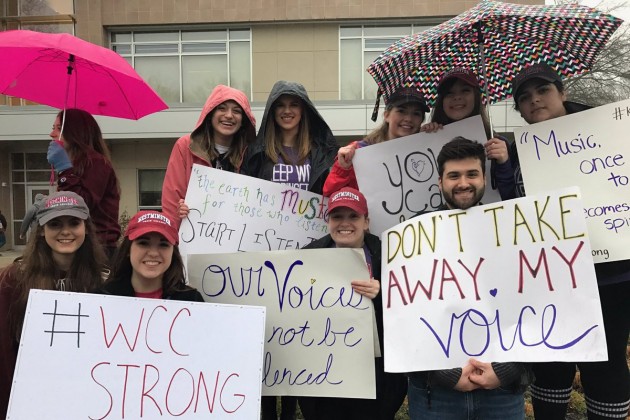

Rider again studied moving Westminster to Lawrenceville. Rounds of protests followed, spilling into 2017. Thousands signed online petitions. A group of alumni and students fought the move with efforts including a 24-hour music marathon.

Rider again studied moving Westminster to Lawrenceville. Rounds of protests followed, spilling into 2017. Thousands signed online petitions. A group of alumni and students fought the move with efforts including a 24-hour music marathon.

Then, at the end of March, Rider announced its decision to sell Westminster instead of moving it to Lawrenceville. The university expects to spend a year trying to make the sale. Leaders say they have been in touch with interested parties but declined to share those parties’ names.

It was a reprieve of sorts for supporters who want to keep Westminster on its longtime campus. It also left Rider, its Board of Trustees and Westminster backers in relatively uncharted territory.

“None of us saw this coming,” said Constance Fee, president of a group called the Coalition to Save Westminster Choir College in Princeton Inc. “I think we are all -- the board, the university, the coalition -- we are all trying to regroup and refocus.”

Fee earned her bachelor’s degree from Westminster and went on to a multiyear opera career in Europe. Today, she is the director of vocal studies at Roberts Wesleyan College outside of Rochester, N.Y. She is also the president of the Alumni Association of Westminster Choir College.

The idea of moving Westminster from its current campus is like the idea of uprooting a tree, Fee said. It might be technically possible, but she thinks it would also probably be fatal for the university.

The Coalition to Save Westminster Choir College in Princeton wants a seat at the table throughout the upcoming sale process. A year is a deceptively short period of time, Fee said. It could go quickly. She and the coalition are ready to fight against any potential sale that looks like a bad deal from Westminster’s perspective.

“We want Rider to survive and thrive, but they can’t, financially, right now, support us in the way they need to,” she said. “And they need money themselves to save their own institution.”

Breaking Up a University

At its most basic level, the decision to sell Westminster is an attempt to loosen constraints on Rider’s operating budget while also providing an infusion of cash. The university posted a deficit of about $3 million last year and is projecting another deficit this year, Dell’Omo said.

Dell’Omo (left) became Rider’s president in August 2015 after serving as president of Robert Morris University for 10 years, during which time he was credited with fund-raising and building successes, growing enrollment, and swinging Robert Morris from a largely commuter institution to a predominantly residential one. He soon started a strategic planning process at Rider and arrived at the conclusion that the university needs to deal with both long-term and short-term challenges.

Dell’Omo (left) became Rider’s president in August 2015 after serving as president of Robert Morris University for 10 years, during which time he was credited with fund-raising and building successes, growing enrollment, and swinging Robert Morris from a largely commuter institution to a predominantly residential one. He soon started a strategic planning process at Rider and arrived at the conclusion that the university needs to deal with both long-term and short-term challenges.

Rider's full-time undergraduate enrollment peaked in 2009 at about 4,000 students, Dell’Omo said. It has since fallen by several hundred students -- a troubling trend at a tuition-dependent university like Rider, even though the university has another 1,200 graduate students.

When Dell’Omo arrived at Rider, the freshman class was about 865, he said. The 2016 freshman class was 880, and the 2017 freshman class is looking like it could be even larger. But Dell’Omo wants to grow the class to 1,000 if possible.

The current growth in freshman class size has also come with a trade-off: increased tuition discounting. In 2016, the university’s freshman discount rate was 53 percent -- the university’s posted tuition and fees for the 2016-17 year total $39,080. The incoming freshman class will likely have a tuition discount rate of about 57 percent.

“If we don’t do some new things, restructure some things, we know we’re going to have deficits running out for probably a number of years,” Dell’Omo said. “That’s just not sustainable. It’s not appropriate.”

On top of those pressures, Rider faces high costs compared to other universities, Dell’Omo said. He’s looking into ways to save. Shortly after he arrived, Rider moved to cut majors and jobs but changed course after faculty balked at the plans. The university’s faculty union instead agreed to concessions and a two-year wage freeze.

Even as the budget tightens, Rider needs cash to develop high-demand programs in areas like science, engineering and technology, Dell’Omo said. It needs to invest in its residence halls and academic facilities.

“It becomes pretty apparent we have to do things differently, both the cost side of the equation as well as revenue enhancement of the university, new programs and other ways we might be able to monetize some of our assets,” Dell’Omo said.

The situation has contributed to high tensions between Rider’s president and unionized faculty members. The faculty union is preparing for a vote of no confidence in Dell’Omo next week. Faculty members are concerned about a number of issues, such as the near layoffs in 2015. Their current contract also expires at the end of August.

Faculty members’ mood is “pretty dim,” according to Art Taylor, an information systems professor at Rider and the president of the university’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors. He did point out, though, that some faculty members have defended Dell’Omo.

There is nothing unique about disagreements between faculty members and administrations at colleges and universities. Nor is it odd to see colleges and universities trying to balance budget cuts against the need to spend to grow revenue in the current environment. Rider joins a host of other universities in walking that tightrope, including another private liberal arts institution in New Jersey that is struggling with its budget, Drew University.

What is different about Rider, however, is its new approach with Westminster. It is virtually unprecedented for a nonprofit university to put a college up for sale, Taylor said.

“In higher ed, the reason you’ve never heard of that is because people don’t buy programs,” Taylor said. “Certainly they might acquire them, take them on. But based on my research and research of other AAUP leaders, there’s just no record of anybody exchanging cash.”

Questions remain about whether Westminster is too expensive for Rider to operate. University administrators have never offered a detailed public disclosure laying out the costs associated with running the choir college, Taylor said.

Westminster isn’t a major drain on Rider’s overall finances, but it typically runs at a deficit, Dell’Omo said. Separate campuses are expensive to maintain, although the president declined to share the exact size of Westminster’s deficits.

It is common for for-profit companies to acquire businesses, hold them for several years, and then spin them off or flip them to another owner, said Larry Ladd, national director for the higher education practice at accounting and advising firm Grant Thornton. Merger-and-acquisition activity was also high among for-profit higher education operators before the for-profit sector crashed, he said. Large for-profit operators have completed acquisitions and sales around the world.

Nonprofit higher education in the United States is a different story. Issues with institutional values make mergers harder to consider and complete. Those factors also make mergers harder to reverse.

“It’s not about the business case, it’s about the identity and mission,” Ladd said. “And so the ones that have become part of larger institutions have become convinced they have no viable path to sustainability.”

Ladd resisted the idea that Rider’s attempt to move on from Westminster signals a failed merger. The combination seemed to work for a quarter of a century, he said.

“Presumably, for many years, this was a success for Rider, but times have changed,” Ladd said. “It doesn’t say mergers are failing. It says mergers can succeed or fail. Or mergers can succeed at one point.”

What Happens Next?

The sudden uncertainty surrounding Westminster’s campus and its future comes at a time when many of the choir college’s faculty members had been feeling optimistic. They acknowledged that music education is highly labor-intensive, even for higher education. And they acknowledged that graduates may have fewer job prospects than they did decades ago as funding for the arts is in flux nationally, the number of traditional churches dwindles and music education often finds itself on the chopping block.

Even so, several faculty members said Westminster’s finances appeared more stable than they were 25 years ago. The choir college, which had no endowment to speak of in the 1980s, now has an endowment of about $20 million -- part of Rider’s approximately $50 million overall endowment. The choir college enrolls 320 undergraduates and 119 graduate students. Faculty members say they’ve adapted to prepare students for the challenges of today’s musical world.

Further, the Princeton campus has seen an infusion of donor money in recent years. It has led to millions of dollars in renovations and the construction in 2014 of the first new building to go up on campus in almost 40 years.

“In the last couple of years, for our campus, it’s been just a boom,” said Joel Phillips, a professor of composition and music theory. “We have the international acclaim we’ve always had. If anything, it’s better than it’s ever been. We’re really sort of at the top of our game right now.”

Speculation over how the college and campus will be sold is developing. The Times of Trenton editorial board suggested nearby Princeton University should buy Westminster and its campus, although a Princeton spokesperson told the newspaper the move was not in line with its mission. Princeton Public Schools signaled interest in buying the choir college’s campus, but that would likely require Westminster’s operations to move elsewhere. Dell'Omo told The Philadelphia Inquirer when the decision to seek a sale was announced that Rider would search for a nonprofit institution but that international and for-profit operations could also be considered.

Such a move would be expensive, Phillips said. Westminster has well over 100 pianos, multiple pipe organs and several rehearsal spaces that would be hard to move or duplicate.

Such a move would be expensive, Phillips said. Westminster has well over 100 pianos, multiple pipe organs and several rehearsal spaces that would be hard to move or duplicate.

“The appropriate facilities would probably cost $60 million,” Phillips said. “There is literally no place you could put us unless somebody said, ‘Two years from now we’ll open a $60 million facility.’”

Fee, the president of the Coalition to Save Westminster Choir College in Princeton, would not rule out the possibility of Westminster continuing to operate on its campus under a different model. When asked whether she thought the college could survive as a stand-alone institution, she said it would have to work with other organizations. Westminster could theoretically draw needed operational support from a foundation, a wealthy donor or another institution, she said.

Although Westminster has spent the majority of its history in Princeton, it should be noted that the college has moved in its past. It traces its history to the founding of the Westminster Choir at a Presbyterian church in Dayton, Ohio, in 1920. Westminster Choir College was established and moved to Ithaca College in upstate New York in 1929. It moved again to Princeton in 1932.

There is also some recent precedent for institutions trying to sell campuses. For instance, Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School last year agreed to sell its 24-acre upstate New York campus, which had become too large for its operations. A development company buying the property recently shared plans to construct a new building on the grounds and lease space there to the divinity school by the start of the 2018 academic year. Developers also want to convert an existing four-story Gothic building on campus into a hotel. But Westminster finds itself in a different situation since, as part of a larger university, it does not control its own campus and potential sale conditions.

Westminster’s faculty members, meanwhile, say they will work to attract new students and keep the college where it is. The message is clear: come, labor on.

“We’re going to be here next year,” said Rice, the professor of voice. “I firmly believe we’re going to be here after that. I don’t have a crystal ball, but I do have faith.”