You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

Attracting students with tuition discounting has its limits -- and one study suggests a surprisingly large number of small colleges and universities are flirting with those limits.

The study, which is being presented Friday at the American Educational Research Association’s annual meeting, looks at the practice and effects of tuition discounting over 10 years at a group of 448 small liberal arts colleges across the country. Tuition discount rates have risen substantially as institutions offer larger and larger scholarships and grants to students in order to entice them to enroll.

Colleges and universities use tuition discounting as they try to meet enrollment goals and increase net tuition revenue. Under the strategy, institutions offer grant aid to some students in order to lower those students’ cost of attendance. The idea is that the grant aid entices students to enroll who would not have attended if an institution was charging more.

By targeting grant aid to certain students, an institution can theoretically meet its goals -- whether those goals are to enroll more students with top test scores, enroll more students from low-income families, enroll more minority students or simply increase revenue by enrolling more students.

But a large amount of the money institutions spend on grant aid is unfunded or unrestricted, meaning it comes from general funds -- which in turn largely come from tuition revenue. So colleges and universities have to strike a balance between their quoted tuition and the amount they discount to ensure they can bring in enough revenue.

Steep discounting can throw off that balance. And the study suggests many universities have waded into levels of steep discounting.

At a certain point, net tuition revenue per full-time equivalent student decreases as unrestricted tuition discount rates increase, according to the study. That point averaged 28.7 percent over the study’s 10-year period.

And 60 percent of colleges and universities in the study averaged unrestricted tuition discount rates of more than 28.7 percent, the study found. In other words, six out of 10 institutions had tuition discount rates that put them at risk for losing net revenue per full-time equivalent for every new student they enroll.

It's worth noting that the study focuses on unrestricted discounting instead of restricted discounting, which is funded by accounts or gifts specifically marked for student financial aid. Rates of restricted discounting changed little during the time period examined. The study's focus and a different sample of institutions examined likely contributed to a difference from higher average institutional discount rates quoted in the National Association of College and University Business Officers' annual Tuition Discounting Study.

The new data suggest a point at which increasing tuition discounting can impede enrollment goals and place institutions’ financial stability in jeopardy, the study's authors said. But in a world where colleges and universities are competing for students, most can’t walk away from discounting as an enrollment strategy.

“There does not seem to be a clear way for institutions to continue to do this going forward on reputation without significant consequences lying ahead,” said Luke Behaunek, the study’s lead author. “But there also doesn’t seem to be a great way to move back from it, and I think that’s how we’ve gotten to this point.”

Across the 448 institutions studied, average net tuition revenue increased 2.3 percent per year. But enrollment grew faster. So did unrestricted grant aid, which grew by more than 6.1 percent annually. Funded grant aid, which comes from sources like endowments and does not affect general funds, held largely steady over the study's time frame, dipping slightly from 8.1 percent in 2003 to 5.8 percent in 2012.

Consequently, growth in net tuition revenue per full-time equivalent only grew 1.26 percent per year.

The study grew out of dissertation work Behaunek did when he was completing his graduate degree in higher education administration. He is now the dean of students at Simpson College, in Iowa.

He cautioned that some institutions can post higher discount rates than others and still be financially successful. Each individual college or university is unique in its market position, published tuition rate it can charge and strategy for divvying up student aid.

“Our data and our model have no way of controlling for the different strategies, marketing campaigns or timing that institutions use to leverage this grant aid,” Behaunek said. “A focus solely on that number is not what’s most important. It’s a reflection of the demands facing that institution.”

Behaunek analyzed institutions by group based on how much they discount tuition. The 10 percent of institutions that posted the highest tuition discount rates had essentially the same net tuition revenue per student as the 10 percent of institutions with the lowest discount rates -- about $13,500.

But the institutions with the lowest discount rates enrolled more minority students and students receiving Pell Grants, which is considered a proxy for students from low-income families. Those with the lowest discount rates had student bodies that were nearly 60 percent minority and almost 70 percent receiving Pell Grants, while those with the highest discount rates had student bodies that were 26.2 percent minority and 38 percent receiving Pell grants.

Researchers wondered whether poor and minority student populations would have increased at high-discount, high-tuition institutions if more colleges and universities had found a way to keep their sticker prices lower. Many students are dissuaded from even applying to a college when they see a high sticker price, said Ann M. Gansemer-Topf, an assistant professor in higher education at Iowa State University and a co-author of the paper. Gansemer-Topf, who chaired Behaunek’s dissertation committee, is presenting the paper at the AERA annual meeting.

“We forget that students, particularly first-generation, underrepresented students, are really impacted by sticker prices,” Gansemer-Topf said.

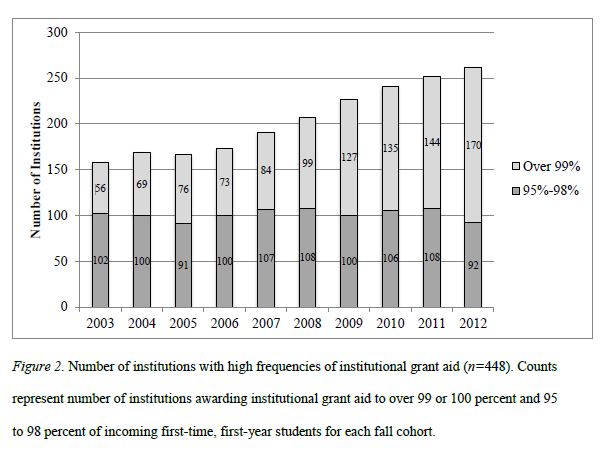

There are indications that an increasing number of colleges and universities have maxed out their ability to increase their discount rates. In 2003, only 56 colleges and universities in the study gave institutional grant aid to 99 percent or 100 percent of their incoming first-year students. That was just 12.5 percent of the number of institutions studied. In 2012, 170 institutions awarded grant aid to 99 percent or 100 percent of incoming first-year freshmen -- 38 percent of the institutions studied.

Researchers observed several other changes to key metrics over the study’s 10-year time frame. The average number of applicants increased by more than 57 percent, to 2,574 per institution. But the average yield rate fell 10 percent to only 31 percent, indicating a lower percentage of admitted students enrolled. Average SAT scores also dropped.

The average enrollment for each fall cohort of first-time freshmen crept up from 338 to 352. The portion of minority students increased from 24.8 percent to 32.8 percent. The portion of Pell Grant recipients rose from 38 percent to 42 percent.

Tuition at institutions in the study averaged $22,529 in 2003. It averaged $27,052 in 2012. But average net tuition revenue per full time equivalent only grew from $14,468 to $16,203.

So some institutions were able to increase their net tuition revenue per student, even as unrestricted discounting increased.

If done well, targeted discounting will increase total net tuition even if net tuition per student falls, said Robert Massa, senior vice president for enrollment and institutional planning at Drew University, who has increased discounting to improve enrollment at different stops in his career, including his current position. That’s because it can bring in more students.

“The real problem occurs -- and this is more and more common today -- when an institution increases discounts, whether targeted or not, and enrollment does not increase,” Massa said in an email. “In this scenario, net revenue per student declines and so does total net revenue.”