You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

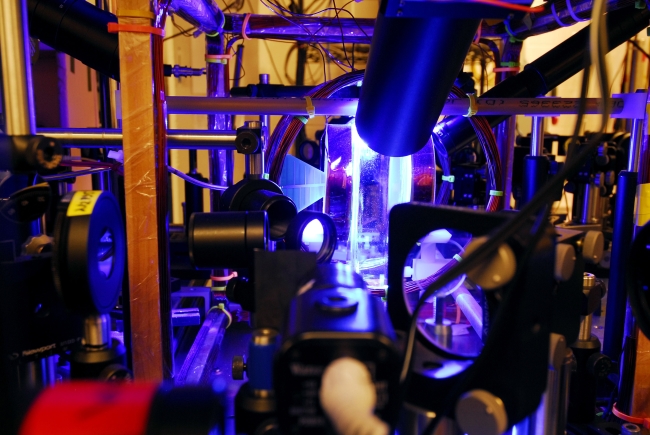

Equipment used to study quantum information systems at Georgia Tech

Georgia Institute of Technology/Gary Meek

Advocates for university-based research are working hard to make sure Congress doesn't buy into what they say is a specious argument made by the Trump administration: that the federal government can cut reimbursement payments to research institutions without undermining the quality of the studies themselves.

In March, after the release of the White House's skinny budget for the 2018 fiscal year, Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price told congressional appropriators that large proposed cuts to the National Institutes of Health could be covered by reducing indirect-cost payments to universities. The complete budget proposal released by the Trump administration last week spelled out those lower reimbursement rates for NIH -- payments for indirect costs would be capped at 10 percent of an NIH grant value. That approach, the administration said, would bring reimbursement rates in line with those made to private foundations.

"Increasing efficiencies within the NIH is a priority of the administration," said budget justification documents released by the White House last week.

To date, Congress hasn’t indicated serious interest in pursuing the kind of major cutback in those payments staked out by the Trump administration in its 2018 budget proposal. A House of Representatives panel on research and technology last week took up the issue of how those indirect costs are negotiated -- a matter that has drawn periodic interest from Capitol Hill.

Republicans on the subcommittee expressed interest in streamlining those facilities and maintenance costs -- often referred to as overhead payments -- to provide more direct funding for research. University representatives cautioned that any reduction in federal funding could result in less research.

Tony DeCrappeo, president of the Council on Governmental Relations, said GOP lawmakers appeared to be in a fact-finding mode in their approach to the issue.

“I didn't hear anyone say [they support] what the budget calls for, which is to dramatically reduce or eliminate payments in order to cut the NIH budget,” he said. “I didn't get that message from anyone.”

Even though lawmakers haven’t endorsed the proposal to cap reimbursement rates, advocates for university-based research are concerned enough about its inclusion in the White House budget that they are actively looking to make the case for the value of those payments. Cutting those payments, they say, is the same thing as reducing support for research, because it would force universities to shoulder more of the costs of experiments.

And there are enough members of Congress elected since the last major fight over indirect costs that advocates see good reason to spend time pushing back against the White House proposal.

“You can’t conduct cutting-edge medical research without high-tech facilities, utilities, hazardous-waste disposal and specialized maintenance and regulatory compliance personnel,” Mary Sue Coleman, president of the Association of American Universities, said of the White House budget. “This proposal guts NIH support for these research costs. If enacted, the proposal will literally turn out the lights in labs where universities have no other funding to pay for these essential research infrastructure and operating expenses.”

Jennifer Poulakidas, vice president for congressional and governmental affairs at the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, said misperceptions remain in Congress about how university research is paid for -- enough for the group to spend serious energy making a case against drastically altering the current reimbursement system.

"It's very much a top-tier concern for us," she said.

Barbara Comstock, a Virginia Republican and chairwoman of the House subcommittee on research and technology, said last week that it was important to see if it’s possible to streamline overhead costs “so that more money can go directly into research.”

Congress and federal watchdogs have periodically taken an interest in questioning how those payments are made and whether the formula for reimbursing universities for research costs should be altered. And the GOP hasn’t been alone in pushing for changes to the current system: the Obama administration said at one point it was considering implementing an unspecified flat rate for all institutions. But after serious pushback by large research universities, it abandoned the idea.

Decades earlier, government auditors found that Stanford University had misused reimbursements to pay for costs related to a yacht and for decorations for its then president’s house. The university saw its reimbursement rate curtailed severely; other institutions made voluntary corrections, and the government implemented a number of new regulations on the payments. Those included a 26 percent cap on administrative costs that applies only to universities and not other grant recipients.

A 2013 Government Accountability Office report found that from 2002 to 2012, the growth of those indirect costs at the National Institutes of Health slightly outpaced that of direct costs over the same period. It recommended that the agency assess how to deal with the growth of those costs potentially limiting funding available for research. NIH argued that those costs have remained a stable percentage of its overall budget.

The House Science, Space and Technology committee has no jurisdiction over the NIH, but it pushed GAO to discuss preliminary findings from an analysis due in the fall of overhead payments to NSF grant recipients. However, John Neumann, director of natural resources and environment at GAO, cautioned that lawmakers should not jump to conclusions about those early findings.

And research advocates counter that those reimbursements don’t come close to covering the full amount universities spend on research costs. A 2015 NSF survey frequently cited by the American Association of Universities found that institutions made $4.9 billion in unreimbursed facilities and administrative expenditures that year.

Each university negotiates reimbursement rates for indirect costs ahead of time with either the NIH or the Office of Naval Research covering periods of three to six years. Those rates vary widely from institution to institution, driven by factors including the type of research work conducted and the geographic location of the campus.

The biggest research powerhouses -- including universities like Harvard, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Johns Hopkins University -- typically negotiate the highest reimbursement rates for indirect costs. Critics of the current indirect costs arrangement say the wide variation of rates is evidence of an unfair system that favors those well-resourced institutions. Comstock said in last week’s hearing that it raises the question “of whether or not we have inadvertently created a system of have and have-nots, where wealthy institutions benefit the most.”

But even leaders at universities with smaller research portfolios say a proposal like the one in the White House budget would have negative effects for all institutions. The University of Oregon is in the midst of building a new research campus, using a $500 million gift from Phil and Penny Knight. David Conover, the university's vice president for research and innovation, said a reduction in reimbursement rates would undermine the whole purpose of investing in those new facilities.

"The university would have no incentive to do what we’re doing in terms of adding buildings and new technology, and bringing in the best scientists the world," he said. "None of that would be feasible if there was no ability to reimburse the university for just a portion of the costs associated with operating the buildings."

DeCrappeo of the Council on Governmental Relations said a flat rate that significantly lowers reimbursements on par with the Trump proposal could conceivably hurt institutions with smaller research portfolios as much as the big-name universities.

“That could create more of a concentration than there currently exists,” he said. “You could argue that a large private institution, if they chose to do so, might be able to withstand that a little bit longer.”

Barry Bozeman, a professor of public affairs at Arizona State University who studies how the federal government funds university-based research, said the current system is archaic but added that the White House proposal is "absolutely draconian and would have disastrous effects.”

And Bozeman said he is skeptical that reductions in indirect cost payments would lead to more funding for researchers themselves. Before changing policy on those reimbursements, he said Congress should commission research on the real costs of university research and the implications of indirect costs for investigators, university budgets and the scientific enterprise as a whole.

"If you're going to keep the doors open at a university, you have to have resources," Bozeman said. "If they don't come from one place, they have to come from another. This is a big resource."