You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

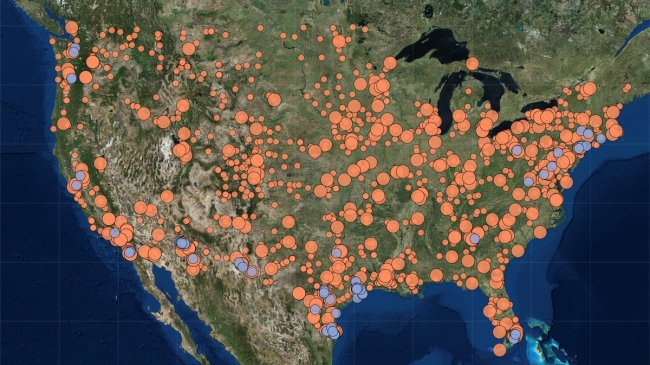

The Torn Apart map shows ICE facilities as orange dots and private juvenile detention centers as blue dots.

Torn Apart

As stories of immigrant children separated from their parents after crossing the U.S.-Mexico border dominated headlines last month, one question came up repeatedly: Where are the children being held?

Immigrant rights advocates, civil liberties groups, federal lawmakers and state governors all demanded answers and tried to get the information in their own individual ways. But a team of scholars set out to find out definitively by mapping the locations of federal and private juvenile detention facilities across the country over a six-day period.

Their data mapping project, Torn Apart/Separados, quickly captured the imagination of academics and gained national media attention. Efforts to expand the project and have it peer reviewed are ongoing, and the organizers are seeking volunteers to help.

Roopika Risam, a member of the mapping team and an assistant professor of English at Salem State University, said she anticipated a strong reaction to the project because of the “timely, political and heartbreaking” subject matter. But what Risam did not expect was the strong reaction the project received from other digital humanities scholars and the sense of vindication and validation of the value of their work.

"I was blown away by the overwhelming sense from digital humanities scholars that the project and the Wired article [that ran about the project] has made an important statement about why digital humanities has significant value as a humanistic approach,” she said.

The Wired article described the team behind Torn Apart as "part of a growing vanguard" of interdisciplinary researchers combining "21st-century technical skills and classical research practices to do a new kind of cultural interpretation -- and sometimes activism."

The Torn Apart team themselves are also making the case for the importance of their work, describing it as revealing "a shadowy network of government facilities, subcontractors from the prison-industrial complex, 'non-profit' administrators paid over half a million dollars a year, and religious organizations across the country, that, together, prop up the immigrant detention machine."

The reception to the project is a welcome and unexpected shift; digital humanities scholars are more accustomed to their field being criticized. For example, in a recent article for The Chronicle of Higher Education, literary and legal scholar Stanley Fish described the field as “anti-humanistic” and poor value for money.

“When the considerable machinery of the digital humanities is cranked up, the product it generates is interpretively inert,” wrote Fish.

Risam said other digital humanities scholars now talk about Torn Apart as a response to “hit pieces” on their field. Dhanashree Thorat, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Kansas, described the project in a tweet as “timely, activist and engaged” and “everything that I would like digital humanities to be.”

Bharat Vankat, assistant professor of cultural anthropology at the University of Oregon, tweeted that he had "often had doubts about digital humanities" but that this project had "put them to rest."

Torn Apart is not the first project with a social justice mission that the team has worked on. Columbia University’s Group for Experimental Methods in the Humanities, known as XPMethod, led efforts to map areas of Puerto Rico affected by Hurricane Maria, and to teach coding to inmates at Rikers Island correctional facility, among other projects.

Manan Ahmed, associate professor of history at Columbia, said that he and colleagues Alex Gil and Dennis Tenen founded XPMethod in part in response to “standard critiques” of digital humanities in the academy.

“We think there are better ways of being and doing digital history, digital humanities, activism and scholarship,” said Ahmed.

A focus of XPMethod is “rapid prototyping and deployment,” said Ahmed. Collective research efforts, which involve academics from other institutions as well as artists and activists, are organized into "researchathons" or "mapathons." The group exists on volunteer labor and doesn’t have any formal funding, but it does meet once a week in a space provided by Columbia University Libraries.

Producing results fast is important because many in the group have other academic responsibilities, said Ahmed.

“Speed, minimal computing and collaborative work are things we admire and can find time to do,” he said.

Jacqueline Wernimont, assistant professor of English at Arizona State University and director of Nexus Lab, a digital research co-op that brings together scholars, artists and activists, said that rapid-response style projects like the “amazing and much needed” Torn Apart project are unusual because university systems “aren’t designed to support nimble scholarship” or respond in near real time to human rights crises.

There are, however, a number of “exemplary” digital humanities projects currently underway that, like Torn Apart, are “responding to our contemporary moment,” albeit over longer time scales, she said. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, concerned about what might happen to public climate change data under the Trump administration, set out to copy and store it as part of a project called Data Refuge.

Other projects such as the Latino Pacific Archive and Black Quotidian are responding to the rise of white nationalism by “documenting the long history of everyday contributions by people of color and immigrants here in the U.S.,” said Wernimont.

“There is real depth of work in these areas that I think much of the popular discussion of digital humanities misses,” said Wernimont. “These are all scholars doing innovative digital work, some of it historical and some contemporary, but all in the service of responding to a 21st-century issue or need.”

Wernimont noted that there has always been a social justice element within digital humanities.

“Some of the oldest and most well-known projects like The Orlando Project and the Women Writers Project have always been engaged,” she said. “They are more historically oriented but also addressing a need.”

Maria Cecire, assistant professor of literature at Bard College and founding director of the Center for Experimental Humanities, also works at the intersection of digital humanities and activism. She sees digital humanities as a way of “breaking down boundaries” and engaging with communities that aren’t often heard.

Like Wernimont, Cecire doesn’t consider socially engaged work as something on the fringe of the digital humanities. “A lot of scholars are focusing their work on how to be part of a better world,” she said.

She cites the work of her colleague Susan Merriam as an example. As part of the Experimental Humanities' Digital History Lab, Merriam has been driving around New York State in a "mobile history van" collecting stories from often ignored members of rural and urban communities near Bard's campus. Collection of these “microhistories” isn’t timely in the way that Torn Apart was, but is “timelessly important,” said Cecire, as it recognizes “that people outside the academy are important stakeholders with much to contribute to our humanistic conversations.”