You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

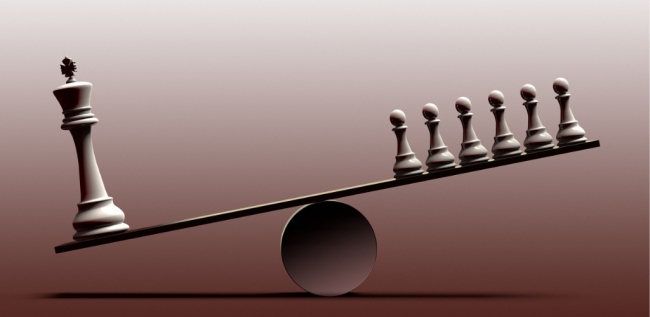

A recently released annual ranking of colleges and universities that produce the most billionaires was hardly surprising. The list included top American institutions with the most selective business schools; Ivy League institutions dominated.

The rankings have remained largely consistent over the years even as the income gap between the rich and poor has widened in the United States. Yet news stories about the institutions that churned out the future billionaires made no mention of this contradiction. The articles were largely laudatory of the financial success of graduates but provided no information about alumni leading socially conscious companies, or working in meaningful jobs where the gap between the highest and lowest paid employees was moderate.

While ranking the rich and famous is common practice in the movie and music industries and is considered innocuous, some scholars are dismayed that similar measurements of wealth have seeped into academe. They worry about the long-term effects the celebratory prism in which rankings of billionaire alumni are presented and sometimes viewed may have on higher ed -- and on students.

“I feel a lot of discomfort with the unabashed celebration of schools bragging about the billionaires they produce,” said Daniel Graff, a labor historian and professor of practice at the University of Notre Dame and director of an interdisciplinary program at its Center for Social Concerns. “It seems to undermine what we’re trying to do in the classroom, which is helping our students form critical perspectives on power and wealth.”

The fixation on the wealth of graduates is occurring as income inequality in the United States “has been growing markedly by every major statistical measure for some 30 years,” according to Inequality.org, a project of the Institute for Policy Studies.

“We’re living in an era of perverse extremes between wealthy people and everyone else,” Graff said. “I guess it’s the new gilded age.”

Graff and other academics are increasingly debating how their institutions -- especially business schools that produce future executives, entrepreneurs and innovators -- should respond and what role they should play in addressing and redressing income equality.

“It seems distasteful to brag about billionaires in era when higher education is relying more and more on billionaires,” he said of the increased reliance on donations from rich philanthropists whose names are then emblazoned on campus buildings. “I’d be interested to see where Notre Dame fits on that list. I have to admit it would be nice if it didn’t appear on that list.”

Notre Dame did not appear in the list of top 10 so-called Billionaire Alma Maters, and neither did several other religiously affiliated universities with well-regarded business schools. But it did make the cut in the top 20 University Ultra High Net Worth Alumni Rankings of 2017. It was ranked 16.

According to the Wealth-X, a self-described “leading global wealth information and insight business” that does the annual rankings, Notre Dame has 277 “known” alumni with a combined wealth of $44 billion. Notre Dame's figure pales in comparison, however, to Harvard University, which was ranked first on the list and has 1,906 known alumni with a combined wealth of $811 billion.

Nonetheless, religiously affiliated business schools appear to be taking the lead in incorporating income inequality as an area of academic inquiry in curriculum and course offerings, seminars, conferences, and community outreach and engagement programs. Their efforts often align with religious social teachings about community service and learning.

Notre Dame’s Mendoza College of Business and the university’s Deloitte Center for Ethical Leadership co-sponsor an annual “Ethics Week” lecture series on themed topics every February. Income inequality will be the theme for 2019.

Selma Botman, provost of Yeshiva University, voiced similar sentiments about Yeshiva’s Sy Syms School of Business.

“We know that people in the business world are confronted with difficult situations all the time and that our graduates will face them, too,” she said. “If we teach them a high level of integrity and to conduct business using Jewish principles of justice, humanity, compassion and service to others, then we’re giving our students the tools to be successful in the business world, in the community and in their family life.”

Still, Graff, who was director of undergraduate studies at Notre Dame for 15 years, is concerned that the increased focus on wealth creation could lead students to view poverty as an unfortunate but acceptable aspect of society.

One of the projects he initiated at the Center for Social Concerns is the Just Wage Working Group, a collaboration of faculty, staff and students to explore workplace issues such as the well-being of workers, discrimination, pay issues and human resource practices as a way of measuring and determining what is a “just wage.”

“My hope is by asking that question that people who are comfortable with their wages see themselves as connected to other people’s wages,” Graff said, adding that high-wage earners should understand the link between their wages and those of low-wage earners. “One of the key things we’re trying to confront is income inequality. Everyone should be invested in people making a living wage.”

Graff tries to incorporate these concepts in the labor courses he teaches.

“An important part of my job is to try to humanize the labor part, the human being who performs the labor,” he said.

The working group held a symposium in Washington in June to introduce and discuss the framework for measuring a just wage. It was attended by scholars and students from various colleges and fields, labor movement activists, worker advocacy groups, and lawmakers. The group hopes to develop an online tool next year that can be used by workers, employers and community members to show how just a wage is.

At Georgetown, Novelli teaches corporate social responsibility, an elective graduate course, and is one of four professors who co-teach Principled Leadership in Business and Society, a cross-disciplinary course required for all M.B.A. students. He also heads the business school’s Global Social Enterprise Initiative, which partners students with corporations, government agencies, nonprofit organizations and career professionals to find solutions to pressing social problems and bring measurable, large-scale and lasting change.

Novelli said 45 students currently participate in the program, which is a small portion of the 996 full-time and evening-class M.B.A. students who were enrolled last spring.

“A lot of students come here and want to go to Wall Street and work at Goldman Sachs and make money,” Novelli said. “It’s true of business students here and everywhere. But we want all the students to leave here with the understanding of the importance of more than one bottom line. We want them to understand that they have social and environmental responsibilities and that that’s compatible with the profit motive.

“It’s not a hard sell,” he said. “They understand it, they believe in it, and they’re game.”

At Yeshiva, these lessons are incorporated across academic disciplines and departments, not necessarily in specific courses focused on income inequality, Botman said.

“We’re not just a university with a business school,” she said. “We train teachers and social workers, psychologists, speech-language pathologists. Our students are bringing to their profession an integrity that emanates from Jewish values.”

For instance, Business as a Human Enterprise, a required course for all first-year honors undergrads in the business school and taught by a Harvard-trained Ph.D. who is also a rabbi, examines the varied roles of business in a democratic society, including corporate social responsibility and social entrepreneurship.

Other undergraduate courses include Social Inequality, Law and Society, and Intermediate Macroeconomics, which examines global inequality across countries. A Labor Economics course focuses on inequalities in human capital, education and wage determination. There’s even an epidemiology course that considers the role of income inequality in health care. The school of social work and the graduate school of psychology also embed discussions about income inequality in their courses, Botman said.

“We don’t believe this issue is an add-on,” she said. “This is core to religiously affiliated institutions, not just us.”

The challenge is engaging students in the search for solutions.

“There’s three ways to go about this,” Novelli said. “One way is to have specific courses, extracurricular activities, seminars and special events focused on income inequality. Another way is to have it as a subject spread throughout the academic program. The third way is to have a hybrid and do both, and that’s what’s happening here and I think more broadly at other universities as well.”

Novelli says poverty and income disparity are subjects that come up often on campus.

“I hear about it both from faculty and students. I think people are concerned about it,” he said. “In our day-to-day conversations, in preparing for classes, in selecting cases to study, we do talk about it.”

Matt Wood, a second-year M.B.A. student at Georgetown, concurred with that assessment.

Matt Wood, a second-year M.B.A. student at Georgetown, concurred with that assessment.

“Just within the curriculum, the professors are often trying to bring up those issues” and encouraging students to be “thinking beyond net present value and profit and thinking about the social implications of business decision making,” he said.

Wood cited a finance class that is a core part of the M.B.A. curriculum as an example.

“When you think about finance, it’s not normal to think about how to use finance to close income inequality,

” he said. But professors use case studies to show how to do just that. For instance, one case study was about growing the income of rural coffee farmers in Africa by providing them access to markets.

“It’s a holistic approach,” Wood said.

That approach was what drew him to Georgetown. He previously worked for a company that did nonprofit and fund-raising strategy consulting for religious institutions and health-care organizations. He also did small business advising and entrepreneurship training as a Peace Corps volunteer in Nicaragua.

“One of the core things I was looking for was business-driven impact and people who are social minded,” he said. “Georgetown kind of checked every box.”

Key among those checked boxes was the campus chapter of Net Impact, a national nonprofit organization for students and professionals who want to use their business skills to support or work on social and environmental causes.

The chapter has a social impact internship fund to help support students working in unpaid “mission-driven” internships. It raised $35,000 to support 10 students this summer.

Charlice Hurst, an assistant professor of management at Notre Dame, said the demands of business school don’t always allow students to easily link their academic pursuits with their socially conscious aspirations.

“There are offsetting messages that kind of contradict the social consciousness message,” Hurst said, noting that business students are repeatedly taught that their primary focus should be on increasing the wealth of their shareholders.

“In finance class that beats out any conversation about income inequality,” she said.

Hurst, a professor in the business school’s Department of Management & Organization, teaches a graduate-level course on social innovation where students are taught how to positively influence society, whether they’re employed at large corporations, nonprofits or running their own businesses.

She said she incorporates the subject of income inequality in her courses “to try and get students to understand how it can affect the operations of their business.”

Fourteen students took the class last semester, a number of them law students.

“It’s hard to even get them to take the class,” she said, noting that those who did take the class loved it. “They have to build up their schedules with classes that make them more employable.”

Hurst said course-load demands sends the message that the university “is not interested in creating social enterprise,” and instead signals “Go get rich so you can then help society.”

“It’s just sad to see super-talented students who are really excited about doing positive things in the world saying, ‘I can’t do anything until I get rich,’” she said.

Balancing the desire to make money with the desire to do good is a conflict many students experience.

“I have students coming to me all the time to talk about this,” Novelli said. “They say, ‘I have student debt. I want to pay it off and I want to make a good living. But I also want to stay engaged. I don’t want to lose this sense of purpose and social responsibility.’”

Hurst said these competing interests are the reasons that most business school students don’t leave college with the idea of tackling income inequality foremost on their minds.

“I think most of them come away with a kind of conventional thinking about business [being] in service of creating more wealth for shareholders,” she said, and that “social responsibility can enhance the bottom line, not because income inequality in and of itself is not moral but because it hurts the bottom line.”

Graff, the Notre Dame professor, said there’s a lot of potential for religiously affiliated colleges and universities to change and broaden students’ thinking and turn them into leaders in the public discourse about income inequality.

“I’ve come to believe over the last 15 years that religious institutions like these are the perfect places to reflect on such issues,” he said. “I’ve increasingly come to see how Catholic social teaching can help fuse spiritual and social questions, especially at Notre Dame, where there have been less problems with budget cuts, et cetera. I feel fortunate to be at a place where the investigation of serious issues can be informed by morality as well as disciplinary perspectives.”

Graff, who has a joint faculty appointment in Notre Dame’s history department and the social research center, directs the Higgins Labor Program, a unit of the Center for Social Concerns focused on teaching, research and community outreach related to work and social justice issues.

“There’s a lot of activism around this issue, but it has been a real challenge to channel that into national momentum that is sustainable,” he said.

Hurst has taught at Notre Dame for the past four years and was part of the Just Wage Working Group. She believes the stated concern about income equality at Notre Dame and elsewhere is often “more style than substance” and is being driven by public relations concerns “because it sounds good and makes the university more marketable and able to differentiate itself in the marketplace to some extent.”

She said courses focused on income inequality have tended to concentrate on poverty in developing countries, even though the university has “pockets of poverty right next door and is a feeder for low-wage jobs.” She cited as an example Business on the Front Lines, a course in the M.B.A. program that examines the impact of business in postconflict societies.

“For some reason we don’t see the poverty right around us,” she said. "Poverty in developing countries is seen as less threatening. Maybe if you’re a major employer paying poverty wages, you don’t want to look at it.”

Hurst said she has not sensed widespread focus on the subject in the business school or across the university.

“I’m sure there are people who think that way, but I have not heard anyone say that on a broad level,” she said. What’s more, “Professors in business schools tend to be more conservative than other departments,” and income inequality “doesn’t seem to be the thing that they want to take up.”

And those who do “understand and care about income inequality on a personal level still may not see it as relevant to their work,” she said.

Hurst also says there’s not enough collaboration among departments on this issue.

“They’re not connected to other disciplines that produce research on income inequality; our research tends to focus inward and not outward at what society is doing, and it’s not looking at the interface between business and society. We’re really not trained to do that.”

She finds the lack of collaboration frustrating.

“I wish there wasn’t so much division or walls between disciplines,” she said. “I’m frustrated that we give such a narrow perspective on business. I think especially at a Catholic institution that stresses morals, students want to be moral but they’re being told no, that’s not what you do in business.”

“The dominant ideology is that we live in a meritocracy, so if you’re poor you must be doing something wrong,” she said. “To Notre Dame’s credit, they have tried to really work on that through its Center for Social Concerns, which even offers faculty training on how to do community engagement,” she said. “But for some reason, it hasn’t penetrated to the business school.”

In the field of management, “there has been more openness to work on class and inequality,” she said. “It’s sort of nascent but we’re starting to see more research on class, but we’re way behind other disciplines.”

At the University of Pennsylvania, which is ranked third on the list of top 10 institutions with billionaire alumni, some 60 students at the Wharton business school took a management course focused on poverty and related social problems last semester.

According to the course syllabus, MGMT 241: Knowledge for Social Impact -- Analyzing Current Issues and Approaches “is designed to provide the information, strategies, examples, and analytical mindset to make students more rigorous, insightful, and effective in analyzing social ills and designing potential solutions.”

The course is taught by Katherine Klein, a professor of management and vice dean of the Wharton Social Impact Initiative, a program that “advances the science and practice of social impact” through research, training and outreach. The course is an undergraduate elective, but many M.B.A. students also enroll in it, she said.

Klein said income equality is the subject of academic inquiry much more than it was 10 years ago. “But do I think there’s enough attention being paid to it? No.”

“A huge amount of what we do is advocate for more attention to these issues,” she said.

Every semester the course focuses on two social problems related to poverty -- it was food insecurity and recidivism last semester -- and examine for-profit and nonprofit strategies to resolve them.

“I think for virtually all of them it’s their first introduction to a rigorous academic look at poverty and mass incarceration,” Klein said. “I would venture to say that a huge percentage of educated adults have no idea what the poverty line is or what it means, so the same thing applies to my students.”

Although Ivy League institutions such as Penn are often considered bastions of rich and privileged young people, Klein said the students in her course are from “quite varied economic backgrounds.”

She describes the class as a deep dive into “the extent of poverty, the experience of poverty.”

“For many students it’s quite eye-opening, and for others it’s closer to how they grew up,” she said.

Klein wants her student to leave her class with more awareness about the complexities of poverty and income inequality.

“I really want them to understand the value and power of research on these issues,” she said. “As much as I love the boldness of business school students and their ambitions, I worry about the arrogance, the thinking that, ‘Oh, I can solve this problem. If only we had good business information about problem X, I can solve it.’ A number of them will go on to work on these kinds of topics, so I want them to have some framework about what works and what doesn’t.”

Novelli said it’s imperative that students understand the socioeconomic and political implications of not addressing income inequality, which he considers “detrimental to a democracy.”

“This is a serious national concern, and I don’t think it’s going to heal itself,” he said. “We have to close that gap, and our students, tomorrow’s leaders, have to focus on it. That’s what I stress in my work.”