You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

More than 40 states have set goals to increase the number of adults who have a college degree or high-quality professional credential within the next few years. But far fewer states have set goals and created policies to close racial equity gaps in pursuit of higher college graduation rates.

Some states, such as Indiana, that did take steps to close these gaps are seeing progress after following through on specific set goals.

Indiana was among the first to adopt a degree-attainment goal focused on equity. Although racial disparities in college attendance and completion rates still persist there, state officials say they have begun to shrink. A state progress report released this month indicates that six-year graduation rates for Hispanic students increased from 47 percent in 2006 to 54 percent in 2011, and from 31 percent to 34 percent for black students. The numbers show solid improvement for sure but still lag behind the 64 percent six-year graduation rate for white students in 2011.

The improved rates have nonetheless met part of a goal set by the state in 2013 to cut racial equity gaps in college achievement by 2018 and to close those gaps by 2025. The state also set a goal for 60 percent of adults to hold a college degree or certificate by 2025.

“It’s clear to us and most states that there is no way to get to those attainment numbers without dealing with equity issues and closing achievement gaps,” said Teresa Lubbers, Indiana's commissioner for higher education. “The good news is that we believe we’re making progress. The challenge is there is still progress to be made, but we have answers to how to go about doing that.”

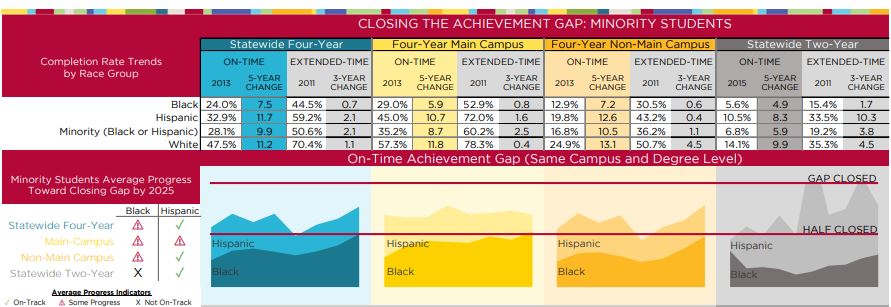

On-time completion rates have increased by more than five percentage points for black and Hispanic students in the past five years at four- and two-year college campuses in the state. On four-year campuses, on-time completion for black students increased by seven percentage points, to 24 percent, and by 12 percentage points, to 32.9 percent, for Hispanic students. On Indiana’s two-year campuses, the on-time completion rate improved by eight percentage points for Hispanics, to 10.5 percent, and by five percentage points for black students, to 5.6 percent.

On-time completion means students earned a degree or certificate within four years at a university or two years at a community college. Despite the progress, there is still a gap between black, Hispanic and white students, who have a 47.5 percent on-time completion rate at the universities and 14.1 percent at the community colleges.

Still, the data also pointed to some troubling outcomes for the state. For example, the only racial equity gap on track to close by 2025 is between Hispanic and white community college students. And on-time completion rates haven’t increased at a level to close all gaps by 2025.

Lubbers said the colleges have a good idea of what works from the performance of students in the state’s 21st Century Scholars Promise Program, which provides merit-based financial aid to first-generation, low-income students and seeks to close performance gaps for students who received free and reduced-price lunch as middle schoolers or are Pell Grant recipients.

From 2012 to 2017, on-time graduation rates for 21st Century Scholars increased by double digits, to 34 percent at four-year colleges and 17 percent at two-year colleges, according to the state. The gaps in on-time completion for scholars at two-year institutions have closed, and the gaps at four-year institutions will nearly close by 2025.

“The success elements we integrate into the scholars program apply to everybody,” Lubbers said, adding that recent reform efforts in the state such as 15 to Finish, which encourages students to pursue 15 college credits a semester in order to graduate on time, and guided pathways and degree maps so students know what is needed to graduate, will help to close racial gaps and improve completion overall.

As for the still low completion numbers, Lubbers said many of these initiatives and programs designed to improve outcomes are still relatively new and haven’t been taken to scale across the colleges.

“One thing about Indiana right now is that we’re willing to try most anything we can to understand how we can move these numbers … not because numbers matter, but people matter,” she said.

Last year, an analysis from Educational Testing Service, the standardized-assessment organization, found that national goals to increase educational attainment among adults would not be met if racial equity gaps were not closed. The report detailed that at the current rate of expansion of the U.S. adult population, and with the current rates of degree attainment, 2041 is the year the federal government’s target could be met.

The federal goal, which was set in 2009 by the Obama administration, is for 60 percent of 24- to 34-year-olds to have earned an associate or bachelor’s degree by 2020. The Lumina Foundation, which has been the leader in helping to establish state goals, has a national benchmark for 60 percent of working-age adults to have a “high-quality” certificate, associate or bachelor’s degree by 2025.

A set of reports released in June by the Education Trust found that gaps between black and white and Latino and white adult students persist nationally. The reports showed that 30.8 percent of black adults and 22.6 percent of Latino adults have earned an associate degree or more, compared to 47.1 percent of white adults between the ages 25 and 64.

“If we’re going to close racial and ethnic gaps in completion, we need to have data disaggregated and have colleges take a bigger role in ensuring students are graduating,” said Will Del Pilar, vice president of higher education policy and practice at Ed Trust.

Holding Institutions Accountable

Del Pilar points to a few other states, such as Texas, Oregon and Colorado, that have examined completion, access, retention and other data points by race and ethnicity, and have set goals for how colleges can make measurable progress.

Colorado, for instance, has a goal for 66 percent of the state’s adults to have a post-high school certificate or degree by 2025. So far only 55 percent of adults in the state hold a degree or certificate.

In 2012, the state had initially set specific goals for decreasing racial equity gaps across each demographic, but by 2017 views in the Colorado Legislature shifted to decreasing all gaps completely.

“Any equity gap is unacceptable,” said Amanda DeLaRosa, chief of staff in the Colorado Department of Higher Education. “So we benchmarked all populations against 66 percent by 2025.”

Colorado is in a unique position. It has the second highest educational attainment rate in the country, at 55.7 percent -- behind Massachusetts at 56.2 percent, according to the Lumina Foundation. But it also has one of the largest gaps in racial equity, DeLaRosa said.

“One of the things to know about Colorado is that we’re really good at importing talent,” she said. “When you look at statewide achievement, the folks with the most degrees came from out of state. You look at homegrown talent and you see equity gaps.”

But the state has started making progress. In 2012, the Hispanic population, which is Colorado’s fastest-growing group, had 18 percent certificate or degree attainment. That rate has increased to 29 percent today but still lags 64 percent of the white population with a certificate or degree. And at the current rate, Colorado is not on track to meet its attainment goal if the racial equity gaps are not erased, DeLaRosa said.

Last year, Colorado required each campus president to set annual goals and detail how they would close their own racial equity gaps. And while that work is relatively new, DeLaRosa said three colleges have started working on initiatives that they expect will help to close those gaps.

The state received $500,000 from the Lumina Foundation’s Talent, Innovation and Equity grant last year to target gaps at Community College of Aurora, Pueblo Community College and Colorado State University Pueblo. CSU Pueblo, for instance, is using a portion of the money to partner with high schools and create student success classes for 11th and 12th graders. Community College of Aurora has a plan to put faculty through boot camps that track student performance after each exam or lecture. They plan to disaggregate the data by race and examine how instructors can improve or change their teaching styles based on the results, DeLaRosa said.

The biggest challenge for the state is in spreading these initiatives beyond just a few colleges.

“If we can be more effective in taking what we’ve learned from pilot [programs] and years of experience and scale that to all institutions using existing dollars, that’s where we’ll find out greatest success,” she said.

Del Pilar said states that haven’t set goals to increase completion rates or close equity gaps pose an even bigger problem. He points to California, which has a 35-percentage-point gap between white and Latino students in degree attainment. Only 18.3 percent of Latino adults in the state have a certificate or degree, according to Ed Trust.

A coalition of colleges, nonprofit organizations and education foundations have called on the next California governor to set a degree-attainment goal for the state and to close racial equity gaps in college achievement by 2030.

“If we’re not explicit that we need to do a better job at improving college preparation and graduation rates for these diverse student populations, it simply won’t happen,” said Michele Siqueiros, president of the Campaign for College Opportunity, which is one of the groups calling for the attainment goals.

There is a perception that California is progressive on a lot of issues, including racial equity, Siqueiros said.

“I remind people that no, even in California, our leaders lack the courage to talk about race and equity that takes responsibility for what our state and colleges can do better,” she said.

Meanwhile, more than 50 percent of students in the K-12 system are Latino, Siqueiros said.

“It isn’t simply about improving college graduation rates for Latinx, black and Asian American students,” she said. “It’s about what does the future of California look like economically if we don’t do a good job educating our diverse population.”