You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Does a professor have a right to refuse to write a recommendation for a student due to his own political convictions?

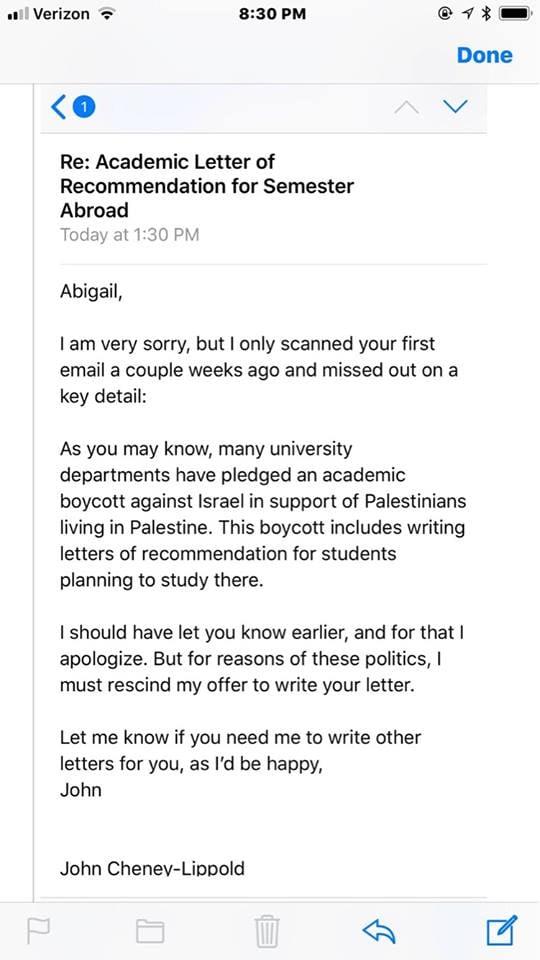

A professor at the University of Michigan declined to write a recommendation for a student to study abroad upon realizing the student’s chosen program was in Israel. In an email to the student, which was posted as a screenshot (at left) on Facebook by the pro-Israel group Club Z and was first reported by Israeli media, the professor cites support for the boycott of Israeli academic institutions as the reason why he was rescinding an offer to write a recommendation letter. At the same time he indicated he would be happy to write other letters for the student, who is identified only as “Abigail.”

A professor at the University of Michigan declined to write a recommendation for a student to study abroad upon realizing the student’s chosen program was in Israel. In an email to the student, which was posted as a screenshot (at left) on Facebook by the pro-Israel group Club Z and was first reported by Israeli media, the professor cites support for the boycott of Israeli academic institutions as the reason why he was rescinding an offer to write a recommendation letter. At the same time he indicated he would be happy to write other letters for the student, who is identified only as “Abigail.”

"As you may know, many university departments have pledged an academic boycott against Israel in support of Palestinians living in Palestine," says the email from John Cheney-Lippold, an associate professor in the American culture and digital studies department at Michigan. "This boycott includes writing letters of recommendation for students planning to study there."

"I should have let you know earlier, and for that I apologize. But for reasons of these politics, I must rescind my offer to write your letter."

"Let me know if you need me to write other letters for you, as I'd be happy," the email concludes.

“I firmly stand by the decision because I stand against inequality, I stand against oppression and occupation, I stand against apartheid and I use that word very, very seriously," Cheney-Lippold said in a phone interview with Inside Higher Ed.

He confirmed that he sent the email but clarified that he made a mistake in saying that many university departments have supported the boycott against Israeli universities. What he should have said is that many individual professors do.

Cheney-Lippold said it is appropriate for professors' political and ethical stances to inform their choices of whether and when to write letters on their students' behalf. "The idea of writing a letter of recommendation is a part of being a professor where your own subjectivity comes into play," he said. "I don’t want professors to be seen as just rubber-stamping … A professor should have a decision on how their words will be taken and where their words will go."

"I have extraordinary political and ethical conflict lending my name to helping that student go to that place."

The University of Michigan, for its part, issued a statement affirming its opposition to the boycott of Israeli academic institutions, and clarifying that no academic department or unit has taken a stance in support of it.

"Injecting personal politics into a decision regarding support for our students is counter to our values and expectations as an institution," the university said in a statement issued Tuesday. An earlier statement from the university described the faculty member's decision as "disappointing," but that language was removed from the subsequent statement, which a spokesman said was revised for purposes of concision.

The case raises complex questions for professors about academic freedom and faculty obligations. Generally, most would probably agree that principles of academic freedom give a professor every right to refuse to write a letter on the basis of a student's poor academic performance. But to what extent is writing recommendation letters a faculty duty such that refusing to write one for nonacademic reasons breaks an unwritten social contract? How should institutions balance academic freedom with the expectation that faculty will write letters to support their students' academic goals -- that is, when their performance in the classroom merits it?

The questions at issue are not settled ones, even from the perspective of the main body that advocates for faculty freedoms and rights, the American Association of University Professors. The AAUP has a long-standing policy of opposing academic boycotts.

“In general, AAUP policy does not address whether faculty are obligated to write letters of reference,” said Hans-Joerg Tiede, the associate secretary of the AAUP's Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure and Governance. “I think that it's generally understood that writing such letters falls within the professional duties of faculty members. I also think that it's generally understood that faculty members may decline to write a particular letter in particular instances, for example, because they believe that they have insufficient information on which to base such a letter. In general, refusing to write a letter of reference on grounds that are discriminatory would appear to be at odds with the AAUP’s Statement on Professional Ethics."

John K. Wilson, the co-editor of the AAUP's blog, "Academe," said, "Writing a letter of recommendation is not like teaching a class; it is a voluntary activity, and not a necessary part of one’s academic work. Professors are given broad discretion to decide how, and if, to write a letter. And they can decline if they think the opportunity is not in the best interests of the student, even if the student disagrees."

"However, I think it is morally wrong for professors to impose their political views on student letters of recommendation." Wilson stressed however, that the professor should not be punished. "If a professor was systematically refusing to write letters of recommendation because they are time-consuming and unrewarded in academia, it might be appropriate for colleagues to judge it as a small mark against them on the service criterion. But a singular case like this certainly should not be punished in any way," he said.

Cary Nelson, a former AAUP president and an opponent of the movement to boycott Israeli academic institutions, argued on the other hand that the professor could be punished. "What the professor did violated the student’s academic freedom -- the right to apply to study at any program anywhere in the world," said Nelson, a professor emeritus of English and Jewish culture and society at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Nelson said he believes it is a violation of professional ethics for a professor to decline to write a letter for a student on the basis of politics. A faculty member has the right not to write a recommendation, but not based on political objections to the university or nation in which the student is interested in studying, or the student’s own politics, Nelson argued.

Max Samarov, the executive director of research and campus strategy for StandWithUs, a pro-Israel organization, accused the professor of dereliction of duty. StandWithUs opposes the spread of the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement against Israel on campuses and views BDS as an "expression of the new anti-Semitism that targets the Jewish state instead of Jewish people."

"This professor's job is to help students educate themselves about the world. Refusing to do his job simply because it conflicts with his personal politics is reprehensible. The fact that he did this in service of a discriminatory agenda like BDS only makes it worse," Samarov said.

Reflecting a different view, David Klein, a professor of mathematics at California State University, Northridge, and a member of the organizing collective of the U.S. Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel, argued it was the professor’s prerogative not to write the letter. Klein, who opposes study abroad programming in Israel, said he agreed with Cheney-Lippold's decision.

"First of all, a professor has a right to decline a request to write a letter of recommendation under any circumstances: that’s a choice a professor makes about a student and a goal. In this case I think it’s the ethical thing to do. The study abroad program for Israel is really a propaganda program to legitimize the apartheid system in Israel and I think it’s proper for a professor to object to participate in that," Klein said.

Asked whether a professor’s political views can constitute valid reasons not to write a recommendation, Klein said, “I think that’s a complicated question, because politics is a very broad category. But within politics there are ethical principles, too. Antiracism is a political position, and I think antiracism is a legitimate political position to invoke in situations like this, whereas other more superficial political considerations like Republican versus Democrat would not be appropriate.”

"Study abroad programs in Israel are not open to all U.S. students," said Cynthia Franklin, another member of USACBI's organizing collective and a professor of English at the University of Hawaii. "Israel can and does deny entry to diasporic Palestinian students, as well as to non-Palestinian Muslims and Arabs. Palestinian students are not free to travel in or out of the country to pursue their educational goals."

"Israel's antiboycott laws also mean that they can bar entry to any students who are known for their work supporting the BDS movement," Franklin said.

"As a supporter of the academic boycott, like John Cheney-Lippold, I would decline to write a letter of recommendation for a student applying to a study abroad program in Israel. I could not write such a letter in good conscience, as that would mean that I would be supporting and legitimating an academic program that is discriminatory. This student would, of course, be free to ask for a letter of recommendation from another faculty member."

Cheney-Lippold said he was uncomfortable with the focus being on him and the decision of whether or not to write a recommendation rather than the conditions he sought to draw attention to. "I never wanted to be the story," he said. "I want to be able to use the tactic of a boycott to highlight the apartheid system, to highlight the discrimination that’s happening, to put the spotlight not on a single professor at the University of Michigan, but why might a professor have done this.”

He said he has not heard from the student since he sent the email Sept. 5.