You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions

Trump administration officials say that the rules governing college accreditors have become too prescriptive and too limiting of innovation in higher ed -- a problem they’re trying to tackle by overhauling the regulations for the higher ed watchdogs.

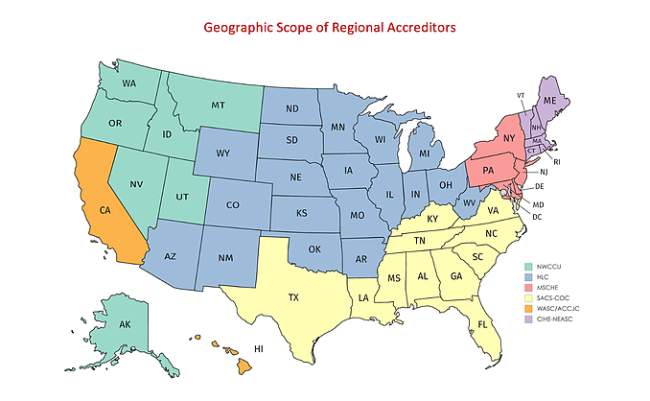

But a proposal offered as part of a regulatory rollback by the Education Department could create huge disruptions for the regional accreditors that oversee more than 3,000 colleges across the country. The department wants to require that regional accreditors operate in no fewer than three but no more than nine contiguous states, a standard multiple organizations would fail to meet.

The issue is among a number of disputed ideas up for consideration during a negotiated rule-making process that has gotten off to a contentious start at the Education Department this week and will continue for the next two months.

For the higher ed stakeholders charged with considering the package of rule changes, it wasn’t clear what problem the idea was supposed to solve. Department officials said their intent was to distinguish between regional and national accreditors -- which largely oversee vocational, career education and for-profit colleges. The proposal reflects the department's view that there is little to distinguish those organizations now besides the types of institutions they serve, a fact that the department says unfairly maligns colleges overseen by national accreditors. The administration's critics, however, saw it as a clumsy swipe at traditional higher ed institutions overseen by regional agencies.

The fight over the proposal also appeared to serve as a proxy for an ongoing dispute over the value of public and nonprofit versus for-profit higher education. National accreditors remain the home to most for-profit colleges, even as some have sought regional accreditation over the past decade. The idea also managed to draw the ire of accreditors and traditional higher ed groups in a process that the department had promised was a boon to the sector.

“My view is that it is not clear what problem you are trying to solve with this. It is also not at all clear what would be gained if your proposal were to be adopted,” Terry Hartle, the senior vice president for government and public affairs at the American Council on Education, said at a rule-making meeting Wednesday. “This is a very big change in an area of accreditation that I submit works reasonably well.”

The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, based in Decatur, Ga., oversees colleges in 11 states, from Texas to Virginia. And the Higher Learning Commission, another regional accreditor based in Chicago, has colleges in 19 states in the Midwest, South and Southwest. Hartle warned that those accreditors would be forced to choose which states to drop, leaving hundreds of schools without recognition. Meanwhile, the WASC Senior College and University Commission, which oversees colleges in California and Hawaii, apparently wouldn't meet the minimum geographic requirements proposed by the department -- although department officials offered to delete wording that would require accreditors to oversee colleges in several "contiguous" states.

A separate change offered by the department would bar regional accreditors from authorizing colleges with a branch campus in a state outside their geographic scope. That means the New England Commission on Higher Education couldn't accredit Northeastern University, for instance, because it operates branch campuses in Seattle and North Carolina.

“You’re creating other national accreditors -- that’s what you’re doing,” said Barbara Gellman-Danley, president of the Higher Learning Commission, at the negotiated rule making. “The cost of this and the chaos would be enormous.”

Hartle and Gellman-Danley are both appointed representatives for the negotiated rule-making process. Their opposition means the department would likely have to drop the proposal if it hopes to get consensus on a slate of changes it's seeking for regulation of accreditors.

Education Department officials said they believe that many regional accreditors are already operating like national oversight bodies because their colleges operate branch campuses in other states as well as international programs. And the department said students who earn credits or degrees at nationally accredited institutions -- often for-profit colleges -- frequently don’t have them recognized by regionally accredited colleges because of biases at those institutions.

“There is not a distinction in the Higher Education Act in quality or prestige between regional accreditation and national accreditation,” said Barbara Hoblitzell, an Education Department official. “We want to try to take that stigma away and help level set accreditation for all institutions.”

Michale McComis, president of national accreditor Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges and another rule-making panelist, said the issue the department identified was a real one for graduates of colleges overseen by the accreditor, who he said are “routinely subject to the kinds of prejudicial and discriminatory behavior that you’ve talked about.”

But Hartle pointed out that credit-transfer policies are set by colleges themselves and not their accreditors. New regulations from the department wouldn’t change that. And the changes advanced by the department would just create uncertainty for those institutions, Hartle said.

Amy Laitinen, director of postsecondary education at New America, said the proposal to flatten the differences between regional and national accreditors is a long-standing ask of for-profit colleges.

“The proposals to gut regional accreditation and further reduce accreditor oversight will create an accreditation-shopping race to the bottom that means more students will be borrowing for meaningless credits,” she said. “That’s not good for students. It’s good for substandard institutions who want to get their hands on federal money.”

The negotiated rule-making process is required to change many of the federal rules governing higher ed. It involves appointing representatives from various interest groups to a panel that will debate proposed changes and aim to reach consensus on new regulations.

The attempt to narrowly define the geographic scope of regional accreditors became a flashpoint of disagreement between department officials and representatives of traditional higher ed on the panel and suggested little chance of an agreement unless it is withdrawn. But the broader package of changes the Trump administration is pursuing would make it easier to approve new accreditors and for existing accreditors to approve new programs. The main rationale, officials said, is to spur more innovation in higher ed.

Department officials, though, struggled this week to explain their reasoning behind specific proposals. One would allow two organizations to "co-accredit" the same college. If one accreditor was federally recognized, that could serve as the basis for the second's federal recognition. The department couldn’t point to any programs that have been denied because of the current standards. And representatives on the panel questioned a proposal that would limit the evidence an accreditor is required to submit to the department establishing wide acceptance of its standards.

Denied a Seat

The first controversy that arose in the rule-making process this week concerned whether state representatives should be seated on the panel. The State Higher Education Executive Officers association and the Maryland attorney general’s office sought places on the negotiated rule-making panel.

But college leaders balked at the inclusion of an attorney general representative, arguing it would create a conflict because those offices have sued higher ed institutions over fraud and abuse.

On Tuesday, there appeared to be agreement among negotiators to add a SHEEO official and a representative from the New York attorney general’s office as a backup. But the Education Department nixed the addition of an AG official.