You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

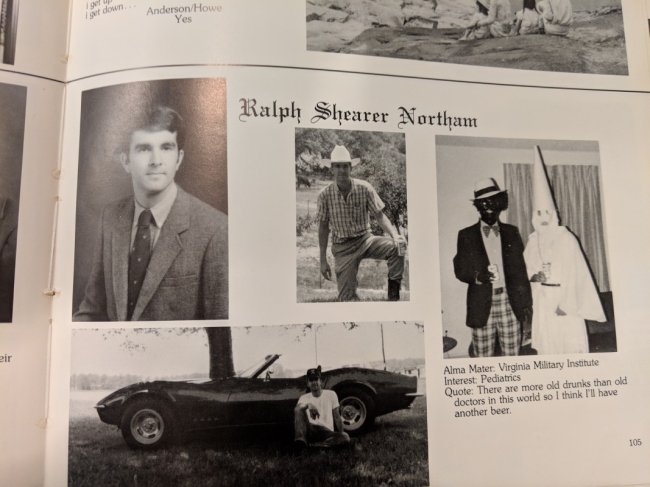

Ralph Northam's yearbook photo from 1984

Getty Images

When Eastern Virginia Medical School published a statement on Saturday about racist photos in the institution’s 1984 yearbook, purportedly of the state’s governor, Ralph Northam, many asked: How could this have been going on? How could the yearbook’s editor allow such blatantly bigoted photo to be published? How could this happen in the 1980s?

The photo, on a page in the yearbook devoted to Northam, depicts two people, one in Ku Klux Klan garb, the other in blackface. While Northam initially took responsibility and said he was one of the two people in the photo, he later backtracked and said he believed it was mistakenly attributed to him. The scandal has resulted in widespread calls for Northam's resignation from lawmakers and pundits of all political stripes, a harsh rebuke of a lawmaker who ran on a platform of racial justice.

But the incident has also prompted those questions to Northam’s alma mater about how it handles racism, both presently and historically, and whether officials there skated over the prejudice that was apparent on campus during Northam’s time. It’s a question more broadly posed to universities -- especially in Virginia, a state steeped in the Confederacy. While debates over monuments to Confederate leaders have been long-standing, the new development in the last few days has been reckoning with more recent history.

Scholars and historians said in interviews with Inside Higher Ed that to truly address the root of racism, colleges must educate their incoming students particularly about the effect that Confederate symbols, or Klan imagery, for instance, can have on campus.

“The bigger issue is systemic,” said Keri Leigh Merritt, a historian on race and class based in Atlanta. “At some point soon we will be forced into a real conversation about what education reparations look like.”

Richard V. Homan, Eastern Virginia’s president and provost, has already pledged that all past yearbooks will be investigated to determine the publishing process and whether administrators were involved in it. Homan banned the yearbooks in 2013 after he was shown that year’s version featuring three white students dressed in Confederate uniforms in front of the Confederate flag, The Washington Post reported. The Richmond Times-Dispatch also interviewed a yearbook page designer from around when Northam was enrolled who said that students submitted the photos that would appear on their personal pages.

The yearbook from 1984 contains other racist references, other photos of blackface, such as a man dressed in a white dress and pearls, a black wig and blackface, with the caption “Baby Love, whoever thought Diana Ross would make it to medical school,” a reference to the lead singer of the Supremes, the black Motown group.

While Northam has most recently denied he was in the photo, at a recent, eyebrow-raising press conference he did admit to using shoe polish to darken his face as part of a Michael Jackson costume, and in an odd aside, added he won the dance contest because of his skills in moonwalking.

A page of Northam’s undergraduate yearbook at Virginia Military Institute from 1981 also lists his nicknames as “goose” and a Jim Crow-era slur, “coonman.” Northam said the latter moniker was given to him by upperclassmen for reasons unknown. A VMI spokesman declined to comment.

Homan on Saturday said in a statement that the yearbook photo that caused the initial stir was “shockingly abhorrent and absolutely antithetical to the principles, morals and values we hold and espouse of our educational research institution and our professions.” Eastern Virginia will hold a news conference today to discuss the yearbook.

“It has been said that those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it,” Homan said in his statement. “We must learn from this and will come together to support and live the values and principles we hold so dear.”

Reaction to Homan’s words has been largely negative, with the public criticizing their hollowness, though alumni have emerged to defend Eastern Virginia. Naved Jafri, who said he graduated from the institution in 1996, wrote on Facebook that he never experienced discrimination when he attended, nor observed anything such as what was present in the yearbook. He declined an interview, but told The News Leader in Staunton, Va., that the photo didn’t accurately depict Eastern Virginia’s culture.

While commentators online seemed shocked that the picture passed editorial muster, Julian Hayter, an associate professor of leadership studies at the University of Richmond, was not surprised at all. Hayter has studied race relations extensively and said that by the '80s, black people had only been part of historically white colleges in any significant numbers for about a decade. Colleges were ill equipped to handle desegregation in the '60s. And in the South, expressions of racism persisted despite the shifting laws, well past when Northam was studying medicine, he said.

“A lot of that has to do with this appalling persistent type of racist imagery that the public has grown accustomed to,” Hayter said.

Racially charged episodes at colleges and universities, blackface in particular, occur frequently. In 1991, seven years after Northam’s photo, fraternity brothers on George Mason University’s campus dressed up in drag and blackface and were put on probation. The next year, a fraternity at Texas Tech University was punished for a party where members wore blackface and afro wigs.

As recently as last year, a California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo fraternity came under fire for blackface. Two women faced wide condemnation at the University of Oklahoma and left the institution in January after a video circulated of one of them in blackface using a racial slur.

Blackface has a particular legacy in Virginia and at its flagship institution, the University of Virginia, according to Rhae Lynn Barnes, an assistant professor of history at Princeton University and an expert in blackface. Barnes did not respond to request for comment but wrote an extensive essay on the subject in the Post.

UVA relied on amateur blackface financially and most prominently during the Reconstruction Era. Students would form “negro minstrel troupes” to perform on campus and in towns -- these were early iterations of blackface, used as a form of entertainment. The university’s official Minstrel Troupe donated proceeds of its show -- featuring a stand-up comedy routine satirizing black politicians -- to the construction of the university’s chapel in 1886, Barnes wrote.

Barnes alleges that the UVA yearbook, Corks and Curls, which is independent from the university, is a reference to the minstrel slang for burned corks, which were used to darken faces, and curly afro wigs that were part of the costumes. A summary of the yearbook's history on its website states that a student actually named it for “an unprepared student” who was called upon in class “but who remained silent like a corked-up bottle.” The curl referred to students who performed well in class, “who, when patted on his head by his professor would curl his metaphorical tail in delight.”

UVA has also commissioned its own report on its association with slavery and found that the campus was largely built by black slaves. The institution documented at least 150 to 200 enslaved people at the university in most years during construction in the early 1800s.

The university is building a Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, which is due to be completed in October, honoring those who helped construct it. The UVA Board of Governors also voted in September 2017 to remove two plaques from the university’s rotunda that honored students and alumni who fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War.

This all came after the white supremacist protests in 2017 over the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee. The protests shifted to the city of Charlottesville, where one woman died, struck by a car driven by a white nationalist.

A UVA spokesman, Anthony de Bruyn, responded to a request for comment by forwarding a campuswide email from President Jim Ryan on the controversy with Northam. Ryan did not explicitly demand that Northam step down, but said that when “trust is lost, for whatever reason, it is exceedingly difficult to continue to lead.”

“It seems we have reached that point,” Ryan wrote in his message, adding that the photo was “shocking.”

Northam will also no longer attend this week's Charter Day event at the College of William and Mary. The president there, Katherine A. Rowe, told the campus Monday that she was “appalled and saddened” by the image from Northam’s yearbook and that his presence would disrupt campus unity and so the college and his office mutually decided he would no longer appear.

William and Mary also removed Confederate imagery from prominent locations on campus in 2015 -- a plaque that listed students and professors who fought for the Confederacy and a ceremonial mace emblazoned with its battle flag.

As two of the older institutions in the state, both UVA and William and Mary have closer ties to the turmoil caused by the Civil War.

James Madison University, meanwhile, was not founded until 1908, but was named for a founding father who was a slave owner.

The Madison Board of Visitors will consider on Friday a proposal to name a new residence hall for Paul Jennings, who was James Madison’s personal manservant.

Jennings was an enslaved black man who served until Madison’s death and later gained his freedom, writing the first memoir about life at the White House, called A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison.

“The naming of the residence hall is just one part of the larger effort of the university to increase understanding of the legacy of James Madison, and of the continuing need to confront our past, present and future with regard to issues of diversity and inclusion,” spokesman Bill Wyatt wrote in an email.

Hayter, of Richmond, said that universities should pursue educational routes to ending racism -- but be more unambiguous if they have a “tortured racial history.” Instead of glossing over a past with slavery, it should be included in an institution’s advertising and officials should spell out how they are addressing it, Hayter said. He recommended that part of institutions’ orientations be devoted to history on race.

“It has to be part of the school’s identity,” Hayter said. “You shouldn’t be blindsided by this stuff; it needs to become part of the university’s DNA, not an addendum to the narrative. Young people need to know what they’re getting into.”