You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Franklin & Marshall College

Franklin & Marshall College is moving to close a budget deficit that has developed in recent years, bringing its finances into focus after receiving accolades for financial aid policies designed to admit talented students regardless of economic background or ability to pay.

The small private liberal arts college in Lancaster, Pa., plans to close a 6 percent budget deficit over two years. It will address about three-quarters of the total deficit, which translates to about $8 million on a $133 million operating budget, in the first year and move on to the remaining quarter of the deficit in the second. Steps to be taken include cutting staff jobs and changing purchasing practices.

Leaders at the college cast the process as healthy for any institution seeking to make sure its financial picture lines up with its values, and they are adamant students’ experiences will not be affected. Franklin & Marshall has a new president, Barbara K. Altmann, who has been engaged in a review of budgeting and budget processes since she started.

But it is impossible to consider Franklin & Marshall’s current budget situation without acknowledging the symbol the college has become in a world of high college sticker prices, rising tuition discounting and struggles over which students should receive financial aid and why. Its former president, Daniel R. Porterfield, has been a leading advocate for bringing more top students onto the college campuses that graduate students at the highest rates -- even if many of those students come from low-income families.

Franklin & Marshall has been highlighted for reallocating funds from non-need-based aid to need-based aid. Today, it advertises itself as basing financial aid solely on need, and it is a member of the American Talent Initiative, a group of colleges and universities seeking to expand college access for low- and moderate-income students. It is not, however, need blind in admissions.

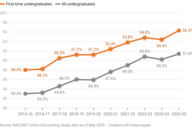

In recent years, the college has been spending more and more on financial aid. In the fiscal year ending in June 2011, just before Porterfield’s inauguration, Franklin & Marshall recorded $99.5 million in tuition and fee revenue and spent $28.6 million in student financial aid, its audited financial statements show. In 2018, it took in $132.6 million in tuition and fees against $56.1 million in financial aid.

That means that although its tuition and fee revenue rose by almost $33.2 million on paper over the seven-year period, the college actually collected only $5.6 million more in net tuition and fee revenue in 2018 than it did in 2011.

Altmann has said that the current budget deficit was partly caused by increased financial aid. But it is not the primary driver of the deficit, she said in a telephone interview Wednesday. The college is not backing away from its commitment to using financial aid to bring in the best and brightest students, no matter their origin, she said.

“One of the primary values here is we want to bring in the best class,” she said. “We are not backing off of that in any way. It’s one of the powerful things that is giving us motivation to clean up the rest of the financial house so we can continue to sustain that.”

However, leaders do want to slow the rate at which tuition and fees have been increasing and hold the college’s tuition discount rate at roughly its current level, between 42 percent and 46 percent, she added.

The cost of educating a student exceeds the amount that can be reclaimed by increasing prices, and that gap must be made up with other revenue sources like the college’s endowment, Altmann said. Realigning the budget can strengthen the college’s footing for the long term, she continued.

While Franklin & Marshall is far from the poorest institution, its endowment does not measure among the largest in the country. It has the 240th-largest endowment in the most recent study from the National Association of College and University Business Officers. The endowment’s market value totaled $352.1 million in 2018, up 3.4 percent from the year before. That works out to about $155,055 per student. A number of top liberal arts colleges comparable in size have endowments of $1 billion or more.

“We offer a really superb undergraduate education,” Altmann said. “The one thing that is holding us back at the moment is we have a smaller per-capita endowment than some of those other schools that are ranked more highly than we are. But there are other schools that are far better endowed than we are that are actually having similar struggles.”

A larger endowment would not be a panacea, of course. And Altmann acknowledged that other private colleges with larger endowments, like Oberlin College, have shown signs of financial pressures rocking the sector in recent years.

That would seem to raise serious questions about the long-term viability of the high-tuition, high-discount model -- particularly for institutions that award aid primarily based on need, instead of using non-need-based aid to chase students who may have less academic prowess but come from wealthy families and would generate more revenue for the colleges where they enroll. They are particularly explosive questions because they lie at the intersection of wealth, privilege, race and opportunity in higher education.

A Franklin & Marshall spokesman said he has heard no discussion of bringing back non-need-based aid at the college.

Franklin & Marshall has often been noted because its student body diversified as it focused on recruiting students based on talent above all else. In 2010, three-quarters of its incoming freshmen were white, 3 percent were African American and 6 percent were Hispanic, The Philadelphia Inquirer noted in 2017. That fall, 57 percent of freshmen were white, 7 percent were African American and 12 percent were Hispanic.

Yet college officials maintain that they focused on bringing in the best students, not on diversity. The fact that students from underrepresented populations enrolled in greater numbers is just a corollary to recruiting talent, Altmann said.

The interactions between talent, diversity, wealth and financial aid create significant challenges for institutions in a world where wealth is increasingly concentrated and the population of high school graduates is rapidly diversifying -- but where many of the new, diverse high school graduates are expected to come from families that are not wealthy.

So backers of educating more students from moderate- and low-income families wonder what else private colleges can do but adopt a model where sticker prices are steep and discount rates are also high.

“What would the alternative be?” asked Catharine Bond Hill, managing director of Ithaka S+R, which collaborated with colleges and universities and the Aspen Institute to create the American Talent Initiative. “To let these schools be high income and not very diverse?”

Doing so would seem to call into question how closely the institutions are following their educational missions, she said. It could also deny many students the chance to attend colleges that have good student outcomes.

“One of the advantages, if we have greater socioeconomic diversity and racial diversity in these institutions, is the really high graduation rates in these schools,” Hill said. “This is a place where students get through. They get a B.A. that really changes their lives.”

Hill was president at Vassar College last decade when it returned to a need-blind policy and adopted a no-loan plan for students from families with incomes up to $60,000. It did so right before the financial crisis, but Vassar stuck with its policies.

It meant adjustments to staffing size, but it was considered important for the overall mission of the institution, Hill said. Other colleges have to find ways to stick with their missions in light of unexpected financial shocks, whether they be recessions, unforeseen changes to admission rates or other variables changing.

“It’s a challenge, because schools are competing not just for talented students with financial need, but also for students who can pay the full price,” Hill said. “You’re deciding on the margin, with every dollar you spend, how this is going to work out for the full pool of talented students you’re trying to recruit. The rising income inequality has made this incredibly hard.”

Porterfield, who left Franklin & Marshall to become president of the Aspen Institute, was traveling and not available for comment Wednesday. Franklin & Marshall’s board chair, Susan L. Washburn, said in an email that the institution is working from a position of strength.

“Record applications,” she wrote. “Outstanding students, faculty and staff. Our goal is to assure financial resilience for the many years ahead.”

Franklin & Marshall hasn’t made a decision about how many positions could be cut to bring the budget in line. Some will be eliminated through attrition. Benefit levels are also being examined.

The college has committed to a recently adopted salary improvement plan designed to bring pay for faculty and professional staff members into the median range for peer groups.

Some trade-offs are off the table, Franklin & Marshall’s current president said.

“We could easily drop our discount rate, but that would compromise the quality of our class, and we’re not willing to do that,” Altmann said. “The quality of our academic programs and the power of our academic programs to launch young graduates into the world is absolutely our primary goal, and we do very, very well there.”