You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

California State Assembly

Wikipedia

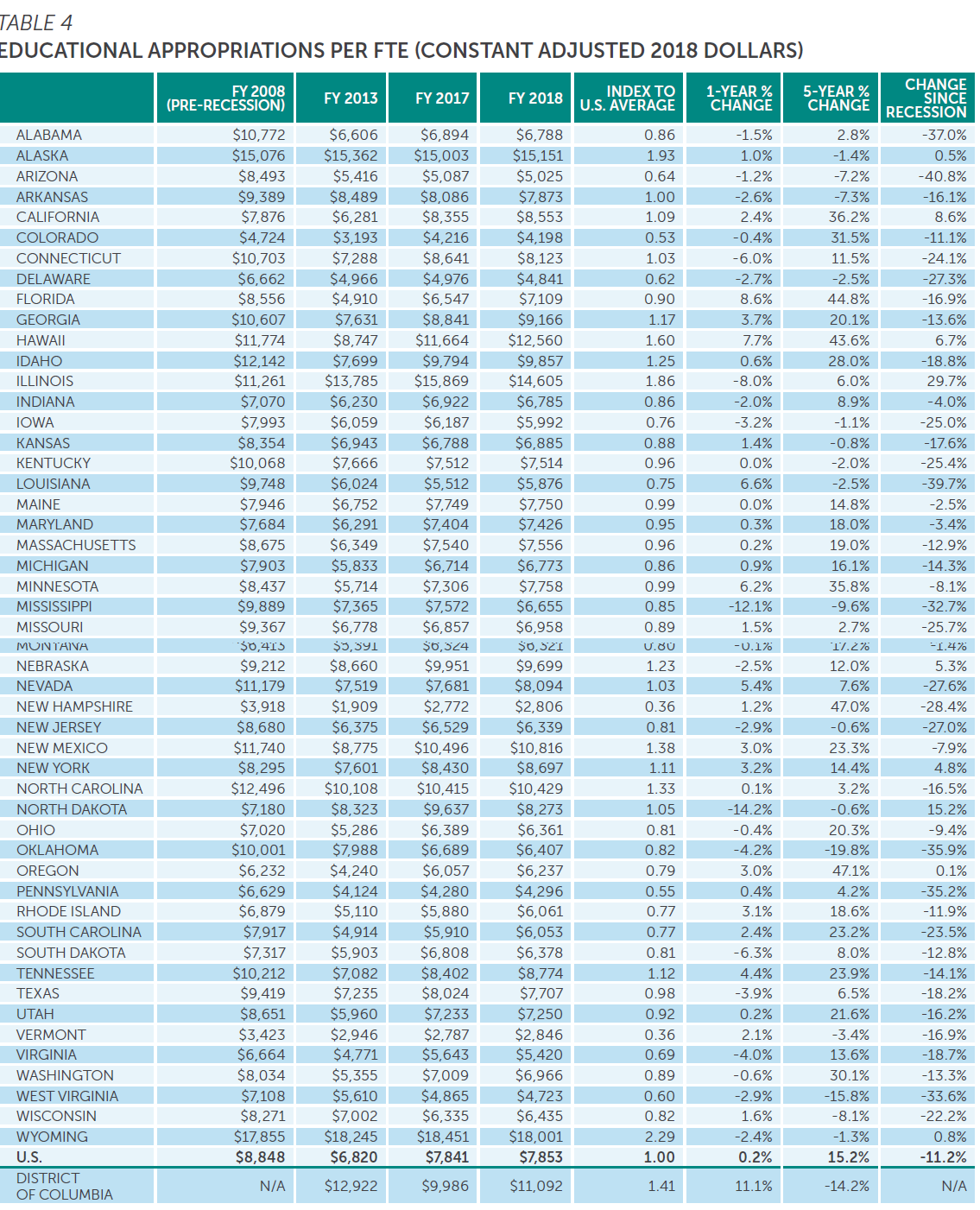

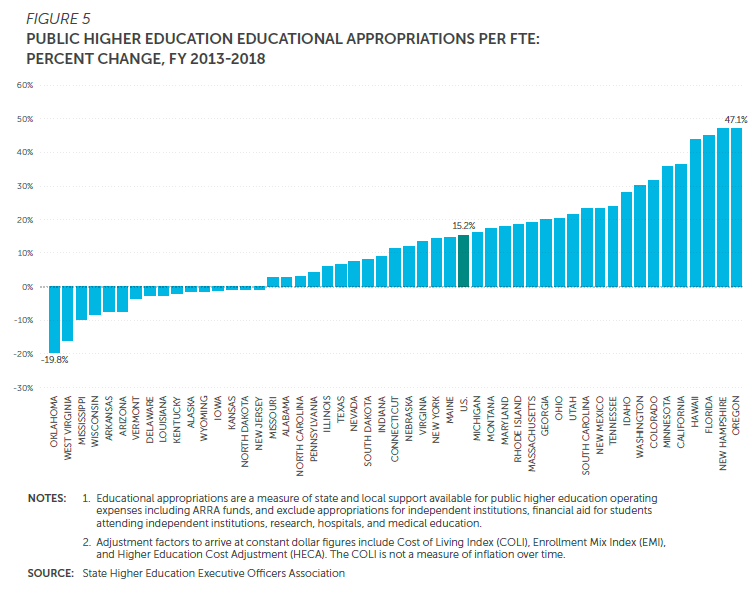

A decade after the 2008 recession, fewer than one in five states has fully recovered when it comes to per-student appropriations for higher education.

A new study finds that just nine states have bounced back from pre-recession funding levels, and another 11 have yet to increase per-student funding to even the low point of the recession.

In the middle: 30 states that have higher per-student appropriations than at their low point in 2012 or 2013, but which now fund postsecondary education at a lower level than their pre-recession high of 2007 or 2008.

The findings suggest that even as many state higher education systems have marked several years of annual funding increases, recovery has been highly uneven and has largely failed to keep up with expanding enrollments over the decade.

The findings are part of the annual "State Higher Education Finance" report, published by the State Higher Education Executive Officers association. The report examines the state of public higher education financing in the most recent fiscal year (2017-18), and this year -- a decade out from the Great Recession -- also explores how public colleges have and have not recovered from that transformative event.

The nine states that have recovered in per-student funding over that decade: Alaska, California, Hawaii, Illinois, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Wisconsin and Wyoming. And even among these nine, caveats apply: in Oregon, for instance, local funding made a difference in what was otherwise flat state-level funding. In two others -- Illinois and North Dakota -- per-student appropriations never declined during the recession. In Illinois, that was due to the state’s efforts to backfill an underfunded pension system, while in North Dakota state appropriations in 2012 were actually higher than in 2008.

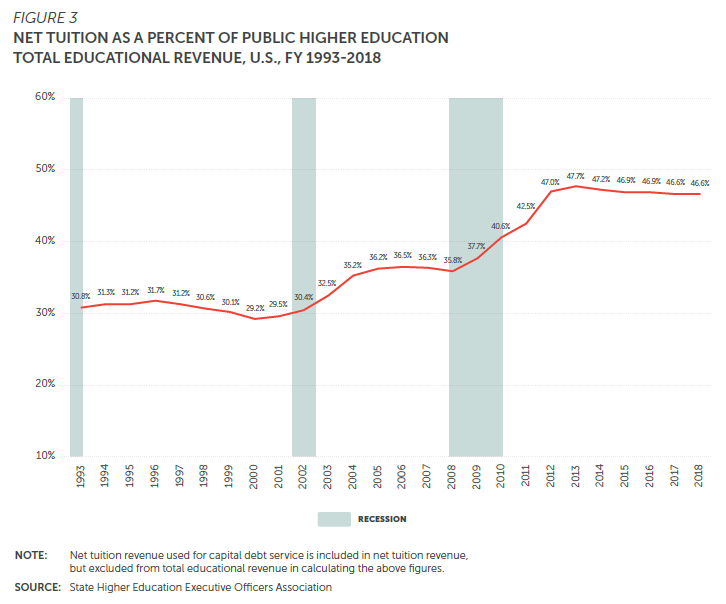

As in last year's study, researchers found that public higher education systems now rely more than ever on funding from students and families. More than half of states last year looked to tuition to a greater extent than they did taxpayer-supported appropriations.

In all, 27 states now rely on tuition for more than 50 percent of their public college revenue, down from 28 last year, according to the new report.

The phenomenon took hold recently and hadn’t been seen before the recession, said Sophia Laderman, a senior policy analyst with SHEEO. The degree to which states rely on tuition changes drastically state to state: it’s just 17.5 percent of total educational revenue in Wyoming, but in Vermont, net tuition represents 87 percent of total revenue.

The new findings focus on the 2018 fiscal year, which for most states ran from July 1, 2017, through June 30, 2018.

On average, states reduced appropriations by $2,000 per student during the recession. They’ve since raised them by about $1,000, on average. “We’ve halfway made up those cuts,” Laderman said.

As for net tuition, across the U.S. it now represents 46.6 percent of total educational revenue across public systems, essentially unchanged from 2017. Robert E. Anderson, SHEEO’s president, called it a “new norm” for state higher education funding.

During the recession, tuition as a share of revenue “kind of skyrocketed, increasing 10 percentage points in just a few years,” said Laderman. “This has historically been what states do when there’s a recession.” While state higher education appropriations are now slowly rising, she said reliance on tuition doesn’t bode well for the near future. “We’re concerned about what will happen during the next recession.”

The phenomenon also undercuts efforts to make college more affordable and accessible, said Kim Hunter Reed, Louisiana’s commissioner of higher education. “At a time that we have said that it [higher education] is a necessity, not a luxury, we are pricing education as a luxury.”

Net tuition revenue was actually flat in 2018, likely due to factors such as lower international enrollment, smaller tuition rate increases and increases in state public financial aid, the report found.

Enrollment declined in 35 states and the District of Columbia -- enrollment is 6 percent below the high in 2011 -- but the annual rate of enrollment decline in most states has slowed in each year since 2015. Nationally, 2018 saw a small (0.3 percent) decrease in full-time enrollment from 2017, but enrollment remains 7.1 percent above what it was before the recession.

In New Mexico, which has seen some of the nation’s largest declines in enrollment, Kate O’Neill, secretary of the New Mexico Higher Education Department, said part of the downturn -- especially in community colleges -- is attributable to an improving employment landscape.

Between 2016 and 2018, enrollment declined by 10.3 percent, or nearly 10,000 students. In the same period, the state saw a two-percentage-point drop in unemployment.

The state is now pushing to get most 3- and 4-year olds into prekindergarten, which translates into a need for public colleges to produce an estimated 350 new pre-K teachers over two or three years.

“We’re looking at scaling up every education program in the state,” O’Neill said.

In Louisiana, which had one of the largest declines in funding since the recession, Reed, the state higher ed commissioner, said several years of “stable funding” haven’t made up for “one of the worst disinvestments in the nation” during the recession.

“We’re concerned that we’re working against our goal of making sure that education is as affordable and equitable and accessible for all of our students,” she said.

Reed, who on Monday was preparing to begin the state’s new legislative session, said Laderman’s fears about the next recession are real to Louisiana families. “We can’t price ourselves out” of consideration for most families, she said. “We feel like we are at that point already.”