You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

University presses periodically face threats to the financial support they receive from their universities. Such support is crucial, leaders of academic publishing say, because university presses publish work with scholarly significance, knowing that impact must be measured in ideas shared or conventional wisdom challenged, not commercial standards on book sales.

But even if such threats occur periodically, many academics were stunned and angry to learn that Stanford University has announced that it will no longer provide any financial support for its press. Professors at Stanford are pushing back, but there are no signs that the university will reconsider.

Without support from the university, dozens of books released by the press each year would no longer be published.

“At first glance the proposition that a university of Stanford’s stature would voluntarily inflict damage upon an asset like the Stanford University Press seems shockingly improbable. The press is a world-class scholarly publisher with a 125-plus-year history -- a global ambassador of the university’s brand,” said Peter Berkery, executive director of the Association of University Presses, via email.

“It appears the Stanford administration is proceeding from the misperception that university presses are self-funding -- which, with only a handful of highly circumstantial exceptions, is demonstrably not the case.”

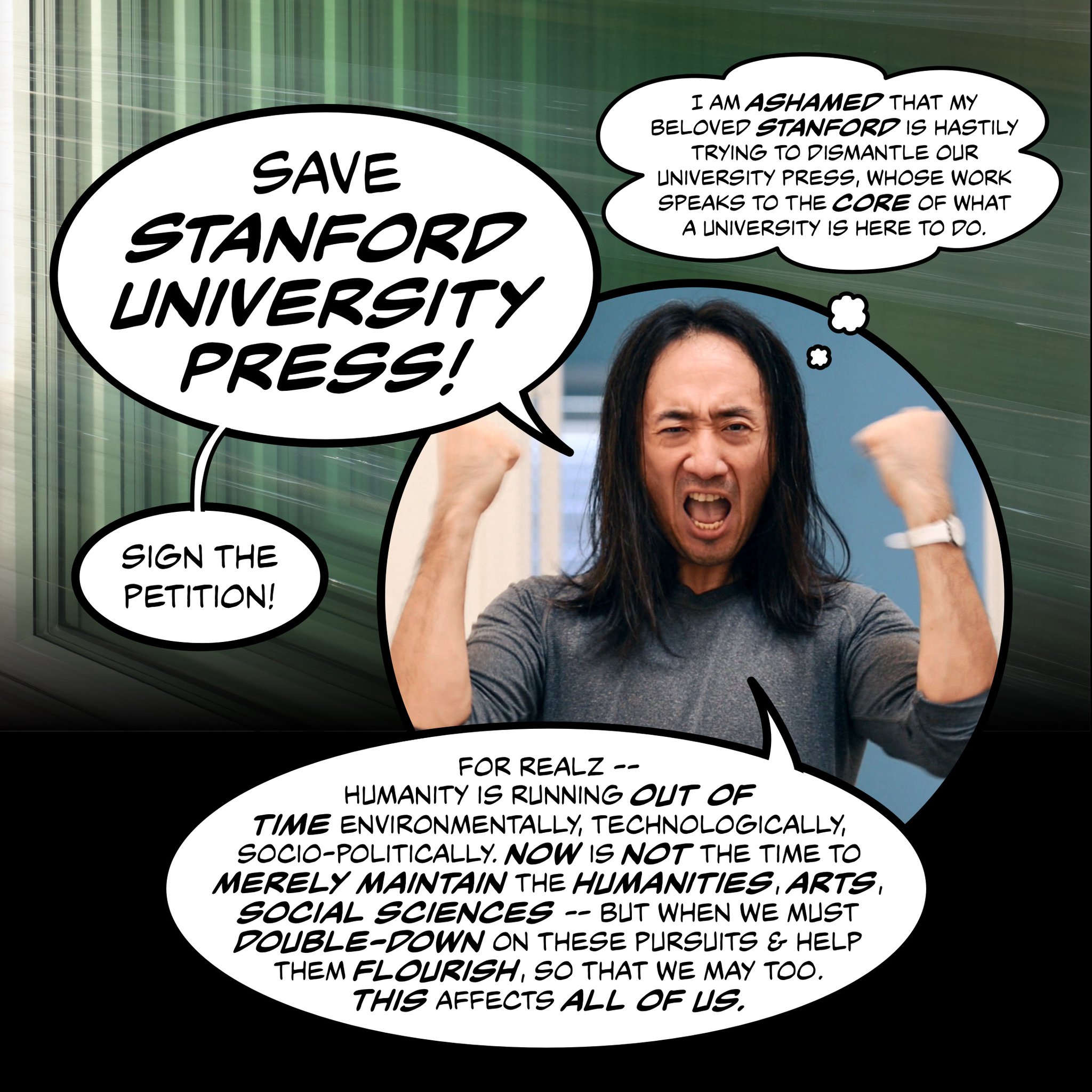

Ge Wang, an associate professor of music at Stanford, is circulating online both the illustration below and a petition opposing the changes. The image is adapted from one in a book by Wang, published by Stanford University Press, Artful Design: Technology in Search of the Sublime. "If we use a purely financial metric to assess the value of academic books, the scholarly mission of the academy will be lost. Presses will publish only profitable books, graduate students will write only profitable dissertations, and tenure will be awarded based on scholarship that is profitable," the petition says.

The Stanford press actually brings in about $5 million a year in book sales, a sum that is impressive compared to sales of many scholarly publishers. But it has also depended on support from the university, which in recent years has provided $1.7 million annually.

The Stanford press actually brings in about $5 million a year in book sales, a sum that is impressive compared to sales of many scholarly publishers. But it has also depended on support from the university, which in recent years has provided $1.7 million annually.

Provost Persis Drell told the Faculty Senate Thursday that the university was ending that funding. She cited a tight budget ahead, due to a smaller than anticipated payout coming from the endowment. (The endowment is worth more than $26 billion and is the fourth largest in American higher education.)

Drell told a group of faculty leaders recently that she considered the press “second rate” and that many of its series could be pruned, according to some present at the meeting. The comments angered many professors who consider the press to be a point of pride. A Stanford spokesman declined to comment on the reports that the provost called the press “second rate,” or to elaborate on her comments to the Faculty Senate.

Alan Harvey, director of the press, declined to comment.

Stanford publishes about 130 books a year. It is particularly well-known in the fields of Middle Eastern studies, Jewish studies, business, literature and philosophy. The press has also been capable of undertaking long-term scholarly efforts, such as a 20-year project to translate the Zohar, the key work in understanding the Jewish thought of the Kabbalah.

While much of the scholarship published by the press comes in traditional formats, the press has also been a leader in disseminating "born digital" scholarship.

Professors on the editorial board of the press have written to Drell and to President Marc Tessier-Lavigne objecting to the plans to end university financial support for the press. They noted that even though they are charged by Stanford with providing guidance on the press, and know more about the operations of the press than do most other professors at the university, they were not consulted about the idea of cutting the university subsidy.

Shrinking the press would be “a devastating statement” about the university’s priorities, the letter said.

Law professors have also circulated a protest letter, noting that many of them have published with the press. The law professors also asked why faculty members were not involved in the decision to make cuts.

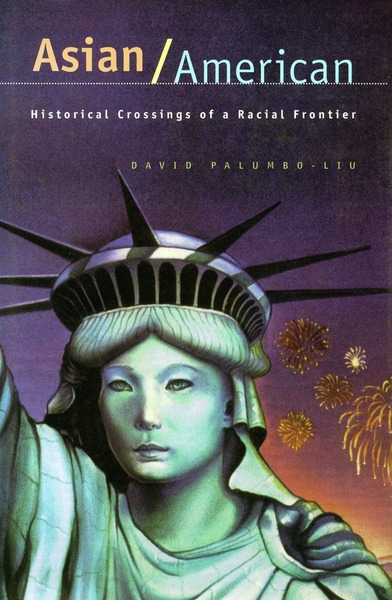

David Palumbo-Liu, a professor of comparative literature at Stanford, has published books with several university presses. Among the works he has published with Stanford University Press are The Poetics of Appropriation: The Literary Theory and Practice of Huang Tingjian, 1045-1105 and Asian/American: Historical Crossings of a Racial Frontier.

David Palumbo-Liu, a professor of comparative literature at Stanford, has published books with several university presses. Among the works he has published with Stanford University Press are The Poetics of Appropriation: The Literary Theory and Practice of Huang Tingjian, 1045-1105 and Asian/American: Historical Crossings of a Racial Frontier.

Via email, he said, “If these cuts go through, it will be a terrible day for not only Stanford, but for higher education as a whole -- it sends a signal that other institutions may well exploit. It is irresponsible and shameful. University presses perform both an institutional and a public good. They should not be judged by an economic calculus but by intellectual value and value to the intellectual life and reputation of the university.”

Palumbo-Liu added that the decision says something about what is valued at Stanford. University presses, he said, “should be considered a necessary expense and for an enormously wealthy school like Stanford to say it cannot afford $1.7 million to support its press is an embarrassing declaration of our lack of values. University presses, and the books they provide the global community, form an indispensable part of free speech and free inquiry, unconstrained by financial or political considerations. University presses are our equivalent of a free press.”

Gregory Britton, editorial director of the Johns Hopkins University Press, said a few presses have revenue streams beyond book sales and university endowments. Hopkins has Project Muse, for example.

“Those that look profitable often have substantial endowments, key intellectual properties (like assessment tools), distribution services or large journals programs supporting their books programs,” he said. Hopkins has Muse and many journals, but most presses don’t have the equivalent, he said.

Evaluating a press based on profitability, he said, misses the point of the mission of academic publishing. What university presses do, Britton said “is an extension of the mission of a university, and integral to how scholars share their work.”

He said that the decision at Stanford “seems deeply wrongheaded.”