You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

American workers are driven to pursue additional education, but they are looking to employers and the government to cover the college price tag, a new report revealed.

In its "Racial Differences on the Future of Work" survey, released Wednesday, the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, a think tank that focuses on African Americans, found that financial constraints are the primary barrier preventing American workers of all races from pursuing additional job training or higher education.

The survey, which oversampled and identified 1,500 black, Latino and Asian American respondents, showed about half of workers of color are interested in pursuing community college and certification and degree programs, compared to about 41 percent of white workers. The Joint Center surveyed U.S. adults of working age and included only employed adults' answers to questions related to respondents' jobs.

“One message to educators is -- they have a product that people want. The big question is accessibility,” said Spencer Overton, president of the Joint Center and a law professor at George Washington University. “People want … to attain skills so they can be a part of this new economy.”

However, a majority of survey respondents, even those considered high income, were not willing to personally invest more than $2,000 per year for additional job training and education that could advance their careers. The average tuition and fees for one year of college in 2018-19 was $3,660 for public two-year institutions, $10,230 for public four-year institutions and $35,830 for private four-year institutions, according to the College Board.

Workers are reluctant to invest in higher education and job training, unsure whether the return will be worth the capital it requires, Overton said. Though now, more and more positions expect workers go beyond their GED.

Workers are reluctant to invest in higher education and job training, unsure whether the return will be worth the capital it requires, Overton said. Though now, more and more positions expect workers go beyond their GED.

Increased automation also has led to less demand for low-skill workers, pushing more to pursue additional education. African Americans and Latinos are more concentrated in occupations vulnerable to replacement by technology, like retail and food preparation, according to a December 2017 Joint Center report on the economic consequences of technological innovation.

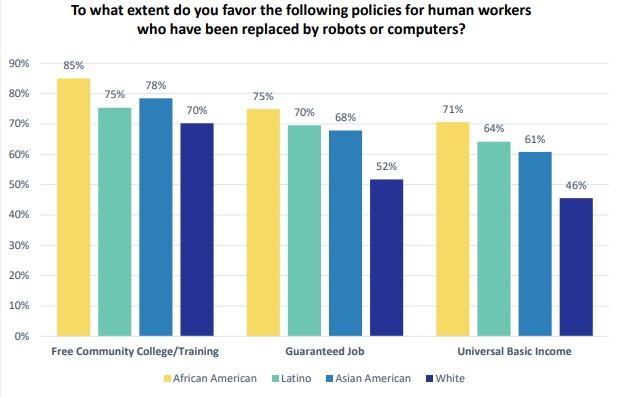

But in order to offset job loss to automation, minority groups expressed more desire than whites for the government to provide free college and other financial support.

An overwhelming number of minority respondents of both high and low income levels supported government solutions for workers who are displaced by automation. Eighty-five percent of African American respondents, 74 percent of Latinos and 77 percent of Asian Americans who make more than $75,000 annually favored tuition-free community college as a response to job displacement, versus 67 percent of whites at the same income level.

About two times as many respondents to the "Future of Work" study put the onus of preparing the American work force on the federal government rather than state governments, some of which have created free community college programs. Most states are having difficulty determining how to pay for them, said Harin Contractor, the Joint Center’s work-force policy director and co-author of the study.

“African Americans have more confidence in the federal government to take care of this,” Overton said.

While free community college was generally popular across the board, other government-provided solutions, including a federal jobs guarantee and universal basic income, had significantly lower levels of support from white respondents in the Joint Center’s 37-page study. This could be because minority groups have relied more on the federal government to provide financial support in the past, said Contractor, and they expect it in this era of technological change as well.

Contractor spent three years with the Obama administration as economic policy adviser to former Secretary of Labor Tom Perez, where he said the department worked on guiding young people of color into after-school and summer jobs that would present pathways to college.

“This demand for upskilling is critically important for communities of color,” Contractor said. “Policies to address the coming nature of the changing nature of work -- overwhelmingly, people of color want some policy responses from the government on this.”

It was especially important for the Joint Center to focus on communities of color because the shifting economy will disproportionately impact these communities, Overton said. The "Future of Work" survey is one of the first reports that analyzes how minority groups perceive their and their children’s future stake in the American economy and career outcomes, he said.

“People of color are estimated to become the majority of the United States population by sometime between 2040 and 2050,” the Joint Center report said. “Therefore, the perspectives of people of color today about technology, job readiness, employability, the acquisition of skills, benefits and education for children are even more critical to understanding the future of work.”

Minority groups also may be more interested in further education and training than whites because they have historically lacked these opportunities, Overton said. Even with community college or some college education in their backgrounds, minorities have the same work outcomes as less educated whites, Contractor said, suggesting it will take more than increased investment in education to close the achievement gap between racial groups.

“We really need to invest in human capital,” Overton said. “It can't just be low wages, some tax breaks and we'll have jobs. We’ve got to actually invest in people in terms of education, and also in terms of skills. If we don't, a lot of the racial disparities that we’ve seen in the past [are] going to be replicated.”