You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

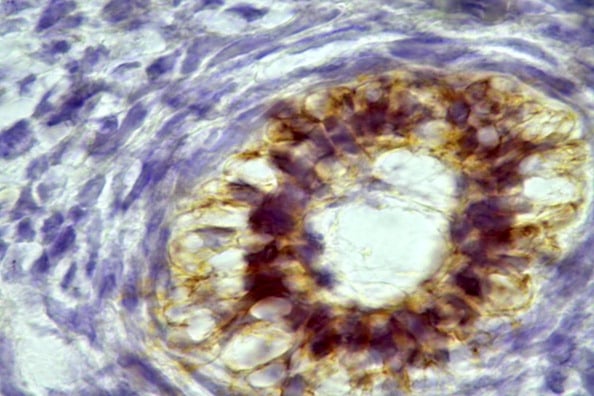

Getty Images

Researchers using fetal tissue faced another setback during the Trump administration as a notice from the National Institutes of Health spelled out new requirements for requesting grants for research involving the use of the tissue.

The NIH requirements are the newest in a number of barriers created by the Trump administration for fetal tissue researchers. Last month, the administration said it would bar scientists at federal agencies from conducting research using fetal tissue from elective abortions.

According to the NIH, those seeking grants for research that would utilize fetal tissue from abortions must, in a detailed manner, explain why no alternative methods could be used to accomplish the research. The new requirements will also ban graduate and postdoctoral students receiving NIH training funds from using fetal tissue in research.

Growing restrictions of this nature have been the result of successful campaigns of antiabortion proponents and groups that have lobbied the Trump administration. Fetal tissues are used by researchers to seek effective therapies for a variety of different diseases and illnesses.

“In addition to the detrimental impact this will have on medical research, these new restrictions highlight the unfortunate trend of politicizing medicine and research. We have seen the same trend with climate change and vaccines,” said Carolyn Coyne, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. “My concerns relate to more general concerns I have regarding our government and elected officials -- do they really want to protect human health or do they want to be re-elected?”

Larry Goldstein, a University of California, San Diego, professor of cellular and molecular medicine as well as the director of the UC San Diego Stem Cell Program, said one of the difficulties created by these requirements is in the details of how a grant proposal will have to be made. Goldstein said the justification for the use of fetal tissue, as part of the new requirements, will be included in the “research strategy and approach” section of the application, which has page limitations.

“You’ll have to actually shrink the science part of your application to make room for the fetal tissue part,” Goldstein said. “And I think the fetal tissue part won’t be as well justified because of the page limits.”

Goldstein said in typical NIH applications, there’s a separate section for justifying the use of human or animal subjects in research, which is not typically page limited so one can thoroughly justify the use. Goldstein said the fetal tissue justification would be better served in that section of the application.

Applications will go through a review from ethics advisory boards at NIH, which are still in the process of being formed. Goldstein said it’s unclear what the makeup of those boards will be, and he hopes they won’t be a place where “good applications go to die” but instead where proposals are considered on a scientific basis. Goldstein also said he was concerned that researchers who make discoveries in the field of stem cell research who need fetal tissue to compare the results with will have to write a completely new proposal.

“It’s a very redundant process,” Goldstein said. “It really sets the bar high on investigators who made some discovery who need a quick check of fetal tissue -- [they] will write a new proposal and go through a competitive review, which is always a dodgy business.”

Coyne said she believed this redundant process was created to intentionally stymie any potential research involving fetal tissue.

“Many of these new restrictions are clearly intended to make the procedural aspect of fetal tissue research so cumbersome as to discourage researchers from engaging in this research,” Coyne said. “While some of the new restrictions are an outright ban, I suspect others have been made intentionally arduous.”

Both Coyne and Goldstein said these continued hurdles in the field will have a lasting effect on scientific advancement and lead to greater setbacks.

“The new policy forbids all fetal tissue research in any training-type award granted by the NIH,” Coyne said. “This extends to predoctoral students, postdoctoral fellows, clinical fellows and those in training who wish to be funded for transition awards, which are viewed by some as a great strength in faculty applications. Certainly research itself will be delayed, but perhaps more concerning is the impact on our current generation of young scientists, who may be irreversibly damaged by these policies.”