You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The nearly monthlong drama surrounding the Alaska governor's decision to slash 41 percent from the state's allocation to the University of Alaska system has been widely portrayed as a battle between Governor Mike Dunleavy and those who support the university.

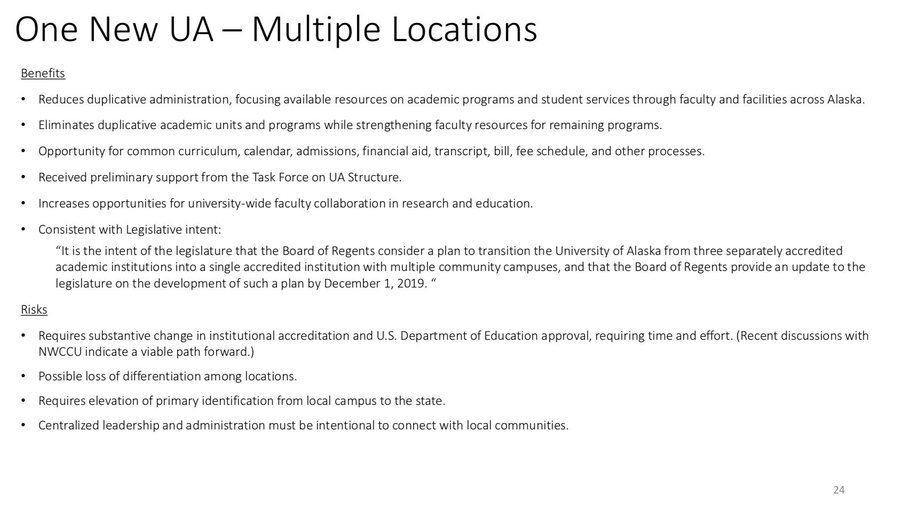

But seven hours of discussion and debate by the university's Board of Regents revealed a significant chasm between the university's supporters, too. Although the divided governing board ultimately voted 8 to 3 to support President Jim Johnsen's recommendation to move toward a singly accredited university, it did so over the objections of chancellors of the university's three main campuses and many faculty and student leaders who argued instead for maintaining three separately accredited institutions.

To a person, the members of the board and all those who spoke before it unequivocally believe the planned $136 million cut in state funds will damage the university. Johnsen called the reduction "truly existential," precipitating an "unprecedented fiscal crisis in magnitude and speed."

The board's chairman, John Davies, stated the obvious when he said, "The premise that we need to be cut by $135 million is something we don't agree with." Discussing one particular potential victim of the cut, the university's museum, Davies said that the cultural institution would be "easy to destroy" even though it "took 75 years to create it." Many others involved in the discussion made similar references to the dangers of swift decision making about such important matters.

But Alaska's university leaders have been left little choice by the governor, who addressed the board by telephone midway through Tuesday's meeting. He opened his remarks with praise for the university and its role in Alaska's economy and culture, noting that he is a graduate and that his two daughters have studied there, too.

His comments were barbed, though. The university has "been the beneficiary over the years" of strong funding from the state, Dunleavy said, and those who don't recognize that today is different are "still living in the belief that we have $85- to $95-a-barrel oil." It is time for the university, like all state entities, to pay more attention to student outcomes and "have a real look in the mirror, which we all should … to see if we can do better."

Dunleavy noted that last Friday, he had softened his proposed immediate cut of $136 million in the current 2019-20 fiscal year in favor of a "step-down" approach that would spread the cuts over two years, with about $90 million this year and $40 million in 2020-21. But the offer came with a major catch: the cuts would have to come in "categories" of the state leader's choosing.

That potential delay aside, the governor (and a representative from his Office of Management and Budget who spoke at length during the meeting) offered little hope of any serious rollback of the cuts, even though legislators have sought to restore some of the funding.

Facing the inevitability of major cuts, much of the day's sometimes emotional conversation focused on how best to bring about required reductions.

It's the board's responsibility to decide, President Johnsen said in framing the day's discussion, "whether the house is on fire or whether it's just toast burning." As he laid it out, board members who believed the financial crisis is less severe can afford to take a more modest and less urgent approach.

"My view is that the house is on fire," he said, arguing that the reality of scarcer resources required a dramatic restructuring like the one he said he had come to favor, in which the campuses would unite as "one university."

The chancellors of the three campuses, which have long been accused of competing and challenging each other more than cooperating, were given the chance to present their own vision, which was at odds with Johnsen's.

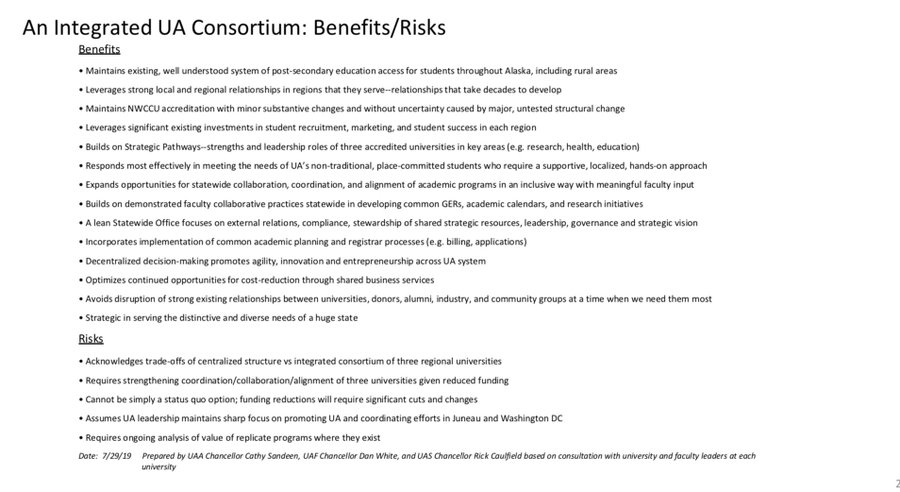

Under the plan they had developed, which they described as an "integrated UA consortium," the three universities would each make a series of significant cuts on their own and then work much more closely together to build off each other's strengths and supplement their weaknesses.

"Going to a single accreditation has significant downsides," said Rick Caulfield, chancellor of the University of Alaska Southeast, by far the smallest of the three campuses. The chancellors' proposal, by contrast, would "address the immediate needs for cuts, to address the fire that's in our house, but not throw out the distinctive qualities of the three accredited universities."

The differing views of the system president and the campus chancellors is not distinctive to Alaska; many recent debates over funding and governance in public higher education have ultimately devolved into battles of wills between system leaders who argue for greater centralization and campus administrators who do not. (It's not incidental that the three chancellors' plan called for a "lean statewide office" focused on a narrower set of responsibilities and puts more decision making closer to "consumers," as Cathy Sandeen, chancellor of Alaska's largest campus in Anchorage, put it.)

"Our model retains more direct contact and less bureaucracy," she said.

Sandeen also made the case that the chancellors' approach would result in the least amount of "drastic structural change" made on the fly.

Some regents were skeptical of the campus leaders' promise of increased collaboration. Dale Anderson said the regents had tried many times in the past to get the Alaska campuses to cooperate.

“Why is this all of a sudden at the forefront?” he asked. “This must have been a real, excuse the term, come-to-Jesus meeting that you guys have had … We have tried and tried and tried to get cooperation between the campuses, and it is nonexistent. I am looking at your comments with a pretty jaundiced eye.”

The debate continued for several hours more, well past the original end point of the meeting, with regents weighing varying proposals as tensions mounted and divisions grew sharper (though, being Alaskans, the participants remained civil).

The motion the board ultimately approved -- whose author read it between emotional pauses and amid tears -- calls on Johnsen to prepare a plan for board approval "for transitioning to single accreditation," in consultation with faculty, staff and student leaders, and in the meantime for campus constituents to reduce back-office administrative costs and eliminate duplicative academic programs and schools.

"This is not the end of the road," said Davies, the board chair. "It's the beginning of a discussion."