You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

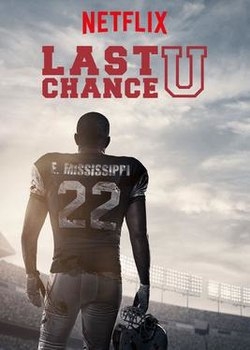

Netflix

Brett Vana, the new athletics director at Independence Community College, stayed up until 3 a.m. answering emails last Wednesday.

On this particular night, he was answering a slew of questions from staff members after writing several recommendation letters for former athletes from the college.

With just three weeks on the job, he spends his nights catching up on administrative details and his days running around the campus in Independence, Kan., a town of about 10,000 people, lots of cornfields, a single high school and little notoriety -- until two years ago.

That's when camera crews from Netflix swooped in and thrust the college and the town into a searing national spotlight with the production company's documentary series Last Chance U. The series is a behind-the-scenes chronicle of the ups and downs of low-profile, two-year college football programs and the attempts by the institutions to propel the athletes to programs at four-year institutions or even on to professional teams.

Though the show gave the college exposure, it also set off a series of events that bruised the town's reputation and led to multiple departures of high-level administrators, including the president.

Vana is too busy doing damage control on and off campus to think about the new season of Last Chance U, which begins in 2020. He’s “righting the ship,” he says during an early-morning phone interview, sounding worn down from lack of sleep. He is supervising practices, arranging schedules and meeting with townsfolk who feel wronged by the portrayal of their close-knit community as a podunk town with little going for it except the community college -- specifically, its football team.

Most of the college officials featured in the third and fourth seasons of the series, which was focused on Independence and aired in 2018 and 2019, are gone now. Their departures were part of the stunning fallout that resulted from the team's star turn on the small screen. The former athletics director left and got a new job with the Kansas City public school system. The college’s president resigned.

None of these former officials were as controversial as Jason Brown, the potbellied, profanity-spouting "bull in a china shop," as he was described in the series. In the first three minutes of the first episode of the fourth season, Brown is shown walking into an auditorium filled with players and proclaiming abruptly, “All right, motherfuckers, shut up.”

The stories of these players, many of whom were depicted as having their last shot at college football glory, were compelling. There was the quarterback whose father died in a tragic car accident and the linebacker who almost went to jail for alleged robbery but lucked out when the charges were dropped due to lack of evidence. But Brown was the show’s reality TV breakout star -- an unfiltered personality, fueled by testosterone and competitiveness, who berated players for poor grades, shrieked in their faces and belittled them with nicknames such as “slapdicks.”

The cameras loved him.

Brown left the college after local newspaper reporters wrote about how he sent a text to a team player, who is German, that read, “I’m your new Hitler now.”

The Montgomery County Attorney’s Office later charged Brown with eight felonies -- four counts of identity theft and four counts of blackmail -- after he allegedly sent fake cease-and-desist letters to newspapers that wrote articles critical of him. Brown had posed as a lawyer from the Cochran Firm, which is famous for defending O. J. Simpson in his murder case.

College administrators and town folks are glad Independence's regrettable brush with fame is finally behind them. Last Chance U is now some other college's problem. That college would be Laney College in Oakland, Calif., which will be the subject of the fifth season of Last Chance U and is scheduled to air sometime next year.

While some people are wondering if the same fate will befall Laney, critics of the series are still asking if the fame and money Independence got from the show was worth the trade-off of its now battered image.

A Laney spokeswoman did not respond to repeated interview requests.

Last Chance U's debut season followed the East Mississippi Community College Lions during the team’s 2015 season. It was hailed by sportswriters as one the first filmed attempts to capture with some openness and grit the life of a two-year-college football player. But there is a marked difference in how much more access coach Brown granted film crews than East Mississippi allowed, said Kiyoshi Harris, who was formerly an associate football coach at Independence but was elevated to the top job after Brown’s exit.

Brown allowed filming of players on the field, in the locker rooms and in dormitories on a near-constant basis, Harris said. He and other officials at Independence agree that Brown was the force behind getting Last Chance U to come to Independence in the first place. The show’s producers and directors considered three other institutions, but in Brown they found a candid -- and often brash -- figure that attracted viewers.

Despite the sometimes negative impression the show gave of Independence and the surrounding area, the college was rewarded. It secured a lucrative $250,000 contract with Adidas, which helped outfit the team and coaches with slick cleats and other gear, Harris said. Independence was able to capitalize on publicity from the show and sell athletics merchandise that branded it as “Dream U,” a college where players’ fantasies of football fame could be realized.

Football was always of interest to the larger town, but many more donors and boosters emerged and contributed to the college as the popularity of the series grew and gained national attention, Harris said. Tourists came to see the town, which was good for local businesses, he said.

The first season at Independence seemed to Harris to be more natural, focusing on young men who loved football. Brown and the team dominated the 2017 football season, helping win the Kansas Jayhawk Community College Conference for the first time since 1987. The fourth season opens with Brown ruminating about possible national titles and brimming with confidence that the team would reach even loftier heights.

It did not. The team went a dismal 2-8. Though Harris said the program essentially had its pick of talented football recruits after the first season aired, many of the players chose Independence "for the wrong reasons" -- just to be on the show. They didn't necessarily want to play well, Harris said.

By the 2018 season, more than 80 percent of the team was from outside Kansas. This is unusual, because community colleges are generally oriented to serving students who live in the same areas where the colleges are located.

George C. Knox, the new interim president at Independence, blamed the influx of out-of-state students on a decision by the conference in 2016 to remove a cap on the number of out-of-state players who could be on a team and on scholarship.

Harris didn’t always agree with the show’s portrayal of the town, either. He noted it’s not necessarily as small as the show made it seem, and not everyone was obsessed with football.

“There’s a lot of hardworking people just living a great life out here,” said Harris, whom Brown lured to Independence after he taught high school for nearly two decades and coached junior college football in Southern California.

Athletics department staffers and new leaders of the college, such as Knox, are now adamant that sports don’t take priority over academics, as the show seemed to suggest. This was not always the case. The former president, Daniel Barwick, who announced he would step down in June, was a well-known advocate of the football program, sometimes to the detriment of other departments.

For instance, the budget for football remained relatively intact while other academic departments saw their funding slashed in previous academic years. The institution’s operating budget is about $12 million this academic year.

News reports indicate Barwick also was key in bringing in Last Chance U to the campus.

Independence had also been put on notice in 2017 by its accreditor, the Higher Learning Commission, for potentially keeping poor records and not planning strategically. The accreditor later flagged possible “ethical lapses” related to athletes allegedly being told that attending classes was not important and their grades would be “taken care of.” Administrators refuted this and other accusations.

Knox, who previously was the executive director for the Council on Accreditation for Two-Year Colleges and president of Labette Community College, also in Kansas, said he couldn’t address the allegations. Although Knox had never watched Last Chance U before coming to Independence, he said the profanity Brown spewed bothered him.

Knox said he's now focused on fixing what hadn’t been “properly budgeted,” such as paying for bus rentals for away games. Knox said that with all the attention placed on football, the college's budget and other affairs were partially neglected and in disarray. When he first arrived, he had 17 officials reporting directly to him. Now he has five.

“The national exposure was wonderful, but in my mind, I see some things I would have done differently,” he said.

Knox is trying to clean up the image of the college. Hiring Vana, who proudly touts himself as a man of faith, was part of that effort.

Vana said he is inspired to help ailing institutions because his grandmother ran a recreation center that catered to troubled youth in inner-city Cleveland. He also wants to “raise the bar on academic standards” for the college's athletes and has asked coaches to set a minimum grade point average for athletes between 2.75 and 3.0.

“This is a tremendous place that had a lot of misguided leadership,” Vana said.

Christopher Parker, president and chief executive officer of the National Junior College Athletic Association, which represents the 60,000 athletes at two-year institutions, believes the entire premise of Last Chance U may have been misguided. He thinks the show has only one redeeming quality: it's a conversation starter about athletics at two-year colleges. Beyond that, he says, the series has no value.

Last Chance U presents the institutions it profiles as poorly run, poorly funded and located in communities that consider football their saving grace. But for many athletes, two-year programs are not the last chance. Athletics are part of the college experience at many two-year institutions, but the academics are obviously what help students reach their goals of attending four-year colleges, Parker said. The National Collegiate Athletic Association recently released statistics that show nearly 25 percent of baseball players in Division I colleges first attended an NJCAA institution.

The producers of Last Chance U met with Parker and other NJCAA leaders six months ago because they "wanted to change the story angle," Parker said.

It was too late, he said. By then, two-year institutions were turning away the show because of how it depicted East Mississippi and Independence.

Parker wouldn't speculate why Laney agreed to participate.

But despite the drawbacks, he said, Last Chance U does put institutions on the map.

"It's an opportunity for exposure," Parker said.