You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

University of Alabama's campus in Tuscaloosa

University of Alabama

Only the relatively wealthiest students can afford to attend most public flagship institutions, according to a new report released last week by the Institute for Higher Education Policy.

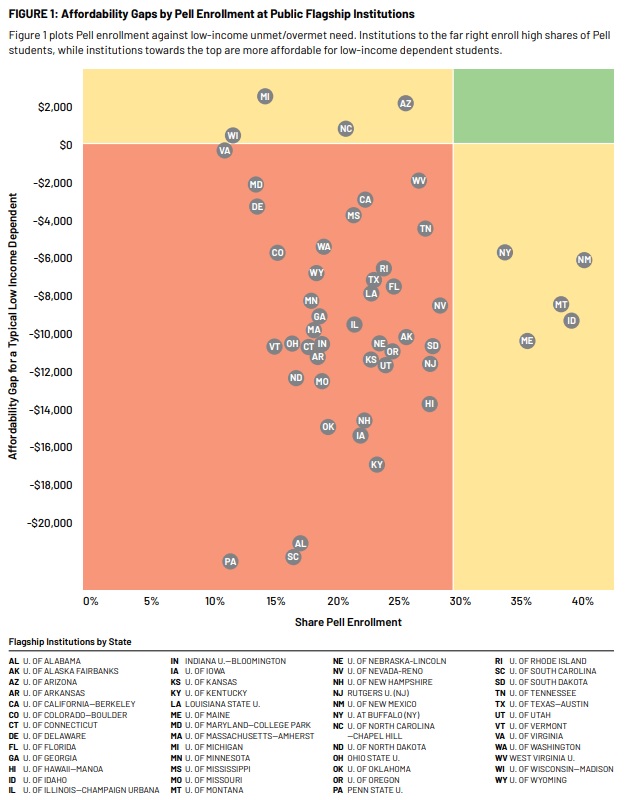

The report found that only six of 50 state flagships meet an affordability benchmark for low-income students (see graphic, below).

Mamie Voight, vice president of policy research at IHEP and a co-author of the report, said public institutions funded by taxpayers should better serve low-income students, a demographic that's growing in overall college enrollments. Flagship universities often have high graduation rates and good post-college outcomes for students, Voight said, making them a good vehicle for social mobility.

But flagships "are not following through on that promise," she said, because they aren't providing affordable, accessible education for low- and middle-income students. This results in some students taking out large loans, working long hours while attending school and facing difficulty covering basic needs such as food, all of which can lead to poorer outcomes for the students. Other students may opt for a less expensive college with fewer supports, or forgo college altogether.

The report created five profiles of students using nationally representative data. They include three dependent students who are low-income, middle-income and high-income; and two independent students, one with dependents and one without dependents.

To determine what each student could afford to pay, the report used the "Rule of 10" benchmark from the Lumina Foundation, which says that a family should be able to pay college costs by setting aside 10 percent of discretionary income for 10 years, with the student working 10 hours per week while enrolled.

Using these metrics, the profiled high-income student can afford to attend any state flagship in the country, with money left over. At six flagships, aid awarded to the high-income student could fully pay for the unmet need of the low-income student.

This is due to "poor aid prioritization," the report states.

"The decisions that leaders are making in terms of spending really comes down to prioritization of different values and different priorities," Voight said, adding that some schools may try to attract more high-income students to boost prestige, while others may target aid to increase equity.

The University of Alabama is a prime example of poor prioritization, according to the report. In the analysis, the low-income student has an annual unmet need of $20,000 to cover costs, while the need of the high-income student is exceeded by nearly $16,000.

"We are like many other institutions that are trying to find that right balance," said Kevin Whitaker, provost for academic affairs at the University of Alabama. "We are trying to provide scholarship programs for students, and I think we have a very robust scholarship program that benefits a lot of students."

Whitaker said the university has a spectrum of scholarships available to students, some of which consider financial need and some of which do not. He said a "buffet" of options is necessary because students are different. And Whitaker disagrees that scholarships should be targeted solely at students with financial need.

"There are students that, when they qualify for a merit scholarship, have worked very, very hard," he said. "And to somehow reduce their efforts simply because of their financial place, it just seems wrong to me."

Voight, however, doesn't agree that prioritizing scholarships to low- and middle-income students would penalize high-income students.

"They have resources to pay for college," she said, while "too many low-income students are being priced out of higher education because of those financial aid dollars not being made available to them."

Whitaker said the university is taking steps to address gaps with programs like the newly released Alabama Advantage program, which covers in-state tuition for federal Pell Grant recipients after factoring in other scholarships and grants. Students need to enroll full-time and maintain a GPA of at least 2.0 to qualify.

The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill is one of the six flagships the study found to be affordable for low-income students. It's also affordable for independent students with dependents, and nearly affordable for independent students without dependents. While it's not affordable for middle-income students, the amount of unmet need for those students is relatively small ($3,523) compared to other flagships.

Rachelle Feldman, associate provost and director of scholarships and student aid at the university, said Chapel Hill's affordability is due to its culture.

"The campus is very committed to its public nature," Feldman said. The annual cost of attendance is $23,734, and the Carolina Covenant program at the university commits to meeting the full needs of students whose families' incomes are below 200 percent of the poverty line.

"Our campus would be worse off without these students," she said.

The program covers items beyond tuition, like room and board, books and healthcare if the student requires it. The university relies on private funding and fundraising efforts, as well as state and federal aid, to keep the program running, Feldman said, though she noted it's a challenge.

The report also highlights the academic and personal support -- like mentoring, social events and business etiquette -- that is offered to students in the program, which Feldman said is a "key part."

Thirteen percent of undergraduates at the university are part of the Covenant program. Those with financial need had a six-year graduation rate for the 2012 cohort of 88.7 percent, slightly below those without financial need in the same cohort, who had a six-year graduation rate of 91.5 percent.

However, enrollment of federal Pell Grant recipients at the university is low compared to the national average of "very selective" four-year institutions. That average is 30 percent, while the campus has a Pell enrollment rate of 21 percent.

Feldman said the university is "need-blind" in the admissions process, but it has goals to increase its Pell enrollment rate over time through outreach with various programs like the Carolina College Advising Corps, which places recent graduates as college advisers in certain high schools.

Voight said increasing equity is the responsibility of both institutions and states. Most states' funding for public higher education has yet to rebound from the Great Recession, which triggered tuition hikes and reliance on out-of-state or international students to balance budgets.

Whitaker said the University of Alabama's low Pell enrollment rate (roughly 17 percent) is probably a result of the institution's focus on out-of-state recruiting. The college is now "correcting" that trend with the Alabama Advantage program, he said.

To make a full correction, Voight said universities need to look at their decisions on how to spend aid funds, states need to increase funding levels and the federal investment in Pell Grants needs to increase. Flagships also need to examine admissions policies, like early decision and legacy preference, to ensure equitable access for low-income students.

"We hope that institutions will take a look at these findings with respect to both affordability and accessibility and … reexamine themselves through an equity lens," she said.