You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

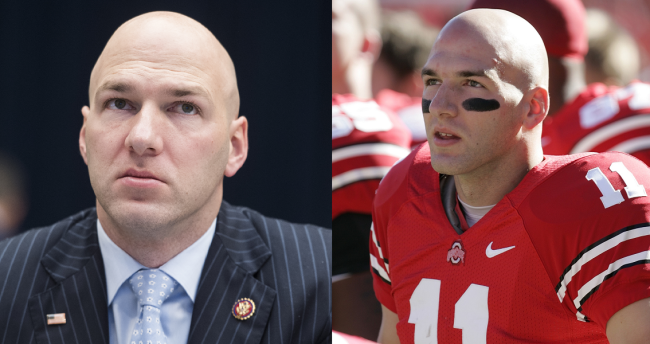

U.S. representative Anthony Gonzalez, now and then

Getty Images

The country's largest state has thrown its legislative weight behind letting college athletes profit from their status -- and now more than a dozen states and Congress may follow California's lead. The spreading movement adds to the mounting pressure on the National Collegiate Athletic Association to improve its treatment of big-time college athletes.

U.S. representative Anthony Gonzalez, a Republican from Ohio, announced a plan to introduce a federal bill similar to the California legislation on the House floor, which could alter how the NCAA responds to the California law. The association said in May that players in California -- including in the Pac-12, arguably the most successful Division I conference in the nation -- would be disqualified from competition if they receive compensation for their name, image and likeness, as the state law now permits.

Gonzalez, a former Ohio State University football player, told ESPN that he would want to work on a quicker timeline than the California law, which takes effect in 2023. But he plans to wait to bring his bill forward until later this month, when the NCAA's working group examining the association’s rules around name, image and likeness delivers a report to the group's leadership, ESPN reported.

“The current California law is not workable due to its state-by-state approach,” Gonzalez said in a statement. “We need one national solution that provides safeguards for college athletes while ensuring they are able to receive income off their name, image and likeness.”

The California law, Senate Bill 206, nicknamed Fair Pay to Play, prevents the NCAA from disqualifying collegiate players if they have third-party contracts with vendors that pay them for marketing campaigns, sponsorships and other uses of their name and image. It does not allow college athletes to be paid by their university, which was a strategic move by California legislators to propel the bill further, said Callan Stein, a partner at the law firm Pepper Hamilton who works in white-collar legislation and follows NCAA issues in the courts.

“The California law was very smartly drafted -- it was more narrow in scope than prior attempts to address the NCAA amateur issue,” Stein said. “The bill doesn’t seek to name athletes employees of the schools; they don’t get salaries from the school. They don’t devalue the NCAA scholarship and room and board … It really just prevents the schools from stripping players of payments.”

Several state legislators -- including in Florida, Minnesota, Nevada, Pennsylvania and South Carolina -- have announced they plan to introduce legislation similar to the California bill, and Kevin Parker, a state senator from New York, introduced a bill in September that is currently in committee.

While momentum for additional compensation for college players appears to be building, don't overestimate it; the NCAA and the college sports establishment have withstood such pressures before. Earlier this decade, the Supreme Court declined to hear O’Bannon v. NCAA, upholding the NCAA’s amateurism standard, despite opinions opposing the standard in federal court. And efforts to allow athletes to unionize gained traction with the National Labor Relations Board before hitting a wall.

The NCAA has tweaked but not overhauled its rules on amateurism in the face of those and other pressures. Charles Clotfelter, a professor of economics at Duke University and author of Big-Time Sports in American Universities, was a skeptic of change in the NCAA in the past and said he remains skeptical despite legislative movement.

"I’m pretty sure they’re going to fight this, because it goes to a core value for the NCAA, and the value is stated as, the purity of athletics is best protected by the traditional concept of amateurism, and amateurism is inconsistent with getting paid," Clotfelter said.

Gonzalez's bill is also not the first time college athlete compensation has reached Congress; another bill in support of paying college athletes has sat in the House of Representatives since March, failing to gain much attention.

U.S. representative Mark Walker, a Republican from North Carolina, introduced the Student Athlete Equality Act, which proposes the NCAA’s tax-exempt status be revoked if it does not allow players to be paid by third parties. The bill currently sits in the House Ways and Means Committee, and Stein said it’s less attractive than the proposed Gonzalez bill, which aims to work with the NCAA to adjust federal law and its own rules, rather than penalize the association.

There are hints that the NCAA would consider changes if it’s being pushed nationally. In a statement on Monday, the association said, “Improvement needs to happen on a national level through the NCAA’s rules-making process,” and “a patchwork of different laws from different states” would not work for maintaining a “level playing field” for all NCAA member institutions.

A spokesperson for the NCAA wrote in an email that the association stands by its Monday statement and did not comment further on national legislation.

Walter Harrison, a former president of the University of Hartford who chaired the NCAA’s Board of Governors (then called the Executive Committee) from 2004 to 2007, said before now, he can’t recall the association reaching a moment where it needed to choose between changing its own bylaws or risking governments taking legislative action to make changes. State and federal lawmakers also do not understand the ins and outs of college athletics, as the NCAA does, he said.

“It would be a very bad precedent to cede regulation of college athletics to government,” Harrison said. “I don’t think government regulation helps at all -- it would muddy up the waters … The NCAA is not very nimble, but the government is even less nimble.”

In its initial response to the California legislation in May, the NCAA suggested that the bill would be unconstitutional, and the association was probably suggesting that the law would violate interstate commerce, Stein said. The federal government has oversight of commercial exchanges that span multiple states, according to the U.S. Constitution.

“If a federal bill is to be passed, that argument would disappear,” Stein said.

A Seton Hall Sports poll released Thursday found that 60 percent of 714 respondents endorsed allowing college athletes to be paid. Stein said that if this view holds for the public at large, it could be an easy, bipartisan effort in Congress.

However, the main concern with the California bill is there are no safeguards established to protect players from nefarious talent agents, recruiters or corporations who could use athletes’ contracts to their own benefit, Harrison said. With more money to be made on an individual level, athletes could be taken advantage of, he said.

“I’ve seen too many agents -- when they aren’t even allowed to do this -- screwing around with college athletes’ lives,” said Harrison, who served as Hartford’s president for nearly 20 years. “[Agents could offer], ‘if you transfer schools, I’d be able to get you some money, get you looked at by the NBA.’ That sort of thing … would destroy college athletics, and more importantly destroy these young peoples’ lives.”

Men’s basketball and football players, whose sports are the most popular for media and merchandise deals, would also be the primary beneficiaries of Fair Pay to Play, said Harrison, who wondered what detrimental effect the legislation could have on women’s sports, or less attended collegiate sports programs, especially at smaller universities.

"We’re talking about a pretty small number of college athletes whose value is so outsized," Clotfelter said. "If an economist were to look at this situation, by and large, college athletes don’t have all that much market value, but a few of them have a tremendous amount … what do you do about this gross imbalance?"

Any predictions on what the NCAA will do next are pure speculation, Stein said, and the college athletics world will have to patiently wait until later in October, when the association’s working group on name, image and likeness is set to deliver recommendations.