You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images / Anadolu Agency

College students from high-income families are responsible for some of the most drastic borrowing increases seen in recent decades, according to a new report that raises questions about exactly whose concerns are fueling talk of a student debt crisis.

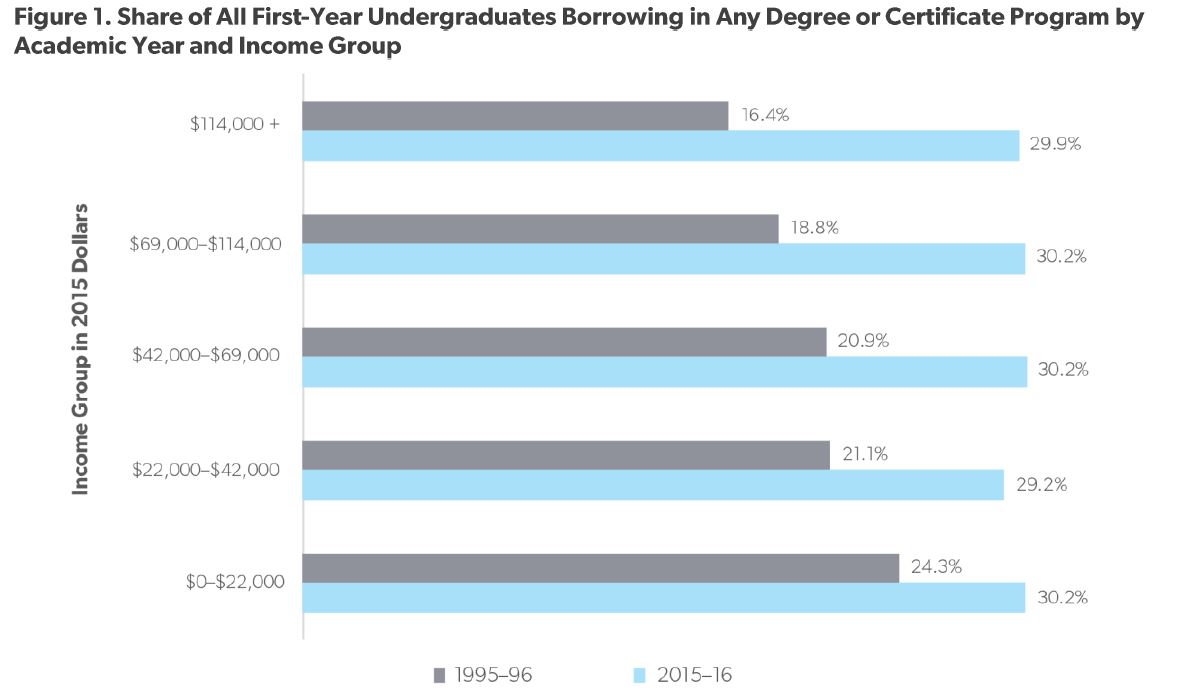

In 1995-96, just 16.4 percent of first-year undergraduates from families making an inflation-adjusted income of more than $114,000 took out student loans. That compares to 24.3 percent of those from families making $22,000 or less who borrowed, according to the report.

But by 2015-16, borrowing rates were nearly identical across all income groups -- right around 30 percent.

Amounts borrowed climbed faster for students from high-income families as well, said the report, from the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank.

The findings don’t indicate those from families of means hold the majority of the country’s $1.5 trillion student loan debt. Students from high-income backgrounds still hold less total debt than other students, in part because they are a relatively small share of total college enrollment.

Nor does the report suggest students from high-income backgrounds are more likely to have trouble paying back student loans than those from low-income families. The report is intended to highlight changes in borrowing that may be ignored in other conversations, said its author, Jason Delisle.

“I’m sort of agnostic about how much is too much debt and what’s the right amount, at least for this sort of exercise,” said Delisle, a resident fellow at AEI. “Sometimes it’s good to get back to these sorts of basic statistics about who is borrowing and how much that’s changed.”

Still, students from high-income families have student loan debts making up a “disproportionately large share of the total amount borrowed,” Delisle found. That fact invites further discussion about who stands to benefit most from different proposals to forgive student loan debt or other potential policy changes to federal financial aid programs.

It also prompted Delisle to ask why student debt has gained traction as a political issue at this particular moment in time.

“I do think a lot of the anxiety that fuels the conversation is sort of upper-income driven,” Delisle said. “I don’t think it’s a coincidence that about the time everyone decided there was a student debt crisis, it coincided with middle- and upper-middle- and high-income families -- the majority of them -- turning to student debt.”

Liberal commentators didn’t directly dispute the idea that the wealthy could be helping to drive the narrative, although they reacted to the report by saying it also showed high debt levels for poor students. Student loans hitting “middle-income families over a 20-year period” might explain their political salience at the moment, Mark Huelsman, associate director for policy and research at the liberal think tank Demos, said in an email.

“But I’d like for us to keep our eye on the ball here a bit: the percent of low-income students borrowing for a bachelor’s degree is unconscionably high, particularly if you consider their debt loads as a percent of their family income and wealth,” Huelsman wrote. “Even if low-income students and high-income students were borrowing the exact same amount for college, that debt is a far greater burden relative to their family wealth.”

Delisle’s report examines borrowers’ characteristics when student loans were originated. In doing so, it seeks to evaluate student lending from a different perspective than others who have looked at borrowers who are repaying their loans.

It analyzes borrowing patterns among students using data from the U.S. Department of Education’s National Postsecondary Student Aid Study. The report examines the share of students who took on debt and the amount they borrowed by family income quintile. Two different points in students’ college careers were studied: first-year undergraduates and students who completed bachelor’s degrees.

Debts incurred by students in graduate or professional programs were not included. That’s a key point, because such loans made up about 40 percent of outstanding student loan debt. Delisle adjusted figures for inflation to 2015 dollars.

Borrowing Changes Over Time

In the 1995-96 academic year, 16.4 percent of first-year undergraduates from families making more than $114,000 borrowed. Two decades later, 29.9 percent did, meaning borrowing in the group increased by 13.5 percentage points over two decades.

The gap in borrowing rates between the two points in time shrinks with each step down the family income ladder -- it’s 11.4 percentage points for those making $69,000 to $114,000, 9.3 percentage points for those making $42,000 to $69,000, and so on. Still, more students in every income bracket borrowed in 2015-16 than did so in 1995-96.

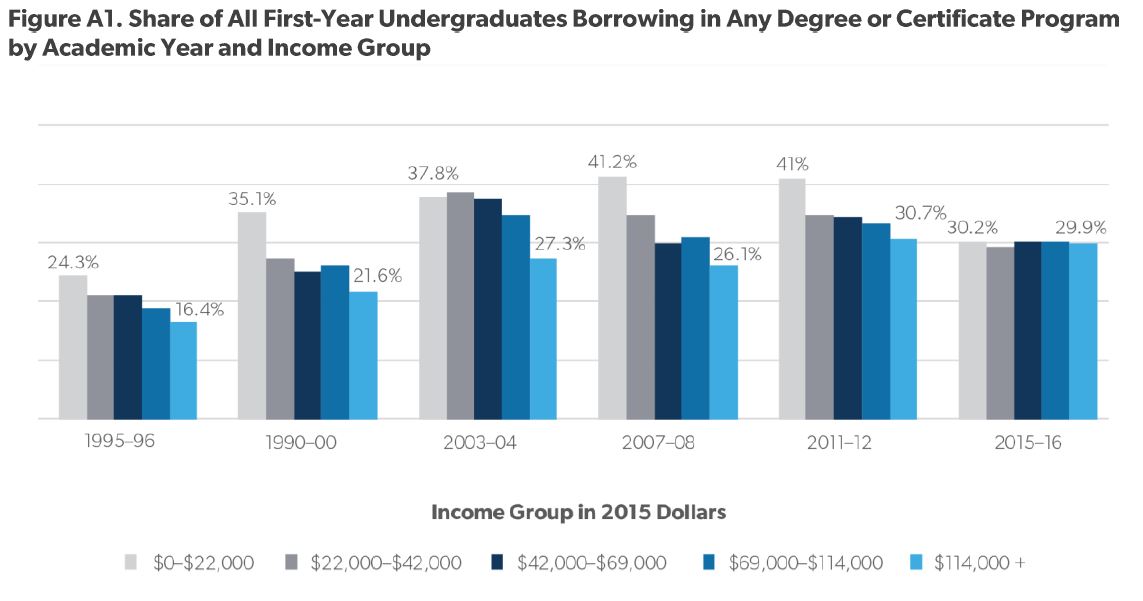

If the calendar were turned back to 2011-12, the findings would be very different, however. That year, 41 percent of students from the lowest income bracket borrowed, meaning borrowing rates dropped substantially in the next four years.

Had that decline not taken place, borrowing rates would have increased by the greatest amount among low-income students -- not high-income students -- over the last two decades. “In other words,” the report says, “the popular view that low-income students have turned to debt more than other groups was correct up until recently.”

Experts in student debt did not expect to see the recent plunge in borrowing rates for low-income students.

“The sharp drop in the share of low-income students borrowing in 2015-16 is quite surprising and deserves more examination before basing a lot of conclusions on it,” Sandy Baum, a nonresident senior fellow at the Urban Institute, said in an email.

Until more data is available, it’s not possible to determine if a new trend in borrowing patterns is developing or if 2015-16 was an anomaly. Delisle could only offer theories about why borrowing rates declined among low-income students.

Possible reasons include changes in student demographics as adult and returning students who enrolled in college when job openings were scarce because of the Great Recession started deciding to enter the workforce. Some student aid programs might also be doing a better job of helping students avoid debt, Delisle suggested. And students from low-income families may have grown warier of debt than they were in the past.

It’s not clear whether the change in borrowing rates would be beneficial if it were to hold in future years.

“I don’t know if that’s necessarily a good or bad thing,” Delisle said. “For some people, I’m sure it’s good. For some, it’s a bad thing if the loans might help them finish or take more classes.”

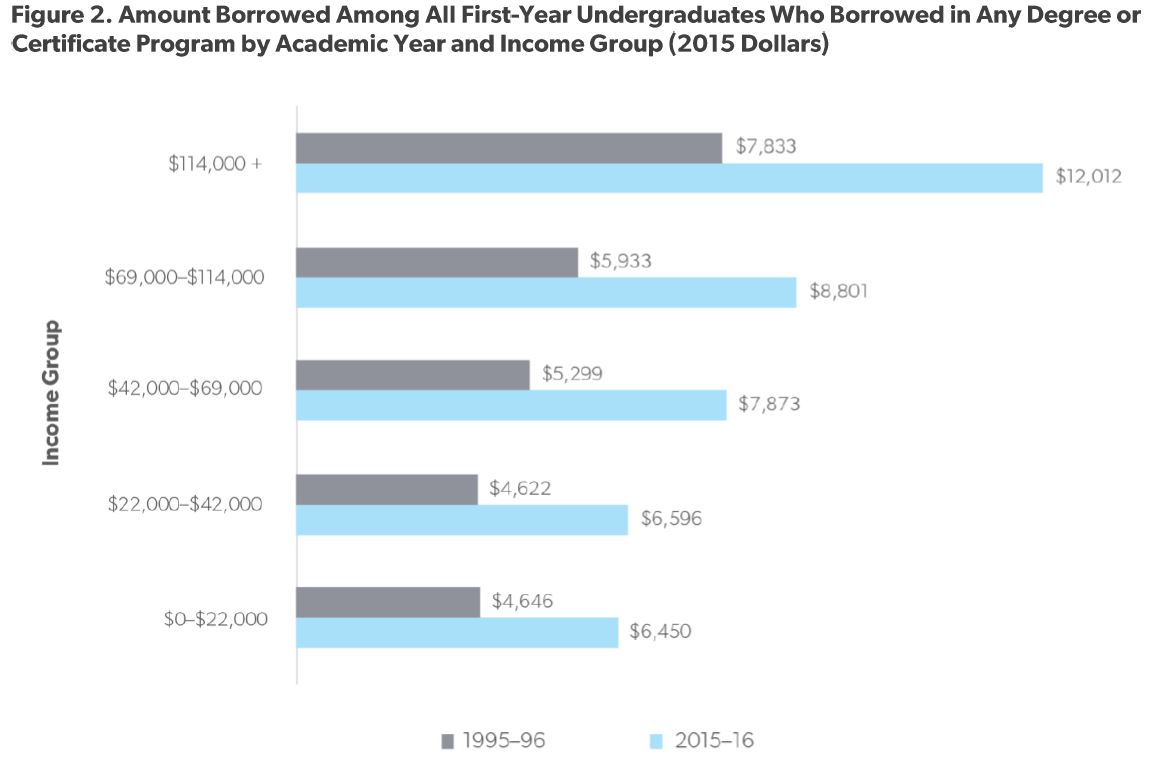

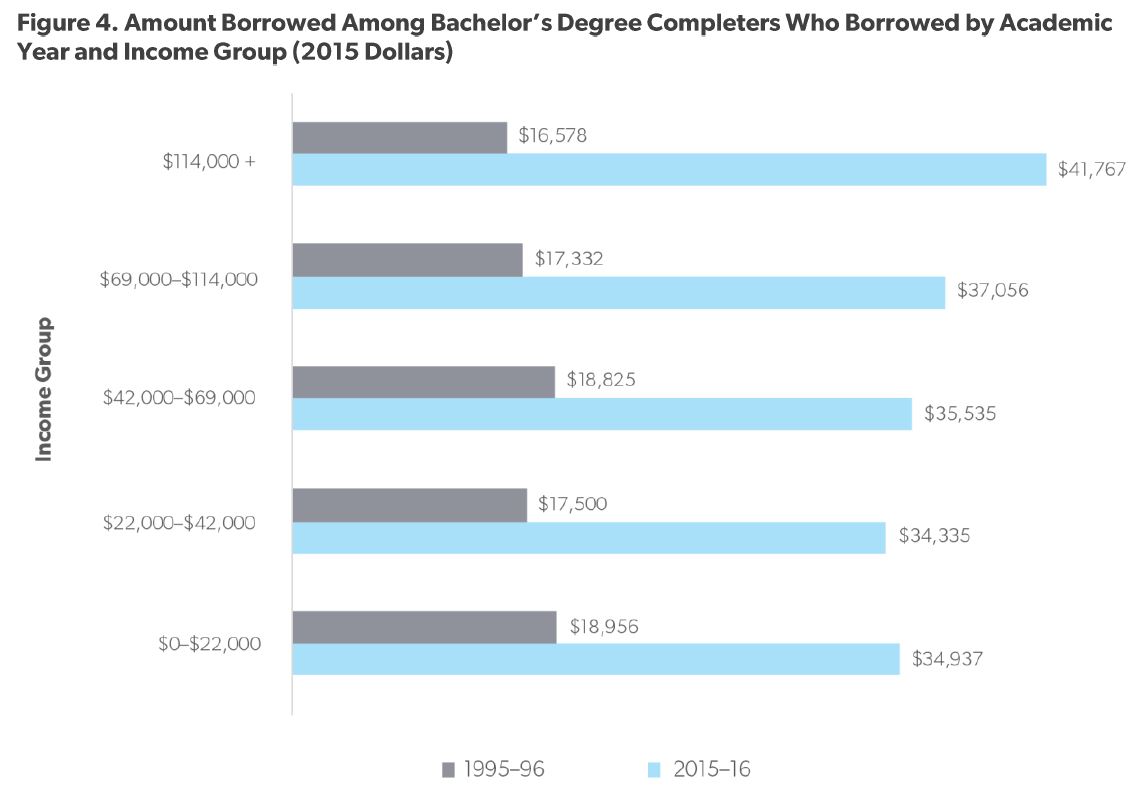

Among those who did take out loans, amounts borrowed rose across all income groups between 1995-96 and 2015-16. Again, though, the largest changes unfolded for students from the highest-earning families.

Students in the highest quintile borrowed about $4,000 more in 2015-16 than they did in 1995-96. Those from the bottom two quintiles borrowed about $2,000 more.

In part, this is due to where high-income students enroll and what they study. They are more likely to enroll in four-year bachelor’s programs, the report said. And they are more likely to enroll at pricey private institutions.

Low-income students, on the other hand, are more likely to enroll in programs awarding certificates or associate’s degrees and at lower-priced public institutions.

The recent developments have skewed undergraduate debt more toward higher-income households than it has been in the past. In the mid-1990s, students from the top income quintile took out about 10 percent of the debt borrowed by first-year undergraduates, the report said. By 2015-16, they borrowed almost 18 percent.

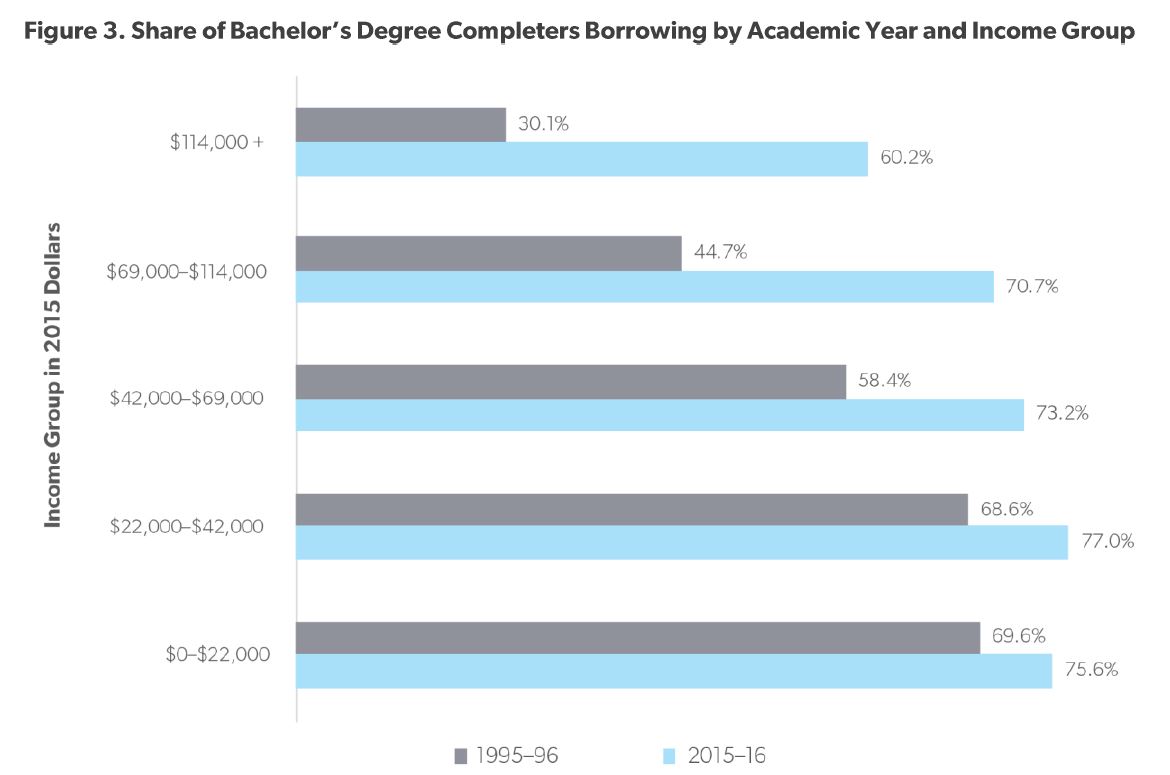

Borrowing patterns of students who completed bachelor’s degrees in 1995-96 and in 2015-16 showed that those from the lowest two income quintiles only became slightly more likely to borrow over that time frame, on a relative basis. Those from families earning $22,000 or less in 1995-96 borrowed 69.6 percent of the time, compared to 75.6 percent in 2015-16.

On the other hand, the percentage of students from the highest income group who borrowed doubled over the same time frame. It rose from 30.1 percent to 60.2 percent.

Cumulative debt for completers climbed substantially over the two decades studied. Average debt loads “roughly doubled regardless of income, except the highest income group,” the report said. Debt in that highest income group grew even more, going from borrowing the lowest amount to the most. The average completer from a high-income family borrowed $16,578 in 1995-96 but $41,767 in 2015-16.

A factor driving the different rates of increases over time could be that the top quintile is experiencing large tuition increases or that such students are choosing to attend more expensive institutions, the report said. Average net tuition and fees for students from the top income group -- after subtracting grants and scholarships -- jumped by $4,400 between 1995-96 and 2015-16 to $13,604. That’s about twice as much as the increase for students in the other income groups.

“They’re paying more for tuition,” Delisle said. “The other thing, for the universities, is that price discrimination is getting more intense. They’re charging those students more with high sticker prices and pushing some of the aid down to lower-income students.”

Price discrimination, or tuition discounting, is a practice that has been on the rise for years at colleges and universities that seek to use financial aid to enroll student bodies that meet various enrollment needs.

Baum, of the Urban Institute, suggested another factor that could be driving borrowing. Student loans might have become easier to obtain than other types of debt.

“It is reasonable to believe that at least some of the increase in this borrowing is the result of the increased difficulty of obtaining home equity loans,” she said. “We don’t have the data to verify this, but that phenomenon could explain some of the increase in borrowing among students from more affluent households.”

Another issue to consider is that the data in the AEI report don’t include debt incurred by those who didn’t complete degrees.

“It is clear that people who stay in school longer borrow more than others -- and students from more affluent backgrounds are more likely to stay in school to earn bachelor’s degrees,” Baum wrote.

It’s one of the reasons Delisle spent time looking at changes in borrowing among first-year undergraduates.

“This is why I wanted to do the first-year-only slice,” he said. “We capture everybody -- the whole undergraduate picture, regardless of degree and regardless of whether or not you go on to finish.”